Meeting the women – the ‘Girls’ – shaking up the keirin velodrome in Japan.

by Matthew Holmes

To non-cycling fans, the world of keirin could be quite a mystery, especially as their first exposure is often the baffling sight of Olympic riders filing after a mystery man on a motorised bike, lapping the velodrome and silently increasing speed seemingly oblivious to the fact they are not even winning.

After that, though, when the pace rider slips off the track, some of the greatest skills in professional cycling are on display; riders conserve energy by seeking out the slipstream of the rider in front – leaving at times millimetres between their wheels and those of the rider in front at well over 50 km/h, going round a slope angled at 43 degrees – before impeccably timing their charge for the line, smashing their legs onto the pedals and arching their back for a final few millimetres of advantage at the finish.

Here in Japan, the velodrome, which was home to much local heroism at the London Olympics (Brits Victoria Pendleton and Chris Hoy both took gold in the Olympic keirin) seems to be home to a phenomenon that goes beyond sport. And it’s going through some changes.

Just what is keirin racing?

Keirin, the word literally means ‘racing wheels’, was started in Japan in 1948 by the NJS, the Nihon Jitensha Shinkokai (which roughly translates as the Japan Bicycle Promotion Association), in part to help repair broken communities and move the industry forward after the second world war.

Ticket sales and gambling takings have made it into big business, with around 800 billion yen taken each year, and though far from its heyday in the 1980s, this unique part of Japanese culture is something of an institution which goes deeper than its relatively young age would suggest.

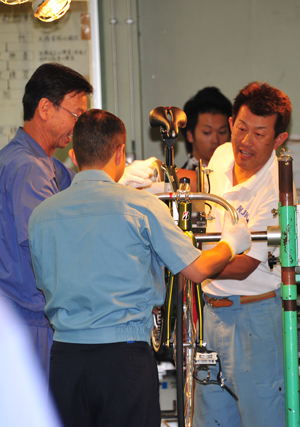

Traditionally, all the bicycles are the same, frames are made of steel and each part is stamped with approval for meeting NJS regulations. This is a level playing field; riders must train relentlessly to improve their rankings and there is great mutual respect.

Backstage at the races on a scorching August evening, with my phone confiscated as per the strict, almost military rules for all, I saw riders meticulously cleaning, checking and polishing every millimetre of their own frames, chains and stays, taking the bikes apart and putting them back together, readying them for battle.

I saw intense warm ups on the treadmills; I smelled rubber on the floor and liniment on the muscles; I heard shouts of passion through the concentrated silence and I saw a final superstitious handful of salt thrown over one rider’s frame.

This is the domain of the dedicated.

Not all rosy for keirin

Gambling in Japan is a peculiar thing to many outside observers. Those of us who live here see pachinko parlours every day but we are told gambling is “illegal” – there are ways to skirt the law, clearly, and for cultural or historical reasons an exception seems to have been made. But three legitimate kōei kyōgi (public sports) exist at which gambling is definitely allowed: horse racing, powerboat racing, speedway and keirin.

“Our enterprise has a long, long history,” explains Tatsuakira Yamamoto of the Japan Keirin Association, “but recently our revenue has been going down.” The fan base is growing older: a typical trip to the velodrome, particularly on a weekday, involves, “perhaps more than 80% ojiisan (the older generation of guys)”

“Men’s keirin is rather focused on gambling and we have to change the the somewhat dirty image of that,” Yamamoto says, “So we need new fans, we have to find a new thing to appeal to the public, and that’s why we started Girl’s Keirin. Since July 1st, our first race, many younger guys have been coming down, enjoying a beer after work and watching the races – mostly under floodlights.”

Seeing the recent trend for and popularity of women’s sport in Japan – our conversation briefly strayed towards the affectionately named Nadeshiko, Japan’s women’s football team – I put it to Yamamoto that it seems that to move towards greater appeal, even by bringing women into the equation, people will have to see it as more of a ‘sport’ than a game to be gambled upon.

“Yeah, I think that’s right. So we changed the regulations and the rules a bit. Men’s keirin especially is made for guessing, for prediction. The rules are made so that it is really difficult to know who will come first.”

Riders form allegiances and “rough play” forms a big part of the final lap. “We have adopted the international standards and rules for the women, which don’t allow so much of that. It will make the riders focus on getting better, themselves. We hope that that, and the newer equipment, can ultimately help us send someone to (the) Rio (Olympics) in 2016.”

They are not ready yet but the professional riders, a diverse band of women ranging in age from 19 to 50 (the oldest rider, Miyoko Takamatsu, used to be a teacher) are getting better.

The athletes

How do you go about starting a sport afresh? First, you need athletes. Four years ago, the organisation looked at professional cyclists in Japan and realised there were too few of them. “We had to pick up athletes from other fields, such as ice skating or ice hockey,” Yamamoto explains, “Even track and field. And we approached the national associations of many sports, asking them to invite their athletes to apply.”

Why would they switch to keirin? Former professional badminton player, Miyoko Toda, 23, tells me that when she heard she was immediately enthusiastic.

“I was playing in the top league but I kind of felt that I had reached my ceiling. I had wanted to be a top pro-athlete since I was a kid and I knew this might be my last chance to really meet that challenge.”

Toda is smart, and talks honestly and passionately about her place in the ‘new’ sport. She doesn’t think the girls are simply a ‘gimmick’ for keirin, which she sees as “such a particularly Japanese thing, like a part of our culture.” She has colourful, alternately painted nails and laughs when our photographer suggests she might not want to be photographed post race, “what’s wrong with my hair?!”

On being one of the ‘faces’ of the sport – we are talking just half an hour after she qualified for a final at the Keiokaku Velodrome, near Chofu in western Tokyo – Toda says, “If kids, and women, if they see me and I give off a sporty image, I want that to attract them.”

“The entertainment is good (at the velodrome) and we look kind of fashionable. But I also want to appear sort of ‘kawaii’ (cute) – maybe people will enjoy that aspect!”

Toda is serious, too. “Every race we get better. I kind of quit badminton with unfinished business in the middle of my career, so this time I really want to push myself to the point I can work no more. So that I can be proud.”

What of the men?

Toda says they get on quite well and that behind the scenes there are jokes, and occasional glances towards her bike. The girls ride aerodynamic, carbon framed bicycles with tri-spoke ‘aero’ wheels at the front and they look much like world-class Olympic machines – with a splash more colour.

Toda is proud of her bicycle, “It’s so fast, so exciting to ride, even the guys sometimes say it ‘looks cool’.”

That might be an understatement. The bicycles would be equally at home under some of the “pisto people”, as Yamamoto calls them, who ride through Harajuku with fixed gear bikes tuned for the track but ridden for high fashion, often without brakes.

“Of course we, our bikes, have a connection with the messenger community, too (and NJS stamped bikes are worth three or four times their original value when sold in the US or Europe), but those guys, sometimes,” he laughs, “those guys are ‘too naughty’.”

Are the male riders jealous? Yamamoto explains that the top riders will always be superstars, idols of sorts. And the men definitely rule, but the success of Girl’s Keirin has been a surprise to some of them, he says.

“There are 33 professional women and around 3,000 men. Those top guys are not concerned but some of the lower ranked guys, I think they think [the women] are their menace.”

“We have riders who are gaining a lot of fans – former triathlete, Kanako Kase, who tops the prize money rankings so far with 1.8 m yen, has a kind of ‘bad girl’ image.” Yamamoto wants to create a kind of story, going through to the Grand Prix at the end of the year (scheduled for December 28).

“Actually, Kase and Yukari Nakamura, who is perhaps not as physical but tactically so good, will not race together until then, I hope. I want people to keep guessing who will win.”

The spirit of keirin

It seems almost impossible for the people I meet to explain or sum up the spirit of keirin and what drew them to it but though perhaps seen by many as fairly niche, it is getting attention around the world.

National cycling associations have shown an interest in taking both the ‘Girl’s’ and mens events to places such as Australia, Yamamoto says proudly – it is something of a passion of his and really his personal mission within the JKA. There have been challenges but things are starting to look up.

He is keen to stress at the end of our long conversation his message to the public: “At the moment, we don’t have a lot of English information for spectators at the velodrome but, the race itself, if you see the race, you will know.”

And Toda agrees, “You have seen it. You know. People should see it once, and if they do they will definitely feel good.”

Visit Girl’sKeirin.com (the apostrophe is theirs!) for more info (in Japanese)

We visited Keiokaku Velodrome, which is in Chofu, about 25 minutes from Shinjuku on the Keio line. The keirin Official Website has lots of useful information in English, including maps.

Many thanks to the JKA for supplying additional images and for helping arrange our race day and interview with Miyuko Toda.

All images copyright Weekender and JKA.

This piece originally appeared in our September 2012 issue. To see it as it was in the magazine, click here and ‘flip’ to page 14.

_KRAACH-クリスタルバスソルト-385x257.jpg)