Japan is producing more world-class ballerinas than ever before, yet is losing most of them to countries like Russia, England and France. We caught up with Ryoichi Hirano and Akane Takada, two of Japan’s most successful dancers on the international stage, to learn more about why there’s little incentive for aspiring professionals to remain here.

For Ryoichi Hirano and Akane Takada, the dream was always to perform at the London Royal Ballet, a feat achieved by both during their teens. The male and female pair has been mesmerizing audiences for quite a few seasons already, and this summer became the first Japanese dancers in more than two decades to be elevated to principals at the prestigious company.

The highest rank attainable for a ballerina, it’s a position currently held by a number of Japanese dancers around the world including Misa Kuranaga (Boston Ballet), Ako Kondo (Australian Ballet) and 2014 Benois de la Danse winner Mariko Kida (Royal Swedish Ballet). The success of these dancers has helped raise the profile of ballet in Japan and will no doubt encourage younger generations to take lessons in even greater numbers. On the downside, Japan continues to lose its most talented ballerinas to foreign establishments. It’s a trend that Ryoichi Hirano believes will continue into the foreseeable future.

“The life of a ballerina is not easy anywhere, but I think it’s particularly tough in Japan,” he tells Weekender from the Royal Opera House in Convent Garden, London. “You have many dancers making huge sacrifices to appear in shows not knowing whether they’re going to get paid. They don’t receive any protection as there are no regulations or unions in place. The fact is ballet dancing is seen more as a hobby and not classed as a real job. In the UK we’re treated as professionals who work under labor laws. Here at the Royal Ballet we’re properly looked after with masseurs, body experts, sports scientists, and so on. I know every company cannot be at that level, but right now the gap’s too big.”

“It’s a shame because there are lots of good things happening in Japanese ballet at the moment. Its popularity is increasing, schools are thriving and the success of so many dancers overseas shows the teaching methods are working. The problem is that there’s no central company binding everything together.”

The hope was that the National Ballet of Japan would become that company. Since opening in 1987, however, it’s struggled with funding. Financial aid is provided in the form of government subsidies, but it’s nothing like the kind of support European establishments receive. With almost all ballet companies operating at a loss, they rely on sponsorship in order to survive. A lack of money in Japan means dancers are usually paid on a commission basis, so if sales are bad they might not receive anything at all. The situation is much more secure for London-based dancer Akane Takada.

“British ballet is seen as being more than a form of art; from a cultural perspective it’s viewed as something that’s very important,” she says. “In Japan it’s different. Fans are fanatical and people will comment about how amazing the dances look, but it’ll probably never enjoy the kind of status that something like kabuki receives because it simply doesn’t have the history. That makes it more difficult to attract investors. It also has a reputation as a posh form of entertainment for elite members of society who all dress immaculately. In England you have customers coming in jeans and T-shirts all the time.”

One man trying to change that image is Tetsuya “Teddy” Kumakawa. Japan’s most famous ballerina, he was the last dancer from this country, before Takada and Hirano, to be elevated to a principal at the Royal Ballet back in 1993 (Miyako Yoshida became a principal two years later; however, she was recruited, not promoted). In 1998, Kumakawa made the surprising and controversial decision to quit the famed British company in order to set up a Japanese organization called K-Ballet. He brought five leading dancers with him, but it was undoubtedly his own reputation that helped secure sponsorship deals with a number of big corporations including the TV station TBS. Because of these partnerships, K-Ballet has been able to tour the country extensively, produce numerous shows overseas, and pay monthly wages to dancers ranging from the rank of principal to first artist.

“Ballet has become more mainstream in Japan and that’s mainly down to Teddy’s influence,” says Hirano. “He has appeared on many TV shows and that helps to attract new fans in an instant. His company has had a massive impact and is part of the reason why Akane and I have received so much interest from the media.”

This summer, Hirano and Takada were given a heroes’ welcome when they toured the country with the Royal Ballet, and were even afforded some time to speak with Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. The hope now is that their success, and the accomplishments of many other Japanese dancers overseas, will encourage the government and local businesses to invest more heavily in ballet.

“That’d be nice,” says Hirano. “When I was young I dreamed of dancing for the Royal Ballet in England. Hopefully in the future kids will have similar dreams about performing at a Japanese company. I think we’re a long way from being at that level yet, but as I mentioned there’s a lot to be positive about. If we can find that central stick to bind everything together then the future would look even brighter.”

Akane Takada

Tokyo-born dancer Akane Takada started ballet at the age of three, and by the time she reached elementary school, she had already decided her goal in life: To perform at the Royal Ballet like her idol Miyako Yoshida. “She was just so precise in her movements, it was amazing to watch.” Takada did more than just watch. She spent hours at the Hiromi Takahashi Ballet Studio perfecting moves she’d seen on VCR.

At 15 she moved to Russia to join the renowned Bolshoi Ballet Academy. Two years later she won the Audience Choice Award at the Prix de Lausanne and received a scholarship from the London Royal Ballet. Takada quickly worked her way up the ladder, winning successive promotions to first artist then soloist. A knee injury halted her progress for two seasons, but she came back strongly, becoming first soloist in 2014. This summer she reached the pinnacle of her profession when it was announced that she was to be elevated

to principal.

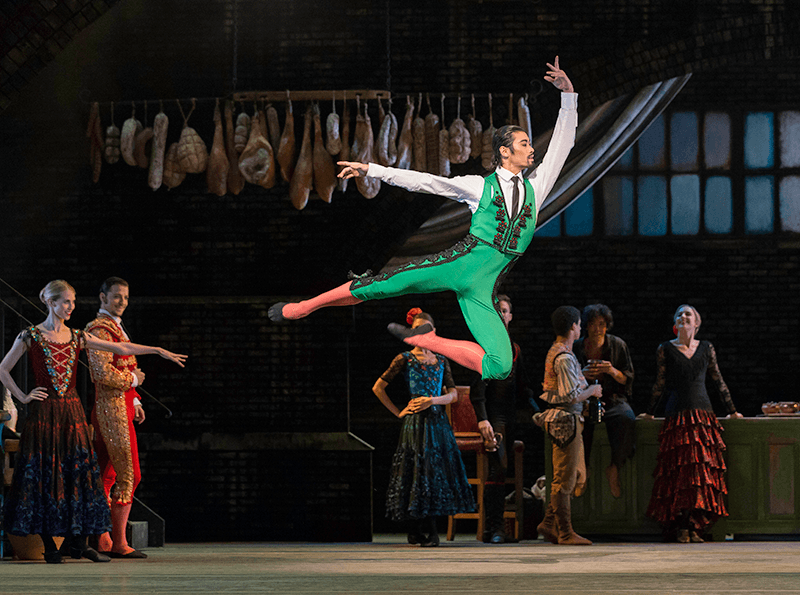

Ryoichi Hirano

For Ryoichi Hirano, the dream started at his mother’s ballet school in Osaka more than three decades ago. “My brother Keiichi had already joined and I was always turning up swinging from the rails, imitating other students,” he says. “It made sense to start taking classes.” Hirano didn’t have any specific heroes growing up, stating that he “just wanted to take the best bits from different dancers” he saw to try and “create something unique.” In 2001 he showed the world what he was capable of by winning a gold medal at the Prix de Lausanne, and he was drafted in by the Royal Ballet soon after. The elegant dancer gradually progressed through the ranks, becoming first soloist in 2012. Four years later at the age of 32 he achieved his ultimate ambition when he was named a principal dancer.

To watch Ryoichi Hirano and Akane Takada’s performances for the Royal Ballet via the Royal Opera House’s Live Cinema Season, visit http://tohotowa.co.jp/roh/

Main Image: ©ROH Photo by Tristram Kenton