I wonder why

the rain that falls from black clouds

shines like silver.

I wonder why

the silkworm that eats green mulberry leaves

is so white.

I wonder why

the moonflower that no one tends

blooms on its own.

I wonder why

everyone I ask

about these things

laughs and says, “That’s just how it is.”

(“Wonder”)

The young woman who posed these questions in verse was born on April 11, 114 years ago, in a small Yamaguchi Prefecture town called Senzaki, where the mainland extends a peninsula into the Sea of Japan that almost grazes an island called Omi. Her name – or the pen name by which she is best known – is Misuzu Kaneko.

Her life was short and tragic. Her father died when she was three, and she was raised by a single mother, who managed a bookstore in Senzaki. Misuzu married young, and her husband, who worked at the bookstore, betrayed her again and again, eventually infecting her with a venereal disease.

Perhaps the only two things that Misuzu found solace in were her young daughter Fusae and her love of words. Misuzu’s mother insisted that she stay in school until she was 17 – quite extraordinary for girls at that time in Japan – and her education, and her many free hours in the bookstore provided her with the liberty to develop an extraordinary sensitivity and a powerful, free-flowing imagination. By the time she was 20, her talent as a writer of children’s verse was recognized by several different literary magazines, and she began to carve out a bit of fame as a poet. But Misuzu’s husband eventually forced her to stop writing.

After four years of marriage, she had had enough, and chose to leave her husband. However, Japanese law at the time gave Misuzu’s husband the right to custody of their daughter. The night before he was to come to take Fusae away, Misuzu wrote her husband a letter asking him to allow Fusae’s grandmother to take care of the young girl.

Then she took her own life. Misuzu was 26 years old.

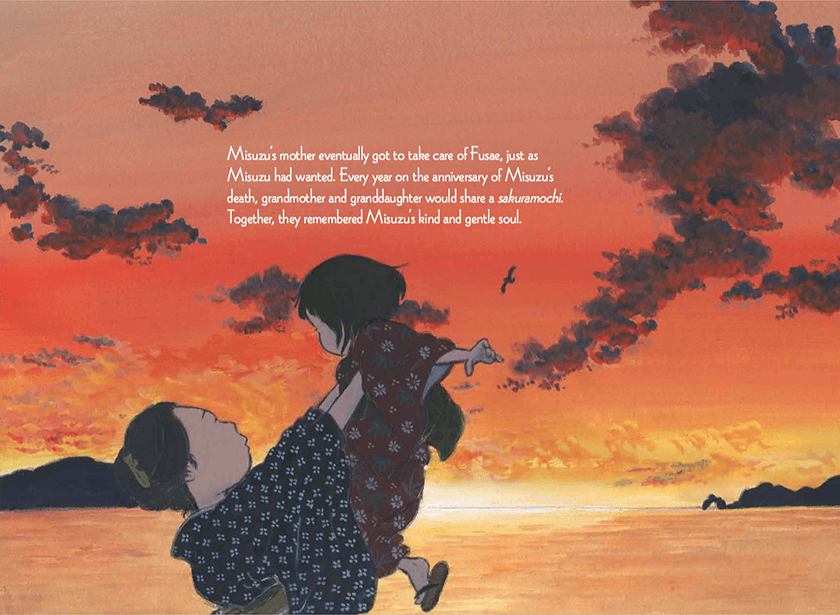

Aside from the fact that Misuzu’s husband did grant Fusae’s grandmother custody, and that Fusae grew up and turned 90 years old last year, there might seem very little good to reclaim from this story of a kind soul cut down too soon.

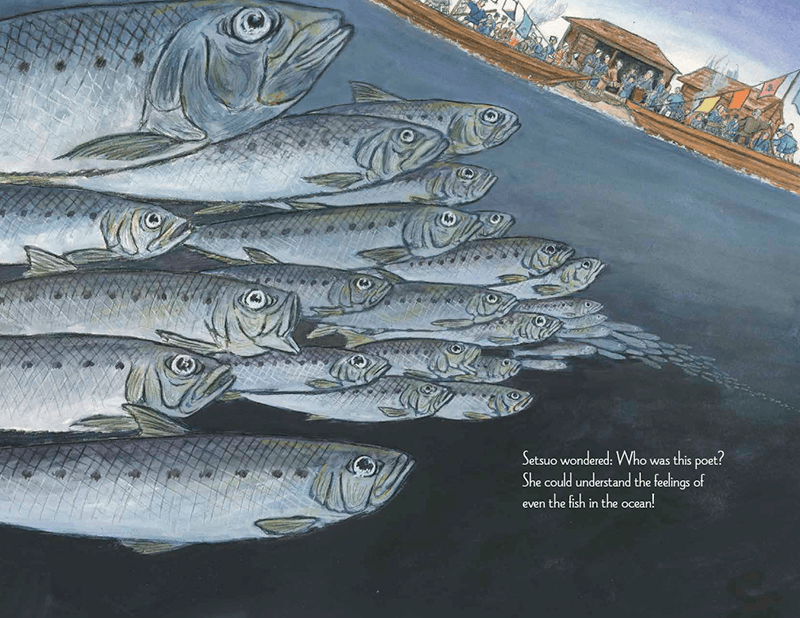

But a few of Misuzu’s poems made their way into anthologies and were taught to Japanese children in school. One young poet who was inspired by Misuzu’s verse was Setsuo Yazaki, who was touched by the thoughtfulness and the unique perspective of one poem in particular:

At sunrise, glorious sunrise

it’s a big catch!

A big catch of sardines!

On the beach, it’s like a festival

but in the sea, they will hold funerals

for the tens of thousands dead.

(“Big Catch”)

Setsuo would spend 16 years trying to find out more about Misuzu and her poetry. Finally, he tracked down her younger brother, who had held on to three of Misuzu’s writing notebooks, which contained all 512 poems that she had written during her lifetime. By the mid 80s, all of Misuzu’s poetry had been republished. Her former home was turned into a museum in 2003, and has been visited by 1.5 million guests since it was opened.

But in the wake of a much greater tragedy, Misuzu’s words would find an even larger audience, and provide comfort to even more.

After disaster struck on March 11, 2011, television stations in Japan stopped broadcasting ads, and replaced them with public service announcements. One of them was a dramatization of Misuzu’s poem, “Are You an Echo?”

If I say, “Let’s play?”

you say, “Let’s play!”

If I say, “Stupid!”

you say, “Stupid!”

If I say, “I don’t want to play anymore,”

you say, “I don’t want to play anymore.”

And then, after a while,

becoming lonely

I say, “Sorry.”

You say, “Sorry.”

Are you just an echo?

No, you are everyone.

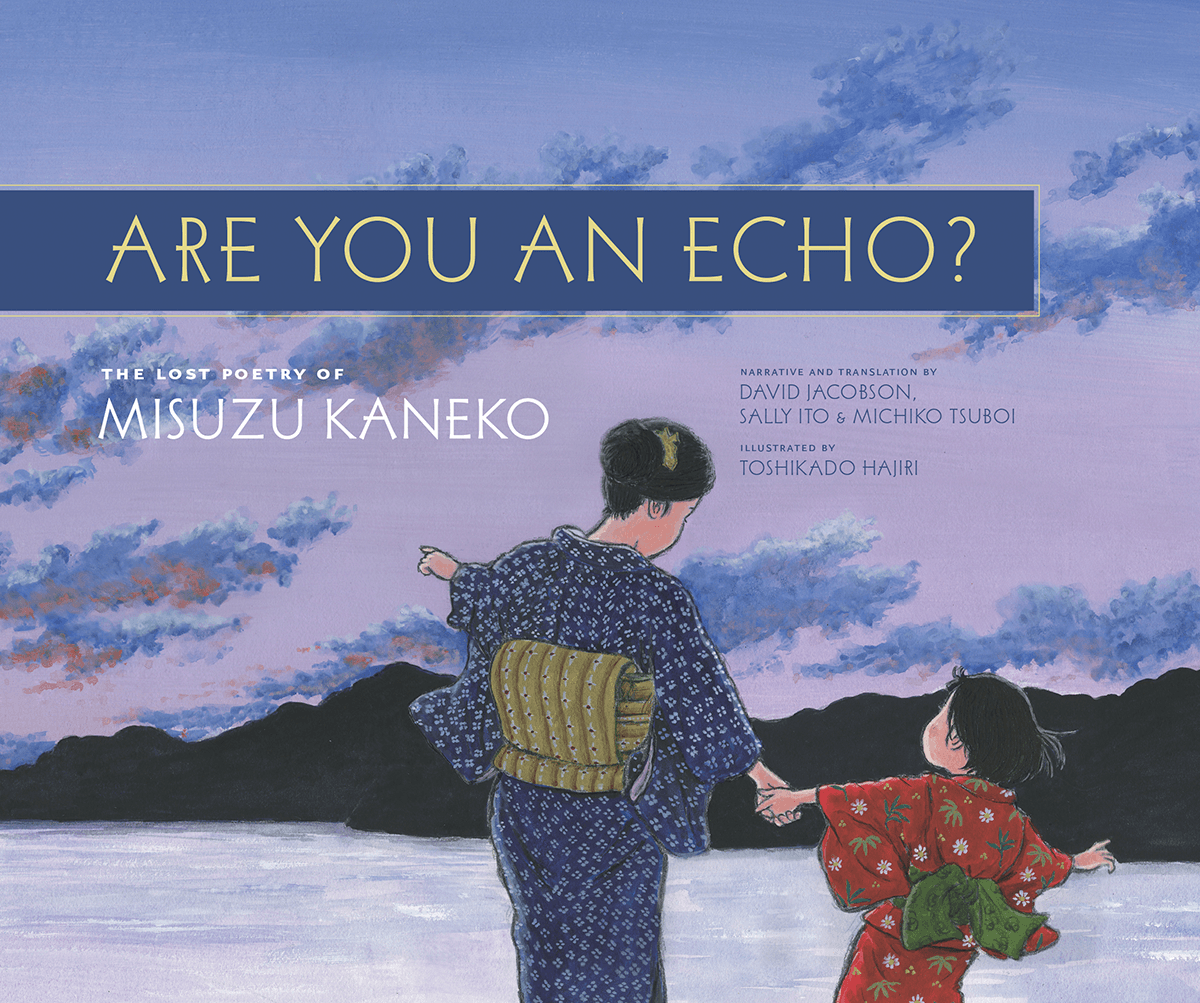

This is the story told in Are You an Echo?: The Lost Poetry of Misuzu Kaneko, a children’s book that was written and translated by David Jacobson, Sally Ito, and Michiko Tsuboi, and illustrated by Toshikado Hajiri. Intended for children from the ages of seven to 14, it presents the tragic story with a delicacy that befits the sensitivity of Misuzu herself, and with images that bring the poet’s story to life, but the poems as well.

On the 114th anniversary of Misuzu Kaneko’s birth, we spoke with David Jacobson about the editorial decisions involved relating a tragedy to young readers, the unique charms of Misuzu’s poetic vision, and the ability of a poet writing at the beginning of the 20th century to find resonance with readers all around today’s world.

Even though this is a book is geared mostly to a younger audience, can you tell us about the book team’s decisions about how to explain the negative details of Misuzu’s life, and how much of them would go into the book?

The members of our team had a particularly vigorous discussion regarding whether and how we should express the difficult parts of Misuzu’s life, especially her suicide. Partly because of our common journalistic background, Bruce Rutledge, publisher at Chin Music Press, and I felt strongly that we should relate the facts of Misuzu’s life, though gently. We felt that no matter how young, they deserved the truth, and would sense it if we were being evasive. We felt that was especially important since one of the hallmarks of Misuzu’s career was the emotional honesty she offered to her readers.

From a writerly perspective, what are the things that most appeal to you about Misuzu’s verse?

First, her poems transcend great differences in culture and time. Though she wrote them nearly 100 years long ago, and in the context of a culture so different from that today’s children, say, in North America, experience, they speak to an emotional truth that children (and former children) anywhere can relate to. Who as a child hasn’t had the experience of commenting on something, like the narrator of “Wonder,” and then having an adult tell him or her, “That’s just how it is”? But what makes her so attractive is the palpable sense of kindness and empathy that she exudes in her verse. She cares for the fish in the sea, the fish on her plate, the snow under feet, even how “last year” feels, once the new year rolls in. She cares about things most people don’t care about, or don’t even notice.

A lot of English-language poetry for kids today employs humor or nonsense words and is girded in rhyme. That may appeal to kids, but, I think, tends to mark such poems as only for kids. To Misuzu’s credit, she grapples with difficult issues and emotions honestly and in simple language that resonates with both kids and adults: like the guilt and sadness a child feels after taking a treat not meant for her.

More and more, people look at poetry as something rarefied – perhaps something that doesn’t really touch people’s daily lives: maybe it’s just something that is studied in a classroom. How do you think that Misuzu’s poetry defies this idea?

That may be true in the West, but less so in Japan, I think. You’d be astounded to see how often the name of this early 20th century poet keeps popping up in news stories and on Google. Every Japanese under a certain age has heard of her, and knows her most famous line, “minna chigatte, minna ii” (“we’re all different and that’s just fine.”) I think Misuzu’s poetry defies this idea because of her emotional honesty, ability to convey universal truths of childhood, and kindness. I think that explains why her poetry has been translated into 11 languages, several of which were published by amateurs who just loved her poetry and wanted to see it in Hindi or Farsi or French.

Do you have a favorite from among the poems that are included in Are You an Echo?

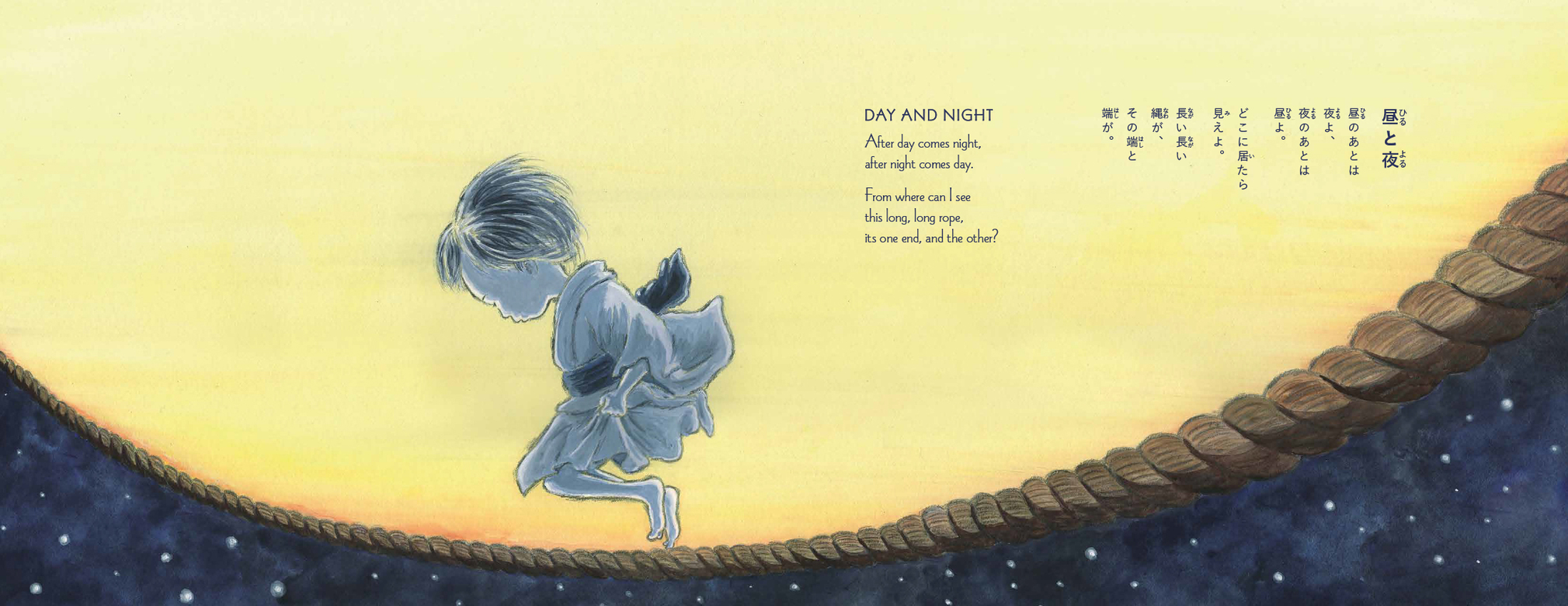

One of my favorites is the last poem in the anthology, “Day and Night.” Sally Ito, one of our co-translators suggested this, as she wanted to include one of the more philosophical and “challenging” poems though it might be a stretch for some of the youngest readers. In just a few words, Kaneko poses questions that probably occur to many children: Where does day stop and night begin? Does time have a beginning and end? Illustrator Toshi Hajiri complements the poem brilliantly by envisioning a child jumping rope, which divides night and day. We struggled a long time trying to translate this poem. It’s seems so simple, and something that a child would ask, and yet contains a very deep, philosophical question.

If there is a single message that readers might take away from “Are You an Echo?” what would it be?

I think Misuzu challenges us to look beyond our normal field of vision to see things from new and unexpected perspectives. In this age of increasing introspection and xenophobia, she reminds us how important empathy is in being human.

Are You an Echo? is available at larger bookstores in Tokyo, and online at the following locations:

http://bit.ly/AreYouanEcho (Amazon US)

http://bit.ly/AreYouanEchoJP (Amazon JP)

You can also order from JULA, the book’s Japanese distributor, here: www.jula.co.jp/web_cart/detail.php?n=189&p=0