Tokyo’s Wicked Yoshiwara Lives ( Just Barely ) On…

by Bob Cutts

PART I

They’re gone now, all of them.

The great somber evening bell of Iriya; all the laughter is stilled. The lanterns are taken down and the last cherry blossoms are as extinct as the gentle dreams of the girls who watched them fall.

They’ve even, for God’s sake, taken away the river.

If history repeats itself, it must be to the countless foibles of man that is owed its poor memory. While it recalls the Yoshiwara is still a red light district, perhaps we can pardon its forgetting that it was once and for 300 years Yedo’s splendored walled city of pleasure—a haven of dreamers and poets, thieves and lovers; a hell of the passionate living and the spiritually dying.

The city that sex built.

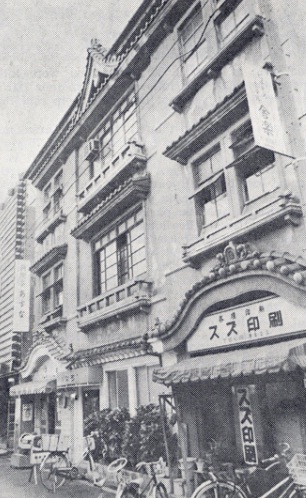

Yes, the Yoshiwara is still here. A dozen blocks of greying, oxidizing, two-story Taito-ku. The streets bear the same old names, none of them telling now of the little legends and mighty secrets, the raptures and tears they once held. All of them whispering of it.

Tacky now, in the neon glare of 60 Turkish baths. Still a red light district.

Yoshiwara. . .

The great carnivalesque houses laughing out onto the Naka-no-Cho, their alabaster women teasing and pouting for the windowshopping men who strolled and stared and desired. The exquisite clatter of a famous oiran, a Princess of the Whores, out on the street in a miniature parade with her retainers to take the air and to take the stares of dumbstruck peasants and lusty samurai. Dressed like a shimmering silver cloud.

Yoshiwara. . .it breathes in the ear like a lover’s sigh of ecstacy. Or maybe a harlot’s.

“This is the epilaph of Yoshiwara,” states the gray gravestone in the tiny shrine where the back wall once ran. Perhaps.

The great houses are burned down by America’s bombers and paved over by Japan’s progress, and the towering Kado-Ebi, where the celebrated sculptor of the Three Monkeys, Jingoro Hidari, once carved a wooden lobster that was so real it “moved” and bequeathed the house its legendary name, is now a hulking Sapporo Beer warehouse.

But the graceful curve of 50 Teahouse Road still leads from Looking-Back Willow to where the Great Gate stood…and orgasms arc still bought and sold in the neo-antiseptic chambers of the Turkos.

There’s still a memory tucked here and there, and a passionate gasp or two of life left in the Yoshiwara.

“The Moor of Good Luck” was its name when it opened in 1618. The moor was the rush field that the new Shogunate of Tokugawa had allotted to Shoji Jinyemon, Prince of the Courtesans, on which to gather together all the houses of ill fame in Yedo. The Good Luck was the unending stream of customers that immediately poured into them.

Moral appeals were not what had prompted the court—it was when Shoji pointed out the efficient espionage system such a “town” would offer for keeping track of the footloose plotters, rogue samurai and sundry troublemakers of that turbulent era that they saw the basic qualities of his idea.

The shogunate wrote five rules of order, or one might say disorder; all prostitution in Yedo was confined to Yoshiwara; no guest was to be harbored in the quarter for more than 24 hours, brothels should not be large or luxurious buildings; the girls should wear only plain clothes (no one should seem to enjoy any of this, you see), and records of all guests should be kept. For the government, of course.

With ebbs and flows—ebbs mostly in architecture and fashion restrictions and flows mostly in police eavesdropping—these are the basic laws that governed, or tried to govern, the Yoshiwara for three and a half centuries.

A dream of Spring-tide when the streets

Are full of the cherry blossoms. Tidings

Of the Autumn, when the streets are lined

On either side with lighted lanterns.

—Inscription on the

Great Gate of the Yoshiwara

“Yes, I can remember the cages. And the colors and lights—that was the best thing. In every season there was something: plum trees in February, cherries in April, the lanterns in the fall. The oiran would parade at Sakura, the best girls from the best houses in their best kimono. It was like a movie. It was better than the movies.

“But in Taisho 4 they stopped the parades. After that, the color evaporated.”

He shifts birdlike in his perch on the little stool, and the air conditioner hums to itself. He is 69 years old now, born in the Yoshiwara, son of a soba shop owner whose front door opened onto the glittering main avenue of the quarter, the Naka-no-Cho.

He still owns the soba shop, still in the same place. Though now the glass panes of the door are frosted and grimy and there is nothing to see through them but the beer warehouse. And his son tends to handle more and more of the business these days.

“There’s nothing left of it now. Nothing. The houses…some of them were eight stories high. Beautiful. The best ones, like the Kado-Ebi, would take customers only on reference from houses that were in the ‘go-between’ business.”

“The gorgeousness of her wearing apparel almost defies description. Her dress consists of a long robe of richly embroidered silk brocade. Her head is ornamented by a dazzling glory of hair pins (made of the finest tortoise shell) which glitter around her head like the lambent aureole of a saint, while her ravishing beauty is such that the mere sight of her face will steal away one’s very soul. .. .”

—On the Yobidashi, or 1st-Class, Oiran of the Yoshiwara, by the novelist Kyoden

“Most all the girls were from the country. Really, only 20 per cent could be called pretty— the rest were average. Makeup and kimono was where most of the beauty came from.

“Maybe 10 or 15 per cent of them were from the Tohoku, and had actually dreamed of coming to the Yoshiwara to become famous oiran. There was no chance of marriage at home, and they thought they could find fame and fortune here.”

“These Zegen (procurers) sent agents into the country to buy, beg, borrow or steal women and girls, whom they brought back and locked up securely till the moment of their absolute transfer into the hands of brothel-keepers. How they maltreated the poor wretches whom they had kidnaped may be inferred from the fact that the owners… were in the habit of stripping the girls absolutely naked every night, and hiding their clothes under their own futon lest the unhappy victims should escape.”

—The Nightless City by J.E. DeBecker

“The men who owned the houses—some inherited them, but most had to fight their way up from scratch. Like any other business, the men who got to the top were mainly hard-working and honest. Contrary to the movies made about Yoshiwara most of them were fine people: they were strict, but not cruel to the girls. It wasn’t like you read in the novels—cheating moneylenders out buying up the daughters of starving farmers.

“The girls used to come here to my father’s place to eat and talk. Most of them didn’t come to the Yoshiwara by choice, so naturally they weren’t happy at first. But they seemed to adapt quickly, and many stayed on when their five-year contracts were up… .

“…Things were booming right up until the war—even during the war. But the firebomb raids wiped us out. Everything burned. I lost my third daughter. All of us left after that, got out to the country.

“It was the Occupation when we got back, and the Occupation authorities had urged the reopening of the quarter for GIs. It was different, of course: the girls then all came here on their own, after the money. The place boomed again for a while—but then in 1958, they closed it down for good.”

“The commingling cherry blossoms, blending together into one dense mass of soft fleecy rolling cloud which braids the trees with visible poetry and transforms the avenue into a veritable fairy bower of pink and white flourescence, the dazzling glory of the electric lights and the flashing brilliance of thousands of crested lanterns . . . have earned for it the appropriate name of Nightless Castle.”

—The Nightless City

“The streets were pitch dark at night, that was the saddest thing. We all got together to raise money for lights, to try to bring back some of the grandeur. . .but it was never the same, even after the Turkos sprang up.

“The old houses were the life of the Yoshiwara. The Daimonji is a park now, and the Inamoto is just a company building. But it doesn’t matter, I suppose. Anyway, I’m an old man now—I tend to forget these things. . .”

(Continued in ‘Yoshiwara’)