by Hal Drake

SYDNEY—It was 10 days of glory for the lame and blind—even the blighted.

At the 2000 Paralympics here, they were not pitied, shunned or patronized—only extolled as extraordinary beings who fought beyond misfortune and infirmity to be laureled on the same ground vacated by able-bodied Olympians only days before.

Why, then, this onrush of 3,800 cripples from 123 countries?

Weren’t these wastebasket humans whose injured banned them from the playing field and often office and classroom?

The answer goes back to post-World War II England where a large hospital at Stoke Mandeville was full of maimed veterans. England owed them more than a token pension and a tin cup. Dr. Ludwig Guttmann, a far-seeing neurosurgeon, noted that wheelchair patients quickly became masters of rapid and proficient movement.

They often turned and steered the wheel with one hand and left the other free to grasp and hold. Couldn’t that hand, with determined practice, keep a basketball in full dribble? Why shouldn’t handicapped men be agile sportsmen?

And so it was by the time trumpets sounded for the 1948 Olympics, a revival of the every-four-years international athletic tournament deferred during eight years of war. A successful idea expanded to many places, such as Birmingham Veterans’ Hospital in California where wheelchair basketball was shown in “The Men,” in which Marlon Brando masterfully portrayed an infirm veteran.

Imaginative and compassionate officials pushed a good notion further, into other sports and other countries. In 1960, “Paralympics” first appeared in sports-page headlines, telling of games that had closely followed the Olympics in Rome—the same stadium, the same pool, the same track and ground.

Could Guttmann have had any idea what he had brought about?

Could he have foreseen what would happen in Sydney 2000?

David Hall is a poker-faced tennis technician, skillfully reeling from serve to lob, deftly defending the International Wheelchair Tennis title, besides being the first Aussie to win a Paralympics championship.

He’ll handily beat handicapped Yank Stephen Welch for the grail of gold but not without hard effort. Hall is used to that, going back to an upward struggle that began when he was hit by a car and left legless at 16. He disdains the definition “disabled,” traveling six months a year to play, win and show everybody it can be done.

One thing that gets you about these Paralympians is their sense of shrug-off gamehess about ignored or forgotten injuries. There is Anthony Clarke who has the thoughtful look of a bearded guru and won the 96-kilogram judo title in Atlanta. He won’t do as well this time, but will still impress and inspire.

Clarke has been handicapped for 22 years, the aftermath of an auto crash and flying glass that left him unable to see even a remote blur in a gray haze. Watch him now as he leaves a constant companion, a black Labrador guide dog, to brace his hand on a helpful shoulder and be led to a judo mat, where a referee will make sure each man has equal grasp on the other’s judogi.

Clarke will be beaten by an equally blind Briton, referring himself to a Paralympics article of faith—being here is what it’s all about. He isn’t bitter about the wrong-turn change in his life. “Not really,” he says. “The accident was my fault. I only had myself to blame and I had to live with that. The biggest problem was dealing with society, the negative attitude people have against you. They expect you not to do things than to do things.

“Gee, how can you do that?”

As athlete and motivational speaker before corporate groups and classrooms, Clarke shows and tells.

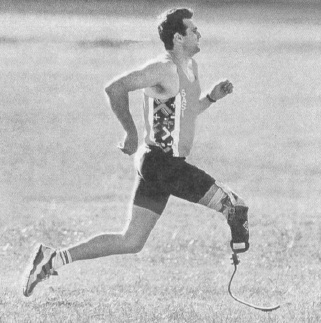

Could anybody have had a tougher break than Neil Fuller? Injured in football, Fuller developed complications that compelled surgeons to clip him at the right shin. Did this make him a bitter, sidelined has-been, a mind-and-body loser who would never compete again? Wearing a false foot that looks like an elongated shoehorn, Fuller sprinted home to four Paralympics gold medals.

It was a blue and bitter Christmas, 1985, for swimmer Brendan Burkett who lost much of his left leg to a hit-and-run driver. He doesn’t feel cheated because he was disabled and the other dude got away dirty. “You’ve got to go on and live,” he asserts.

Now imagine again disabled men on wheels, riding out on haunch or stump for an aberration called “wheelchair rugby.” One of the toughest games on turf played on a hard gym floor. How could such a game be anything but a bow-and-curtsey demonstration, a kind of minuet, with for-real contact and risk of injury forbidden? How? Just watch.

Is this a time slip, with spectators on the stone steps of the Roman Colosseum, or are movie stuntmen re-staging the chariot-race crashes in “Ben Hur“?

The hand chariots here can be wedge, battering ram or phalanx—prying past the prows of rivals or smashing through then tightening as a shield. Rules and fouls? They have to be written down somewhere, but not as American Steve Pate flings Aussie George Hucks over and down and reaches out an apologetic hand to help him up. A varnished floor is harder than a soft field of soil and grass. But Hucks will upset Pate’s chariot and the game will crash on to a wheel-to-wheel finale. The Yanks are hairline winners at 32-31. Should the jubilant victors be sporting the helmets of Roman Legionnaires?

Such brusque and rowdy behavior would be lost on Siobahn Paton, the gracious 17-year-old and athletic prodigy who would win five swimming titles in five days and add another on the last day of the games.

Waves of cheers washed over Siobahn. In another time, there would have been jeers. She is intellectually disabled, with an IQ below the normal level of 100. As a schoolgirl, she was the butt of taunts by ill-bred bullies who railed at her as a “retard.” A dogged coach and patient elders showed her the path to accomplishment and self-esteem.

She was not the Golden Girl, blonde and fair, bubbling over with pride and modesty.

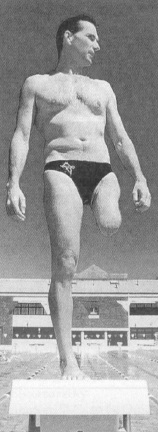

But is she to be any less applauded than Stephanie Dixon, the Canadian relay swimmer who stood with precarious poise on a diving board and deftly took a baton to launch herself with skilful kick and stroke—on one leg?

Lisa Llorens, winning gold in high jump and long jump, nicknamed herself “Cheetah”—the veldt cat naturally engineered for speed and grace. But Llorens, too, might have been wadded up as a throwaway that would have to be hand-led through life.

She is autistic, slow to discern and learn, with delicate emotions that can snap under stress, much like the Dustin Hoffman character, Raymond, in “Rain Man.” But her leaps of faith at the Paralympics paid off.

Paul Bird, chief of mission for the Aussie Paralympic team, puts heart and dedication in his work. He just missed a berth on the swimming team that went to Munich and would never be an able-bodied athlete again, losing his right leg in a motorcycle crash. He has since seen the skylines of Barcelona, Atlanta and many places, always in the wings of the Paralympics.

There are no losers or throwaways at the Paralympics—only athletes who earn emotional gold just by being there.