How can I reach my ageing mother

Who waits for me at home

Not knowing that I am about to die?

A last poem by 2nd Lt. Shigeru Nakata, 21 d. off Okinawa, May 28,1945

There is something utterly repulsive to me in the idea of gifted young men diving their planes to destruction in warfare—did the kamikaze pilots of the Pacific War have to do that?

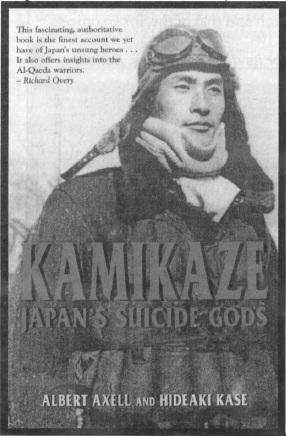

The question is raised by the publication of a book titled Kamikaze—Japan’s Suicide Gods written by Albert Axell, an American writer based in London, and Hideaki (“Tony”) Kase, a celebrated conservative intellectual, living in Tokyo. This is a first considered effort on the topic written in a quarter of a century—since a Columbia U. scholar, my friend Ivan Morris, included a chapter on kamikaze pilots in his monumental last work The Nobility of Failure: Tragic Heroes in the History of Japan, published in 1975.

Just to hold their tome in my hands—Tony was kind enough to give me a signed copy—is something that goes against the grain. I do not want to think about 6,000 young, mostly very young, men dashing their aircraft against U.S. ships at sea in 1944-45. Nor do I want to visualize the fate of the sailors on those ships.

Usually, the kamikaze flyers have been represented as pious, patriotic souls who were inspired to lay down their lives for their country. Yet my own feeling, confirmed by reading this work, is that often enough they were shepherded, coaxed or just plain ordered into their attacks rather than just volunteering.

The first kamikaze pilot in history—he was ace flyer Lt. Yukio Seki—thought that it was entirely wrong of his superiors to send him out on a suicide mission. It would be better, he thought, to let him sneak up on a U.S. carrier, drop a 500-kg. bomb on its flight deck and then wing it back to base, to live and fight another day.

Seki-san is recorded by Kase and Axell as saying that he only agreed to do what he did—he went out on a last mission off the Philippines in the fall of 1944, when the kamikaze strategy began—because he received a direct order. He was to play the role of guinea pig and role model, it turned out.

“Japan’s future is bleak if it is forced to kill one of its best pilots,” he said. “I am not going on this mission for the Emperor or for the Empire… I am going because I was ordered to” (Page 16).

A quote as good as that sounds almost too good to be true. But I trust Axell, the main researcher, and Kase, the main writer, to have got their facts right. The remark, according to them, was made to a reporter on the spot in the Philippines. It seems that Lt. Seki expressed his dissent “privately,” i.e. off the record.

This book does a good job, in fact, of laying out the official story—the cover story, I am tempted to call it—and the truth. At the start of Chapter 2, we learn that: “Admiral Takijiro Onishi, the aviation pioneer, inaugurated kamikaze tactics when he arrived in the Philippines in mid-October 1944 and proposed the setting up of Special Attack units. Not a single officer opposed him.

“Author Ivan Morris notes succinctly that the decision to adopt kamikaze tactics was approved in a matter of minutes but that the psychological (cultural?) foundations had been built up over many centuries.”

A later chapter massively qualifies this picture of total compliance with a bull-headed commander bent on sending the nation’s best pilots to an early grave—to be followed by younger pilots who had hardly learned to fly before they were thrust into action.

“From the beginning there were flyers who did not agree with suicide tactics,” according to the authors. “For example, Lt. Commander Tadashi Minobe, flight leader of a group of night fighters in the Philippines, was openly skeptical of Special Attack operations… A memorable Onishi-Minobe confrontation took place… in mid-November 1944 when Minobe was summoned to Clark Airbase near Manila to report to Onishi.”

Minobe is supposed to have told the founding father of the kamikaze strategy to his face that, in effect, he was out of his cotton-pickin’ mind. He did so at that encounter at Clark. Kase and Axell quote Minobe as telling Admiral Onishi as follows:

“First of all, suicide operations are outside military tactics. No commander should choose to employ them. I have my own tactics and I am not going to obey you in using my unit for that purpose, sir!” (Page 148)

Admiral Onishi prevailed by the age-old strategy of pulling rank. He let Minobe, too hot a customer to hold, go his way. But he forced his thinking on a working majority of officers under his command. It has been the same in many a war— let’s not fall overboard in rating the kamikaze pilots as somehow unique in history.

Just for example, if you were an infantryman serving on the Western Front in World War I— say on the Somme in 1916—and you were told to stand up out of your trench and walk into machine gun fire, you did what you were told, quaking in your boots, and like as not lost your life on the spot.

Hundreds of thousands of Allied soldiers did just that in the course of the one campaign in 1916. If they didn’t get shot, they drowned in the shell-holes—giant sticky puddles in the mud—or got hung out to dry on the barbed wire.

There was, to be sure, an element of volunteering, and of keeping up with your mates and not letting them down—not shirking your bounden duty.

Isn’t that how it was with the kamikaze flyers? The merit of this work, I would say, is that it makes all of the above relatively clear, while respecting the heroic dead.

Here is a vignette (Page 15) that makes it quite certain that there were two schools of thought within the Japanese military as regards kamikaze tactics in the fall of 1944.

The scene was an officers’ lounge at a base in the Philippines: “Lt. Commander Okajima, the head of the 203rd Air Wing, adamantly opposed suicide tactics… and engaged Flight Leader Tadashi Nakajima of the 201st Air Wing in a heated discussion. Okajima said: ‘Such tactics are impermissible! We should take our men back to the mainland and rebuild our strength and fight the enemy head-on. I will not allow a single plane to take part in tokko (suicide tactics)’.”

Okajima took his men back to Japan “the next morning,” according to the authors. Funny, it may have taken as much courage to say “No” to madness as to acquiesce in it.