Story & photos by James Mulligan

New Yorker Tom Byer has always loved soccer. He was a journeyman professional who pulled on his boots for whoever paid him to carry on living the dream. But just after he arrived in Japan, injuries dumped him on the soccer scrapheap. So how did he end up as head of the largest soccer education service in Japan and Asia, a national television celebrity and an Adidas Golden Boot winner? Weekender went on the road with Byer to find out.

The line of kids snakes away from the touchline of the soccer pitch, along the halfway line and all the way past the center-spot. There are maybe 400, all waiting patiently for their turn, holding their pictures, T-shirts, shin-guards or soccer balls they want signed.

The kids’ parents — numbers roughly equaling that of the kids — wait in the stands, digi-cams popping and flashing when it’s their child’s turn for an autograph.

Standing at a table on the touchline is Tom Byer, black marker-pen primed to sign everything that comes his way, joshing with the kids, sending them all home with hair-ruffling encouragement, the kids beaming because of their chance to meet “Tom-san.”

That’s how he’s known by the kids here, as well as by the thousands of soccer-crazy boys and girls all over Japan. Byer is the most important person in grassroots soccer in Japan. “Soccer clinics,” such as this one held in the port town of Shimonoseki, are what he does best.

The week before the Shimonoseki trip, Byer is sitting in his company Coerver Coaching Japan’s stylish offices in Omote-sando. He talks with an infectious passion and devotion about soccer, and about his transition from player to successful coach.

“I played soccer at my university in Tampa, spent some time in the professional soccer league in the U.S. and a year in England, playing in the semi-professional Ipswich-Suffolk League. I came to Japan in 1988, to play for Hitachi in the industrial league, the precursor to the J.League. I was a mediocre player though,” he says.

Byer was the first American to become involved in soccer in Japan. Unfortunately, he lasted hardly a season. Cumulative injuries brought a premature end to his career at age 28.

Sensing interest in soccer in Japan was beginning to pick up, he chose to stay. He saw an opportunity to run soccer coaching clinics for kids.

“They were popular in the States, so I thought they would be here.”

He started looking for a sponsor with which to run the clinics, cold-calling companies using the little Japanese he knew. He was also doing a little part-time coaching to pay the bills.

“One of the kids I coached told me his dad worked for Nestle. I called him, and found I was talking to the president of the company. I gave him a proposal for his company to sponsor a series of clinics in Japan, and he agreed.”

In the first year, 1989, Byer did 50 clinics.

The Nestle clinics became a big success. Each weekend, Byer and four other coaches would cram into a minivan and drive to different cities in Japan, coaching anywhere from 100 to 1,000 kids. Slowly, Byer began to make his name in kids’ soccer coaching in Japan, making vital contacts and becoming fluent in Japanese.

The early ’90s saw interest in soccer among youngsters at an all-time high. Around the same time, Byer heard about Coerver Coaching, a teaching method and philosophy aimed at young players, which was started by visionary Dutch coach Wiel Coerver, in the 1970s.

Byer sums up the philosophy: “Coerver Coaching teaches players to be attacking, attractive-type players. A study by FIFA (the Fédération Internationale de Football Association) says there are 200 ‘one-on-one’ situations per match. If you can teach one-on-one skills, then in a match, the more one-on-one’s you can win, the better chance your team has of winning. It is the keystone of Coerver Coaching.”

This philosophy equates with what is happening in top-level soccer today. The idea that only forwards need to be technically gifted is outdated. Teams such as Arsenal, Real Madrid and Valencia are proponents of having 11 technically gifted players on the pitch, all comfortable one-on-one.

Back in 1993, Coerver Coaching was well-known in Europe and America as the leader in youth soccer development, but unheard of in Japan.

So Byer convinced some business friends and Coerver Coaching International Director and world-renowned coach Alfred Galustian that it would be beneficial as a business and as an educational pursuit for kids to launch Coerver Coaching Japan.

The company (Byer and three employees) formed in 1993, the same year the J.League began. Riding on the coattails of the early successes of the J.League helped Byer: Clubs signed famous players such as Brazilian Zico, Yugoslavian Dragan Stojkovic and Englishman Gary Lineker, to play in stadiums packed to the rafters with converts to the beautiful game. Japanese kids had a new type of hero to try to emulate: the professional soccer player.

Coerver Coaching provided an outlet for those youngsters to practice their skills through the production of training videos and books.

“We started with a licensing deal, but we could see the potential, so we basically bought the whole thing.”

They now have the intellectual property rights and own the teaching method and business for the Asia-Pacific area.

The initial popularity of the J.League inevitably died down — attendances dropped by 25 percent between ’95 and ’96 — and so interest in the game cooled a little. It was still strong at grassroots level, but Byer had to work out how Coerver Coaching Japan could best tap this potential and best survive as a business:

“We came up with the idea of starting football schools. We started our first couple of schools and had tremendous success. Now we have 32 schools, from Sapporo to Kobe, and we are opening nine new schools in the first part of this year. We have close to 9,000 kids in our program.”

Already Coerver has graduated more than 200 kids who have ended up playing in the J.League. The current under-18 national team captain, Tatsuya Masushima, is a Coerver alumni. Coerver Coaching Japan now employs 70 people at its Omote-sando office and in its schools around Japan. It also has a full-time, one-year Coerver coaching school academy in Urawa for aspiring coaches. Not bad going for a business a shade more than 10 years old.

But Byer’s work as director of Coerver Coaching Japan is half the story. His popularity among soccer-mad kids in Japan means he has had his own manga strip in Koro Koro magazine for the last six years. It sells 1.2 million copies per month.

Byer works with the big-hitting companies in Japan: Fuji-TV, JAS, Coca-Cola. He has been the image character for Nintendo Gameboy soccer software, and has a personal contract with Adidas Japan. (Globally, Coerver Coaching has a contract with Adidas.)

He is also head coach of the Canon under-12 National Select team. “We play in international tournaments in Australia, America, everywhere,” he says.

He’s helped in training these kids through his work with the Japan Football Association at its eight regional training centers that identify the top 80 under-12 players in the country.

His celebrity status — the “Tom-san” phenomenon — came about through the Shogakukan-produced television show Ohasuta, on Channel 12.

“A friend, who was a cast member on the show, asked me whether I was interested in doing a football corner.”

He has appeared on the show since just before the 1998 World Cup. Thousands of kids tune in to watch Tom-san’s soccer corner every weekday from 6:45 to 7:30 a.m.

One of the most important and influential things Byer does is the “Tom-san elementary school visits.” Sponsored by Adidas and sanctioned by the JFA, the visits started in the build-up to the 2002 World Cup in Japan, focusing on the ten World Cup cities. Now, Byer visits 12 schools a year, taking over the gymnasium for a morning or afternoon of soccer skills training. Amazingly, this all happens during normal lesson time, something almost unheard of in Japan.

The school visits, and everything else Byer does, are aimed towards further strengthening the link between his work and the growing soccer population in Japan. His TV show and manga strip both promote the school visits, which promote Adidas, which promote Coerver, which promotes Adidas, which promotes the school visits, which promote the TV shows and manga strip. His — and all the related companies’ — events and products are constantly feeding each other, helping each grow.

Through Adidas he also does a lot of events with Japanese national team players such as Shunsuke Nakamura (the JFA also has a contract with Adidas), and when Real Madrid came to town last August, Byer did a special event with the “galacticos” — David Beckham, Zinedine Zidane and Raul.

“Just to take care of Real Madrid, to stand on the pitch and work with these guys. It was great,” Byer says.

Byer has worked hard to get to this point though:

“Over the last 15 years, I’ve developed a network of contacts over the 48 prefectures.”

That’s why Adidas uses him. When Oliver Kahn (Germany and Bayern Munich goalkeeper) came to Tokyo, they asked Byer to invite 50 children along. He delivered 500.

“I just pick up the phone and call a couple of guys,” he says casually.

Some of the big advertising agencies don’t have networks such as this.

“It’s business-like when the agencies do it anyway — people are wary. But I do it, and I’m just talking to friends.”

And Byer still hits the road every weekend, doing soccer events and maintaining this special network.

“I love spending time with this family of friends around the country, and going to all these different places.”

And that’s why he’s standing at the table on the touch-line of a soccer pitch on the outskirts of Shimonoseki. He’s been invited to do a special weekend event.

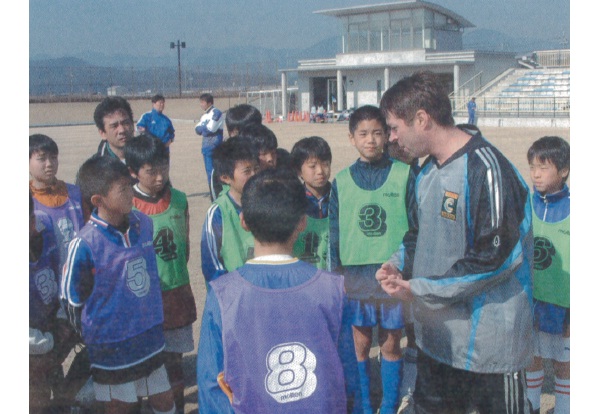

Saturday sees Byer holding a training session for 80 of the most promising under-12 players in the area, before conducting a lesson for the local coaches in the evening.

Sunday is the big event. The Shimonoseki mayor and an NHK camera crew turn up to watch Tom and his assistant Kenji Hiraki work with the 400 kids, modeling different tricks and turns for them to try to copy. It’s a soccer fun day for the kids — and the watching parents.

Afterwards, Byer works frantically to give his autograph to all the youngsters before it starts raining. We’re lucky. As Tom, Kenji and this writer are whisked away from the stadium to the hotel with goodbyes ringing in our ears, the heavens open. Not that a little bit of rain is going to wipe the smiles off the faces of the kids.

On the flight back to Tokyo I ask Byer — a youthful 43 — whether he misses playing competitive soccer. “I play every weekend with the kids. Some people say mockingly, ‘Ah, you play soccer with kids.’ I say, ‘Hey, you come out and play with some of the kids in our school.’ We’ve got some amazingly talented kids.”

Two weeks later, in between which Byer has been to Sapporo, Matsuyama and Yokkaichi, we travel down to Yumegaoka, Kanagawa, to one of the actual Coerver Coaching schools. Byer dons his soccer shoes and gets down to what is his bread and butter — and what he’s happiest doing: teaching kids to become better soccer players.

The session ends with a game offutsal (five-a-side) with Byer, this writer, the coaches and kids. Byer is right. These kids really are good.

Taking a break towards the end, Byer talks enthusiastically about the future, giving off the vibe of someone with the world at his feet. Or at least Asia:

“We’re focusing on expanding Coerver outside Japan. We’re developing schools in China and Korea.

“In Japan we’ve got more demand than we can supply. We’re trying to open as many schools as we can.

“There is a direct link between where we open up schools with community soccer becoming stronger at the under-12 club level. In Azamino we had a big school open up. Since then the local under-12 club makes regular visits to the national tournament. The word is out: a Coerver Coaching school in your neighborhood is not a bad thing to have.”

A great boast for Byer considering how popular soccer is becoming in China and other Asian countries.

Byer is also getting more involved in television. He’s starting a new 30-minute official J.League program, focusing on soccer stories cropping up through the week.

But even a Japanese television celebrity can get star-struck. A highlight of Byer’s career was in 1997, when he was awarded the Golden Boot (the Oscars of the soccer world) from Adidas International for being the leading coach worldwide for youth development — the same year the Golden Boot for top scorer in the European leagues went to Ronaldo.

Topping even that was when he was asked to be the host at the unveiling of the 2002 World Cup Golden Ball.

“I got up on stage with Franz Beckenbauer, Aime Jacquet and Carlos Alberto Parreira, the three past winning managers of the World Cup, in front of the entire world media. Now that was mind-boggling.”

But well deserved. Byer has traveled hundreds of thousands of miles around Japan and helped improve the soccer skills of thousands of kids.

He is quick, however, to acknowledge the help of others: “I started doing all my work before soccer was popular, and the popularity of the game has risen alongside my career path, but I couldn’t have done it without my friends.”

A misplaced pass comes our way. Tom-san can’t resist the stray ball. He peels away and rejoins the game of futsal. Rejoining some of those friends that helped make it all happen.

* * *

Thanks to Kenji Sugihara and friends in the beautiful port town of Shimonoseki for their hospitality.