The Weekender caught up with the American-born, Kyoto-based artist who has a retrospective show this month in Tokyo.

This year in Japan, the changing of the seasons hasn’t been a straightforward affair. With record highs in Tokyo this month, it’s hard to be sure exactly when we’ll be able to declare that autumn is here. But when it finally settles in, we’ll know it: there will be new colors on the leaves, frost on our breath, and sometimes, more reflective thoughts on our minds. With the beauty of our changing environment and weather that can get us thinking, some of us also turn to something that can outlast the changing seasons: art.

The Artist

We caught up with Daniel Kelly, who has a retrospective this month, to talk with us about his work, and we started on the subject of art as a way of looking into the past. As he explained, whether it’s cave paintings or American abstract art from the 80s, art opens a window into another era, and the way people lived, thought, and saw during that time. Going further, he says, “I don’t think we care to look back so much as being contemporary is the one thing we cannot avoid. We leave a little record of our time.”

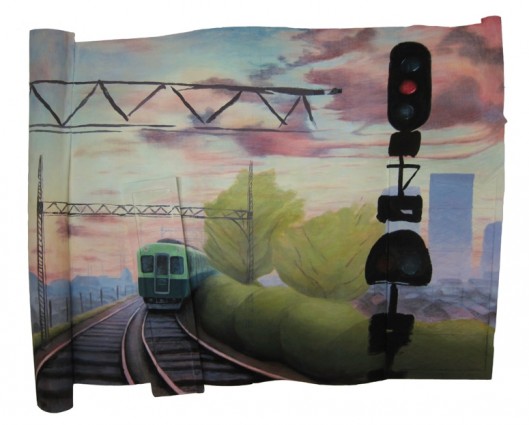

The year 1978 found Kelly in San Francisco, where he was making sculpture at Fort Mason Center. On what he thought was short visit to Kyoto, Kelly visited the studio of Tomikichiro Tokuriki, a twelfth generation woodblock printer. He had seen Tokuriki’s work in a book of prints that he’d picked up as a student, and one of his teachers, Mort Levin, recommended that he check him out. What he wasn’t expecting on his visit was for Tokuriki to ask him to be his student. Most of the printmaker’s students lived full-time at the studio, but Kelly supported himself at first by teaching English in Osaka and commuting to Kyoto when he could. He even made himself a small watercolor set from a makeup kit so he could paint on his commutes between Osaka and Kyoto.

“I live with an image. We battle and we communicate.”

Studying with Tokuriki gave Kelly a chance to broaden his technique, but it also taught him many lessons about being a professional artist; Tokuriki was also his first buyer. He introduced Kelly to the Hankyu Department Store in Osaka, where he had his first show: a collection of landscapes filled with “mist, rain, bad weather, and landscapes with horizons you couldn’t see.” Even though Kelly admits he’s not big on landscapes, and much more on “expressing a mood,” his landscapes sold out. He’s been showing ever since, here in Japan and around the world.

The Art

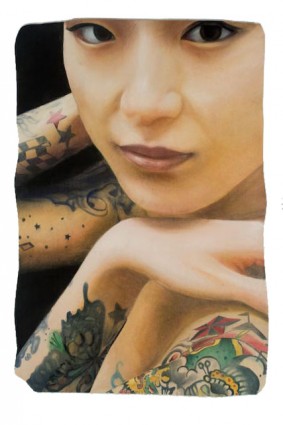

Kelly’s interests run from art, to politics, to psychology (he has a Master’s degree in the subject) and music. As he explains, “my ideas

come from everywhere: things I read, images I see. But I like working with mental images. I start with an idea and then search for images to build the idea, like photos or making sketches. Most of my works in the studio are not of things that exist.” Of course, bringing those images to life is never easy: “I live with an image. We battle and we communicate. I hate to lose. In the middle it is always the worst.”

His two preferred media are prints and paintings. One reason his prints stand out is the type of paper he uses—often heavier Thai or Nepalese paper, which has a rougher appearance and yields prints that differ, even in the same edition. As for the unpretentious nature—and cost—of prints, Kelly’s teacher Tokuriki told him something that he has never forgotten: during the Edo period, a woodblock print fetched the same price as a bowl of soba. This reminder of printing’s humble background has kept him from taking an elitist attitude towards his work, particularly when it comes to printmaking.

In keeping with his early background in sculpture, Kelly’s paintings are not limited to flat canvases. He paints on panels that are bent into undulating forms, and he often makes collages of heavy paper, bamboo and tatami mats, and other found objects on top of these panels. It is over this chaotic substrate that he paints, creating works that must be seen in person. One example is the massive piece, Futsu (Local Train), which is based on one of those tiny watercolor sketches that Kelly used to make on his Osaka-Kyoto commutes, over 30 years before.

We started our conversation with the subject of the past, so our last question was about the future of the art world. What trends did he think were on the way? “The art world is restoring a belief in beauty. For a while, people have been saying that beauty is trite, but I don’t think that’s so. Most of the people who say that really don’t make art, but they have been the ones dictating the rules. I’m happy to say that I think that beauty is about to be respected again.”

As the days continue to grow colder, that’s something that should keep us warm.

You can find out more about Daniel Kelly’s show at the Tolman Collection’s site: http://www.tolmantokyo.com

You can see a video of Kelly creating one of his large-scale pieces below: