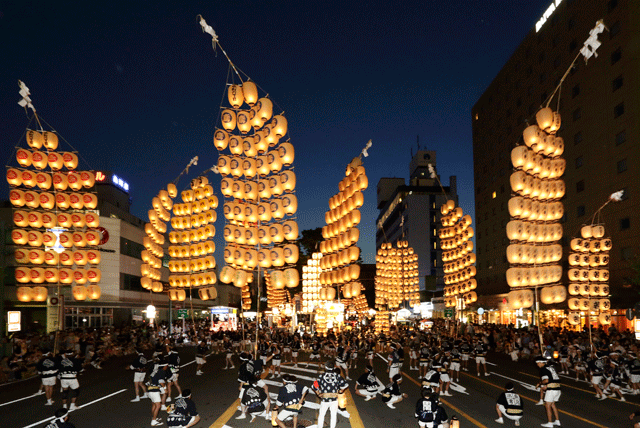

In the middle of summer, participants in Akita’s Kanto Festival set the night aglow with lantern towers that reach for the skies.

By Robert Morel

Legs tensed and set apart, the performer looks up, gauging the wind, feeling the sway of the long bamboo pole balanced in his open palm. The pole moves with the breeze, its 46 lanterns dangling like heavy-headed stalks of rice, golden before the harvest. Slowly the performer raises his hand, elevating the 12-meter-tall stalk of glowing lights higher into the air. As he smoothly shifts the base of the pole to his shoulder, lower back, and forehead, it is hard to tell whether or not the 50-kg pole has become an extension of the performer, or part of him. For a few minutes of pure concentration, there is just this one man and the tall lattice of bamboo and light—the Kanto. And then, as if able to sense the performer is at his limit, a teammate comes up for a turn. The Kanto is passed and the dance begins again.

Every summer in the city of Akita, 10,000 candle-lit lanterns rise into the air, shimmering globes of light swaying in the night sky. Every year the air echoes with the rhythm of drums, chanting, and cheering. Crowds flock to see the array of lights and the feats of strength and skill that make the Kanto Festival. One of Tohoku’s most famous events, the Kanto Festival is a combination of showmanship, competition, and pure spectacle. Symbolizing stalks of rice, the Kanto are paraded to pray for a good harvest, but also to bring good luck and ward off disease and misfortune.

The Kanto (the two kanji in the Japanese word mean “pole” and “lantern”) are made of a long vertical bamboo pole with lanterns hanging from thin horizontal crosspieces. At the top is the gohei. These paper strips act both as an offering to the gods and, more practically, a way for the performers to gauge the wind. Each Kanto’s lanterns are painted with a symbol of the community it comes from: some are simple ink calligraphy, while others depict colorful scenes, a number of which date back to feudal times. There are four categories of Kanto varying in size from the 5-kilogram, 5-meter-tall Yowaka to the towering 46-lantern Owaka, which stretches 12 meters into the air and weighs 50 kilograms. Yet using only one hand, the performer’s balance and move the Kanto with precision and grace.

It is unclear exactly when or how this 300-year-old festival took its current form, but it likely evolved from Akita’s traditional Neburi Nagashi Festival. Originally, children paraded through town with bamboo poles hung with wooden tablets inked with wishes, but as candles became more common the wishes were written on paper lanterns. Another theory is that it was influenced by Akita’s tradition of hanging tall lanterns outside of homes during the Obon holiday. However it originated, by the late 18th century there were illustrations of Kanto that looked like those used today. By the early 1900s, Kanto was popular enough that groups from Akita traveled to perform in Tokyo and other parts of Japan. Around this time, the name “Kanto,” the uniforms, and the performance style became more unified. More recently, the Kanto Festival’s popularity has increased dramatically, drawing in over a million visitors to the city each year.

Tests of Skill and Towers of Lights

Harvest festivals in Japan often contain a strong element of competition, with different groups trying to outdo each other, and the Kanto Festival is no exception. In the daytime, teams of Kanto performers compete in a show of skill, balance, and strength. Watching the performers merely balance the massive Owaka is impressive, but that is only the beginning. Moving with a fluidity and grace honed from many years of practice, and using only their balance and the Kanto’s weight, participants in the festival finesse the flexible bamboo pole into different curves. At its greatest flexion, the Kanto curls almost in half, nearly horizontal over the ground lanterns hanging down. Seeing the Kanto like this, bent like stalks of rice, heavy with grain, the connection to the harvest is clear.

While the daytime is a show of technique and mastery, at night the performance takes on a mysterious feeling. After sunset the Kanto are carried out once more. One by one the lanterns are lit. And then, to the sound of drums and flutes, more than 200 Kanto are slowly lifted into the air. These clusters of lanterns stretch down the length of Kanto Dori. Spectators line the streets, shouting praise and encouragement. The main event of the festival has begun. For the next hour and a half, the air is filled with music, shouts and cries of “Dokkoisho! Dokkoisho!” (Heave, heave!) as the performers maneuver and pass off the Kanto to one another. Looking up it is as if the Kanto are mysterious illuminated reeds blowing and shifting in the wind.

Seeing the Festival

The festival, held from August 3 to 6, is located an easy walk from Akita Station. Just follow the flow of people. In addition to the competition and nighttime parade, take time to wander around the festival area and witness some of the music and dance performances, and of course, sample some local Akita cuisine.

The easiest way to get to Akita is to hop on the Akita Komachi Shinkansen. The scenic ride through rural valleys and tall stalks of rice swaying in the breeze is a perfect way to put Tokyo behind you and get in the mood for the festival.

Beyond the Festival

The Kanto Festival may be the highlight of a getaway to Akita, but there is enough to see in the city that it is worth spending an extra day to see the sights.

Senshu Park, on the grounds of the former Akita Castle, makes for a pleasant escape from the crowds around the station and Kanto Odori. In addition to all the greenery, the park has a small museum done up as a faux castle housing antiques and armor.

Designed by renowned architect Ando Tadao, the new Akita Museum of Art is one of the most impressive indoor spaces in the city. In addition to its permanent exhibit—the centerpiece of which is a massive painting depicting Akita life thought the seasons—it hosts a variety of rotating exhibitions. Art aside, having a drink in the café that overlooks Akita’s Senshu Park and the old castle moat is a great way to escape the August heat.

To learn more about Akita’s Kanto, and try balancing one yourself, stop in the Neburi Nagashi Hall, a museum dedicated to the festival.

Akita’s baba-hera ice may sound odd—the word “baba” means grandma and “hera” means scoop—but this dish, made in the shape of a rose fashioned from strawberry and banana ice cream, has become a local favorite. Why it is always an old lady is unclear—but the colorful beach umbrellas usually draw the queues for this sweet Akita tradition.

Sponsored Post