The last time Kohei Uchimura lost an all-around gymnastics competition, George W. Bush was the American president and the global economic crisis triggered by the Lehman Shock was still months away. A sporting phenomenon who’s widely considered the greatest gymnast of all time, Uchimura does more than just beat his opponents: he tends to wipe the floor with them.

So what is it that makes the man known as “King Kohei” tick? And what was he like as a child? Wanting to find out, Weekender recently spoke to the 27 year old along with the woman who knows him best: his mother Shuko.

“He was a shy, serious kid who hardly ate anything,” she tells us. “Gymnastics has always been his life. Even as a baby in the cot he’d be swinging from the bars. As he got older I asked if he wanted to go swimming or play baseball, but he had no interest whatsoever. Gymnastics was all he cared about.”

Kohei was influenced by his parents who were both competitive gymnasts during their youth. He joined the sports club they ran in Nagasaki at the age of three and spent much of his free time practicing on the trampoline. A notebook and a Pink Panther toy were used as tools to help him come up with new moves.

“I made line drawings of gymnastic elements I wanted to perform,” he says. “I would then adjust those images with the toy. Imagining the movements of the doll I was able to produce a variety of routines naturally.”

“He got that from an older friend at the gym,” continues Shuko. “He used to take it everywhere, which meant it got really dirty. A while ago I noticed it on his bed and it’d been washed. It’s one of his most treasured items.”

Speaking a mix of Japanese and English, Shuko comes across as a bubbly, slightly eccentric character. She goes around the world to watch her son and can often be heard screaming from the stands. “That embarrassed me back when I was a student, but now I’m a father I can appreciate it,” Kohei tells us.

“As a coach she’s always been very energetic and lively,” he says. “She thought out nutritious meals for me – even though I was a picky eater – and she was never strict. She realized it was important to develop my personality and give me freedom. Her teaching style wasn’t methodical and I think that’s reflected in the way I practice now.”

It was at his parents’ gym where Kohei first nurtured his gymnastic skills, but at 15 he decided it was time to leave his home in Nagasaki and move to the capital where he could train with idol Naoya Tsukahara. The youngster spent hours during his childhood studying videos of the man who helped Japan win a team gold at the 2004 Olympics.

“I really didn’t want my boy to leave, but Naoya was his hero so I was fighting a losing battle,” Shuko says. “On reflection it was a good decision because he made a lot of progress during that time. I remember watching him in his third year at high school and for the first time I thought to myself, ‘He’s actually pretty good.’ After that things started to accelerate.”

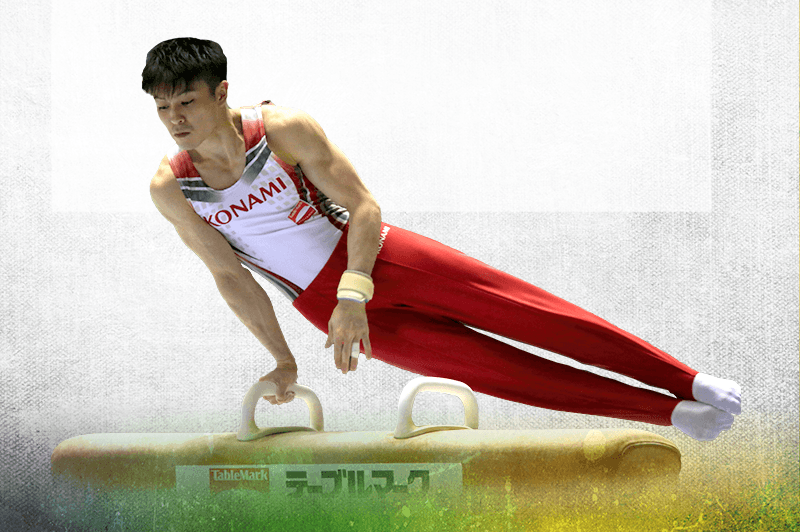

The Kitakyushu-born star made his international debut at 18 and then a year later qualified for the 2008 Olympics. He helped his country win a team silver in Beijing before becoming the first Japanese man in 24 years to finish on the podium in the all-around (AA) competition, finishing as the runner-up behind Yang Wei despite twice falling off the pommel horse. He hasn’t lost in the event since.

In the past eight years Kohei has won five Olympic medals – including one gold – and 10 world titles, six of which have come in the AA event. He usually finishes so far out in front that the rest of the field are effectively competing for second place.

Rivals have labeled him a “machine” and a “monster.” After winning a silver in the AA competition at last year’s World Championships, Cuba’s Manrique Larduet spoke about his “pride” at being able to compete with the Japanese gymnast, while 2014 runner-up Max Whitlock said it was “very special” to be standing alongside him on the podium.

According to his mother, it’s Kohei’s insatiable desire for perfection that gives him the edge. “He simply doesn’t stop,” she says. So has he become so dominant that she’s now able to relax when watching him?

“No way,” she responds immediately. “I still get so nervous. The competition’s always getting stronger. The other athletes are copying what Kohei does and as a result their scores are much closer.”

While recent World Championships back up her point (the margin of victory in the last two tournaments has been 1.492 and 1.634 points compared with 2.575 in 2009 and 3.101 in 2011), there is still a significant gap between him and the rest.

Opponents are coming up with routines to match him, but they don’t have the grace or the pointed-toe finish of the 5’4” (162.6 cm) superstar. It’s why so many regard “King Kohei” as the best of all time. The man himself, however, believes that title belongs to Vitaly Scherbo, the Belarusian gymnast who won an unprecedented six gold medals at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics.

“For me there’s no doubt that his performances were the greatest ever,” Kohei says. “They were elegant, perfect and got great scores. I want to make my routines ‘impressive’ like his, but he is Scherbo, and I’m Uchimura. I can’t surpass him. I can only be the best I can be.”

Scherbo’s feat in Barcelona is unlikely to ever be beaten or repeated. It’s undoubtedly the most impressive performance by a male gymnast in Olympic history, yet in terms of longevity Kohei Uchimura is the man who stands head and shoulders above everyone. To remain unbeaten for so long in such a physically demanding sport is testament to his character and ability.

Opponents in Rio know they’ll have to produce something special to beat him. He’s the red hot favorite in the AA competition and also fancies his chances of winning in at least one other discipline.

Individual success won’t be enough, though. It’s a team gold he truly craves. In the last two Olympics, Japan has finished second behind rivals China, but are going to Rio full of confidence after winning their first team world title for 37 years in Glasgow last October.

“Four years ago the judges initially had us down at fourth and my head just went blank,” he says. “I was stunned and my feelings didn’t change even when we moved up to second. I was angry with the performance.”

“Looking back I’m glad to have been on the podium with my teammates, but in Rio I hope it’ll be as champions. I want a team gold more than anything. In Japan everyone remembers (Hiroyuki) Tomita’s spectacular landing from the horizontal bars at the Athens Games to clinch the victory. It was a legendary team performance and that’s what we must strive for in Brazil.”

Restarting a Gymnastics Powerhouse

Japan has won 95 gymnastic medals at the Olympics, including 29 golds, placing the country third in the all-time list behind the Soviet Union and America. Twenty-four of those 29 golds came between 1960 and 1976. Sawao Kato led the way, picking up eight golds, three silvers and a bronze, making him the ninth most successful Olympian of all time. Four other male Japanese gymnasts from that period are in the top 100.

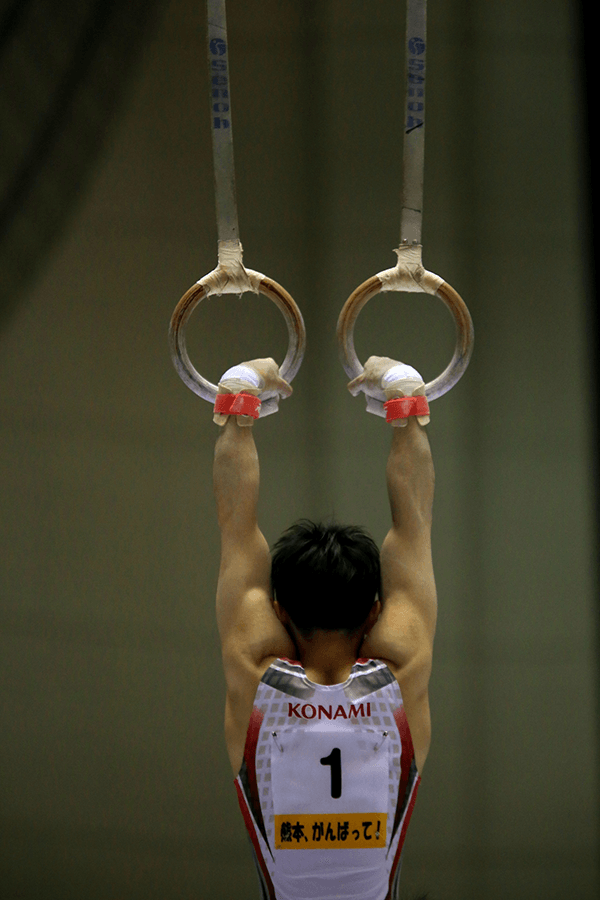

It was a golden era for the men’s team who won five consecutive Olympic titles. The most memorable triumph came at the Montreal Games in 1976 when Shun Fujimoto continued competing despite breaking his kneecap on the floor routine and remarkably went on to score 9.5 on the horse and a personal record 9.7 on the rings to help Japan retain the title.

In the 40 years that have passed, Japanese male gymnasts have added just four Olympic golds; however, there’s a strong feeling that the current crop could produce the country’s best results since Montreal. Kohei Uchimura and Ryohei Kato have already booked their places in the squad for Rio and are expected to be joined by the likes of Yusuke Tanaka, Kenzo Shirai and Kazuma Kaya, all of whom are capable of challenging for medals.

As for the women, Asuka Teramoto, Mai Murakami and Aiko Sugihara have looked strong during qualification. Japan is still waiting for its first female gymnastics Olympic champion.

Photos by Hiromi Ave