This winter sport is enjoying a global revival, and Fukushima’s powdery backcountry is the perfect place to try it.

Before the Tohoku earthquake of 2011, Fukushima was one of Japan’s best-kept surfing secrets. The long, jagged Pacific coastline offered a variety of breaks, and caught swell throughout the year. Since many coastal areas are now irreparably changed and some remain off limits, the best remaining surf spots in Fukushima are now on its snow-covered mountains.

Snowsurfing is the art of riding snow like a wave. Its roots can be traced to the origins of snowboarding, with early snowboards, like the Snurfer, being modeled after surfboards. As board design and technology advanced, the emphasis of mainstream snowboarding evolved from carves to airs and skate-style tricks, and the popularity of snowsurfing faded on the global scene. Nevertheless, the underground snowsurf movement has remained a force with carving purists, and has begun to regain popularity in the resorts and backcountry mountains of the world.

The feeling of riding a mountain of powder snow is much like the feeling of surfing an endless flowing wave, and Japan’s near endless supply of powder perfectly suits snowsurfing. My first experience of snowsurfing began with an early morning departure from Tokyo to the mountains of Fukushima Prefecture, which is bordered by the Pacific Ocean and the Japanese Alps. Our destination was Hinoemata, a small village tucked away in the mountainous Aizu region, located close to Oze. Fukushima doesn’t have the international acclaim enjoyed by Hakuba or Niseko, and Hinoemata doesn’t have the towering peaks of neighboring Niigata and Gunma, but this makes it all the more interesting. It’s like a secret surf spot hidden within a city. It will never be famous, but it will also never be crowded.

After a long drive we arrived at the parking lot near the base of the mountain where we met our guide Takayuki Hirano, and spotted the mini snowcat we would ride to access the backcountry. As if on cue, the snow that had been falling all morning began to clear up as we loaded our gear onto the side of the snowcat and crammed ourselves inside. The warm interior and quiet grins of everyone reminded me of an Indonesian boat ride I once took to one of the hundreds of breaks at that surf mecca. We felt a shared mix of nervousness and excitement as we gazed out the windows to witness the warm rays of sunshine piercing through the cold morning.

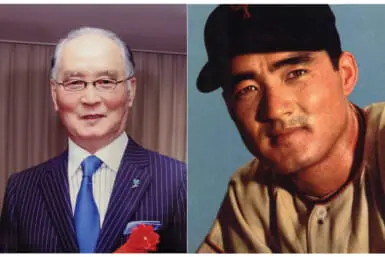

Dozing off in the warm cabin, I awoke 30 minutes later as we arrived at the lodge. In front were two snowmobiles with large rubber boats – like the ones used for white water rafting – tied behind them. Inside was a small repair shop and a wall lined with colorful boards that looked more like surfboards than snowboards. These funky boards were all made by Moss, the world’s oldest snowsurfing brand. More than 40 years ago, Moss founder Shinzo Tanuma had a dream to surf on snow. In 1971, he created the first Moss Snowstick prototype, which was made from urethane foam and fiberglass, much like a traditional surfboard. He test-rode the prototype at the Akakura Onsen ski resort in Niigata, and started a revolution.

The original Moss Snowsticks have been refined, with designs varying over the last four decades. The mix of tail shapes, board length, and nose width differs to match the rider’s desire to draw big lines and deep carves. I was quickly drawn to the Moss Quadstick model. The fat nose and swallow tail are similar in design to my favorite type of surfboard, and my mind raced with the possibilities. After swapping out my bindings I loaded the board into the rubber rafts with the rest of our group. As we made our way to the top of the mountain, the sun lit up the slopes, and the quiver of colorful Moss boards sticking out of the side of the boats struck a bright contrast against the pristine white snow.

The snowmobile and rafts followed a narrow, snow-covered, closed road that snaked up to the top of the mountain. The recent snow storm had completely blanketed the area in nearly a meter of fresh pow. The occasional street sign or steel rockslide barriers were the only clues that this road – which gives way to open valleys and powder-covered trees – was ever in use. After a few minutes Takayuki stopped the snowmobiles and attached water-ski tow ropes to the boats. For the remainder of the ride up we took turns towing behind the snowmobiles, carving off the snowbanks lining the side of the road like wakeboarders behind a boat.

Once at the top we unloaded our boards and gear from the boats and strapped in. The silence of the mountain was only broken by gentle laughter. Underneath the facemasks and scarves of the other riders there were big smiles as we glimpsed the sun glistening off the fresh powder. Everyone peered over the side of the road into the valley and mind-surfed the untouched terrain.

Lining up along the ridge line we peered over the edge. The etiquette for this trip is to drop in one by one to let each person enjoy their run. I watched as a rider shouted “Ittekimasu” and slid into the fresh powder between the trees, leaving an arch of spray after each turn. Anxiously I watched, knowing I was next. After a few minutes I dropped off onto the run. The wide nose on my Moss Snowstick sank into the soft powder, then rose up to plane as I gained speed. I was floating over an ocean of snow and flowing effortlessly between the trees. The endless wave of powder made me feel like I was surfing a perfect Mexican point break that never ends, and rekindled the stoke that only a surfer knows.

When I joined up with the rest of the group, the vibe was as if everyone had just caught the wave of their life. The mix of perfect conditions and equipment left an overwhelming feeling of accomplishment earned from taking the time to seek out a new place and try something different. When we eventually returned on the snowcat to the parking lot, we were exhausted but still smiling. To end things off, we took a short drive to the local onsen, where we soaked our tired bodies and swapped stories of our perfect day.

Words by Phil Luza