After almost three decades as the ceremonial figurehead of Japan, Emperor Akihito has been given permission to step down. The 83-year-old, who has undergone heart surgery and had treatment for prostate cancer, no longer feels he can carry out his duties properly. A one-off bill has been passed by the government allowing him to renounce the throne. It will be Japan’s first abdication in more than two centuries, with the baton being passed on to his son, Crown Prince Naruhito.

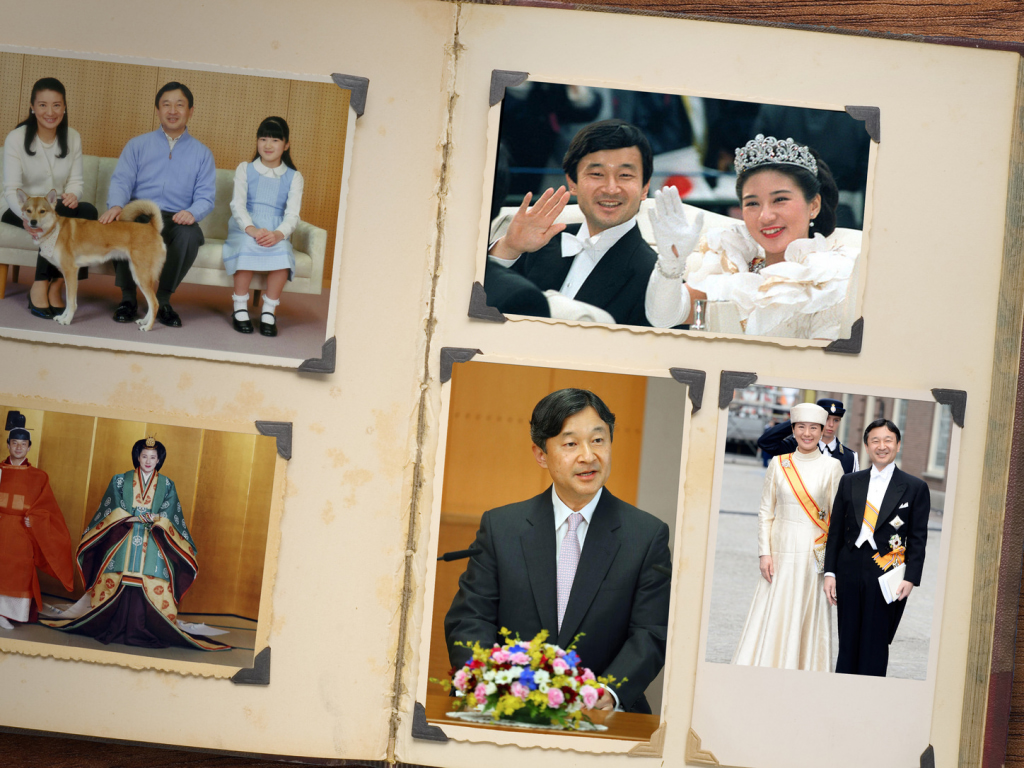

On May 1, 2019, Naruhito will become the 126th emperor in the world’s oldest hereditary monarchy, a line dating back to the 5th century. So, what do we know about the heir apparent to the Chrysanthemum Throne? Here’s a look at the life and times of the future emperor.

The Naru-chan Constitution

The eldest son of Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko, Naruhito was born in a makeshift hospital at the palace on February 23, 1960. His mother – the first commoner to marry into the imperial family – decided to raise Naruhito and his siblings, Prince Akishino and Sayako Kuroda, herself, even breastfeeding them. While that may not sound noteworthy, at the time it was considered significant as the everyday care of royal children had previously been the duty of wet nurses and maids.

When his parents were away Naruhito would be left with nannies who were given written instructions by Michiko on how to take care of him. He was allowed no more than one toy at a time and had to be hugged at least once a day. This list of rules was turned into a best-selling book titled Naru-chan Kenpo (The Naruhito Constitution) that’s still popular today.

From all accounts, Naruhito was said to have had a happy and relatively normal upbringing, especially when compared to his ancestors. His father allegedly gave him a hand-me-down uniform to wear to school and told teachers not to give him any special treatment. The young prince enjoyed watching baseball, hiking and skiing.

Clubbing, Pub Crawls, and Tea with the Queen

In 1983, a year after graduating from Gakushuin University, Naruhito decided to move to the UK where he did a master’s degree on the history of transportation on the River Thames at Oxford University’s Merton College. More important than his classroom studies, however, were the life lessons he learnt during his two years in Britain.

For the first time, the prince had to fend for himself and seemed to revel in it. In his book, The Thames and I: A Memoir of Two Years at Oxford, he wrote, “This had been a happy time for me – perhaps I should say the happiest time of my life.” The autobiographical account, whilst not exactly hard-hitting, gives a fascinating insight into the personal escapades of a man whose privacy is usually closely guarded.

“This had been a happy time for me – perhaps I should say the happiest time of my life”

Much of his first week in England was spent in the company of the royal family, including the Queen, who impressed him with her laid-back manner and the fact that she poured him a cup of tea herself. Shortly after, he moved into a shared dormitory in Oxford where he learnt how to iron and use the coin laundry machine, though his first attempt at the latter ended with him almost flooding the room.

One of his favorite pastimes was discussing music over a few pints. He even went on a few pub crawls. The prince apologizes to the British public for not getting to grips with the rules of cricket, but did participate in many British sports such as tennis and rowing. It was an exciting time for a man who, under normal circumstances, can barely move without asking for permission.

“I met the crown prince twice,” says social anthropologist Joy Hendry. “On the second occasion, I sat opposite his personal body guard who told me how much the prince loved being in Oxford because he could walk about in the streets and the local market where nobody recognized him, which made him feel free like any other student.”

Around the city Naruhito would usually wear jeans, much to the surprise of Japanese tourists. His casual attire got him turned away from a nightclub, yet that didn’t put him off. He went to a different club at a later date, dancing with girls until 2am. “Perhaps this was the first and last disco I would go to in my life,” he remarked.

In October 1985 Naruhito departed from the UK. “As the London scene gradually disappeared from view I realized that an important chapter in my life was over. A new page was opening, but I felt a large void in my heart, and as I stared out of the window of the plane I had a lump in my throat.”

In Pursuit of a Princess

Back in Japan, Naruhito’s activities were far more constricted, and being in his mid-twenties he was under pressure to find a bride. He could reportedly choose one himself, but she had to meet the approval of a committee of palace officials. The plan was to have him married off before reaching 30, yet despite numerous candidates being put forward the prince remained single at 32.

His first choice was Harvard graduate Masako Owada, whom he pursued for six years after they met at a banquet for the Duchess of Lugo in 1986. Coming from a wealthy family, she ticked most of the committee’s boxes: highly educated, multilingual and, crucially, slightly shorter than the prince.

One problem was the controversy surrounding her maternal grandfather, Yutaka Egashira. He was the former chairman of Chisso Corporation, a chemical company that dumped mercury-laden industrial waste into the bay off Minamata in Kyushu, leading to the onset of Minamata Disease. Thousands were affected by the neurological syndrome, which in extreme cases, led to insanity, paralysis and death. Though not directly involved in the scandal, Egashira’s association with Chisso was seen as potentially damaging for the imperial family.

Despite this, Naruhito was still determined to wed Masako. Unfortunately, she wasn’t so keen. Twice she turned down his proposals as it would mean giving up a budding career as a diplomat for the constrained life of a princess. Not one to give in, Naruhito tried a third time and finally got his wish.

“His Highness told me that ‘you may have many worries and anxieties about entering the imperial house, but I will do everything in my power to protect you as long as I live’”

Speaking at a press conference after their wedding in 1993, Crown Princess Masako said, “His Highness told me that ‘you may have many worries and anxieties about entering the imperial house, but I will do everything in my power to protect you as long as I live.’”

Despite the support of her husband, Masako has struggled with life as a royal. Under pressure to produce a male heir, she miscarried in 1999. Two years later Princess Aiko was born; however, as Japan operates under a system of agnatic primogeniture, this did little to solve the succession problem. It was all getting too much for the future empress.

Speaking to journalists in 2004, Naruhito said, “Princess Masako still faces ups and downs in terms of her health. She’s worked hard to adapt to the environment of the Imperial Household for the past decade, but from what I can see, she’s completely exhausted herself in trying to do so.”

It was announced that Masako was suffering from adjustment disorder, a mental condition brought on by stress, making it difficult for her to carry out official duties. The birth of Prince Hisahito – son of the crown prince’s brother and third in line for the throne – reduced some of the pressure. Her condition is said to have improved slightly in recent years, but public appearances remain sporadic. Whether that will change when she becomes empress remains to be seen.

As for Naruhito, this is a role he has been preparing for since childhood. His amiable father, ably supported by wife Michiko, is held in high regard for prioritizing disaster victims, championing the cause of marginalized people and attempting to reconcile with countries affected by Japan’s colonialism and wartime aggression. The hope is that his son will devote himself to the role of emperor in a similar fashion.