Mamiko Masumura’s art studio takes up her bedroom. She sleeps on the living room couch of the house she shares with her parents. She wakes up before they do so she isn’t underfoot.

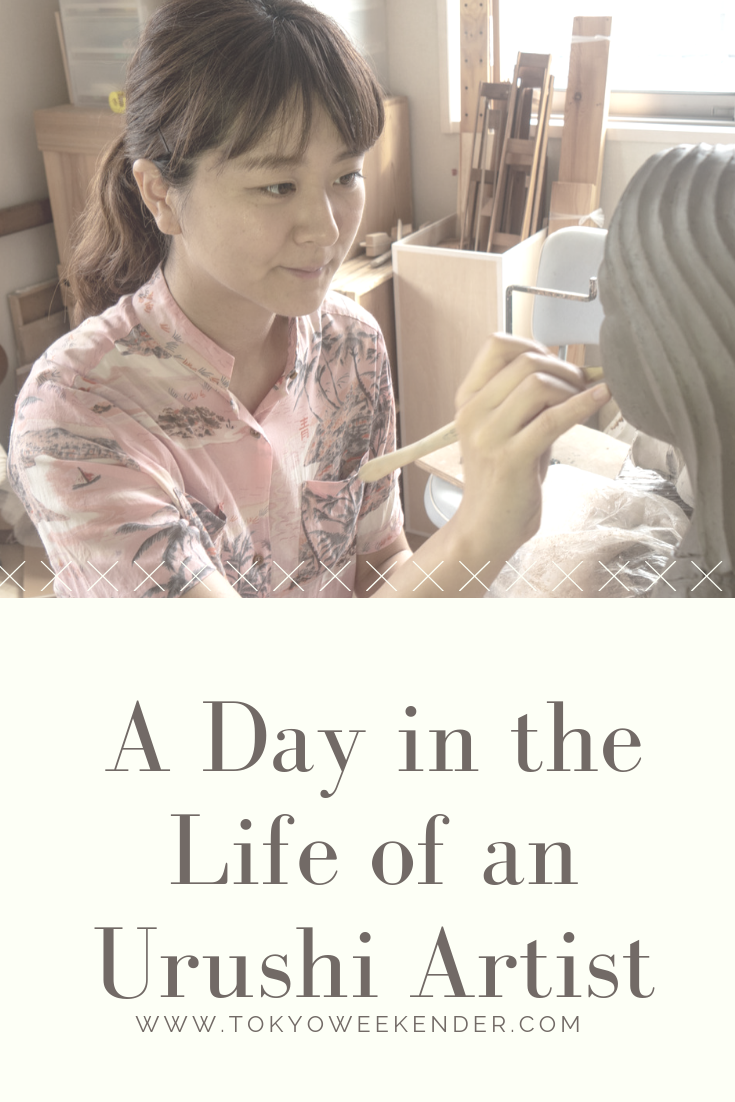

Natural light illuminates her small studio-slash-childhood bedroom. There is a table covered with cacti, her latest muse. Brushes made from human hair and handmade wooden knives and spatulas are neatly arranged across the top of her workbench, as are a few empty beer bottles.

The studio of her father, urushi artist and living national treasure Kiichiro Masumura, is in the room next door. Mamiko grew up in this house, which is in Kasukabe, Saitama, watching her father at work. Filled with rustic handmade bookshelves, cabinets and wooden tools, it is in her father’s studio that Mamiko says she is most comfortable working on her art.

Urushi lacquerware art arrived in Hokkaido around 5000 BCE, during the Jomon period. Traditional Japanese urushi involves applying black tar-like sap from poison oak trees (containing the same noxious chemical as poison ivy) to bowls, boxes or other objects, which are then typically adorned with gold or silver powder.

Mamiko blends vibrant, colorful pigments with urushi that distinguishes her pop-like, contemporary art from more traditional styles. The 31-year-old, whose late grandfather was also a living national treasure, is excited to show a sample of urushi sap she sourced from North Korea. Light in tone, Mamiko hopes it will enhance the coloration.

With a tentatively scheduled October exhibition in the Netherlands and two exhibitions at Takashimaya department stores in Tokyo and Osaka coming up in 2019, Mamiko is busy producing her signature urushi sculptures of feminine figurines and vegetative wall hangings when we visit. Taking a break, she explains the daily routine of an up-and-coming urushi artist.

What is a typical day like?

I work from the time I wake up until the time I go to bed. The first thing I do is water the plants in my garden. I like the cactus’ unique form. It is a form whose sole function is to store water. I watch the plants and observe how they grow, their condition, and the bugs and worms. I like watching caterpillars. Yesterday the caterpillar I had been watching turned into a cocoon. It is a tiny thing, but I enjoy it. Then I have coffee, and then I start working. I usually don’t make specific concrete plans, like today I am going to do step one, step two, step three. I just start working. Yesterday I finished at 3am. I don’t have a specific finish time. I finish when I am satisfied with my work for the day.

What materials do you use?

I use mud clay for the base. This clay is used for traditional Japanese clay sculptures, such as those you see in temples or shrines. Once I finish sculpting the piece, I cast the clay with material called kata, and it becomes a plaster mold. Once the plaster dries, you remove the clay cast. Then I wrap the plaster mold with layers of linen fabric adhered with urushi. Once the fabric dries, you soak the mold and the fabric in water, which makes them separate. The fabric mold is very light and strong. I use polishing stones to smooth the surface. Then I use a mix of urushi and special mud that comes from a fossilized rock. A lot of history, and ancient spirits, live in this mud. This mud comes from Ishikawa Prefecture. The urushi trees are in Ibaraki and Iwate. I mix the mud and urushi and apply it to the piece. I use tools to polish it again, and then apply urushi again, and polish it again. Again and again. Maybe 20 or 30 times. I don’t count, I just continue until I am satisfied.

Why did you choose this job?

I made the decision when I was a child. My grandfather and father were urushi artists. My grandfather passed away when I was little, so I never had the chance to watch him work. As for my father, I have been watching him since I was a kid. That entire tableau seemed like fun to me. I also like to make things with my hands. I thought, maybe I will be an artist.

How old were you when you started to learn urushi?

Second grade. It was fun. I was watching a television program about a Chanel fashion show, and I was so impressed that I told my parents I want something from Chanel. My father told me, then why don’t we make a Chanel ruler? So he cut a long piece of plastic and carved little centimeter marks like a ruler, and he had me engrave Chanel’s logo in the plastic and coat it with gold powder, a traditional urushi technique called maki-e. This was my first urushi piece.

What lessons did you learn from your father?

He often told me, just move your hands without thinking. Don’t think, just move your hands first. Even though my father has told me that so many times, I still spend most of my time thinking. I spend a month on research only before I start a new piece. My father has a personal view that an urushi artist should make all of their tools by hand. He sometimes spends more time making tools than making urushi.

When did you develop your personal style of urushi?

I started this style when I was in university. I wanted to express the same feeling I have when I walk in nature, or the mountains or seas, or the feeling of comfortable wind. I wanted to express that feeling through someone else. That was my first motivation to create a human figure. I wanted to reflect that feeling through a figure of a girl.

Traditional urushi is brown, black or red. Why did you start using pastels?

Recently some artists have started to use colored urushi, but when I was in university, I didn’t see anyone using it. When I was a freshman, I saw my senior using white-colored urushi, and I was impressed with the color. I thought if we have white urushi, then why can’t we use other colors? I spent a lot of time blending and mixing to make these beautiful colors. It was very difficult. The natural color of urushi is dark brown. If you mix it with color pigments, it always comes out in a different tone of brown. I tested a lot of different urushi from different locations of Japan. Ibaraki, Iwate, Miyagi, Nagano, etc. Ibaraki urushi has the most transparency. The transparency enhances the brightness of the color pigment

“A lot of history, and ancient spirits live in this mud”

What’s the best part about your job?

I enjoy how the works make a connection, or bond, between myself and other people. Of course everyone has different opinions or comments about my work, but it is interesting that there are some common feelings. People say they feel a sense of nostalgia. That natsukashii feeling, the sense of reminiscence. I thought Japanese people would make that comment, but I was surprised to hear Dutch people and American people say the same thing.

What’s the hardest part?

The hardest thing is creating something from scratch. It’s not easy, but I enjoy moving my hands, creating an object. Before that, I need to think about what I can create. That process is the hardest part, but at the same time, it is the most interesting. I hate deadlines the most. But the deadlines make me hustle.

Without deadlines, I might not complete anything.

More info at www.mamikomasumura.com