It was a chilly autumn evening in November 2017 when Adam Isfendiyar gathered together a couple of cardboard boxes, some masking tape, a sleeping bag and other overnight supplies and headed to a bridge in Shinjuku. He was going to spend four nights there, sleeping under the bridge next to Koisou Matsuyoshi.

At the time, Isfendiyar hadn’t quite fleshed out what he wanted to do with the experience. He knew he wanted to document Matsuyoshi’s world as a homeless person in Tokyo – a world that so many who visit the city never even see – and he knew that, in order to do this properly and to be able to convey the emotion of the subject, he needed to immerse himself in this world. What he didn’t know was that over the next few months the project would evolve to become a body of work that captures not only intimate moments of Matsuyoshi’s life on the streets, but also the heartwarming story of a unique dance group whose members are all homeless.

“When I first came to Tokyo, I once saw a group of old men in the park, with all their belongings stacked up neatly next to them in trolleys. What struck me was that they seemed quite content. They didn’t seem like men in despair,” says the British-born photographer. “I also noticed that, unlike in London, you don’t really see homeless people on the streets in Tokyo. And if you do, they’re not begging; they don’t seem to have drug problems or anything like that. A few Japanese people told me that many of the homeless here actually have some monetary savings and have just chosen to opt out of society. So I became intrigued to find out more about them and their stories.”

“A few Japanese people told me that many of the homeless here actually have some monetary savings and have just chosen to opt out of society”

Isfendiyar was working as a teacher and training as an acupuncturist, but he was looking for a change in career, hoping to move into a more creative field. He had just started experimenting with photography when, one day on his way to work, he passed by a man selling The Big Issue. “I stopped and asked if I could take his photo. Turned out he spoke near fluent English. He told me his name was Matsuyoshi-san.”

After that chance encounter, the two men struck up a kind of friendship, with the photographer stopping to chat every so often, and the homeless Japanese man sharing details about his life, showing Isfendiyar the spot under the bridge where he sleeps each night, and telling him about the dance group to which he belongs.

“He told me he was in his late sixties and he felt that his options were very limited. He used to live in London for 10 years, but when he returned to Japan he found it tough readapting to Japanese society and working life, and so he chose not to be part of it. He isn’t claiming benefits because, in Japan, the government will only pay benefits to the homeless after they’ve contacted your family and asked if anyone can support you. Matsuyoshi-san doesn’t want his family contacted, not because he’s had a falling out with them, but because he doesn’t want to be a burden on them.”

Isfendiyar pauses to take a pensive sip of peppermint tea, before adding, “He’s got a lot of pride. Almost too much pride, I think.”

It was a few weeks later that the photographer arrived, box in hand, to spend a few nights alongside his friend. “In fact, he had made a new box for me,” says Isfendiyar with a chuckle. “He’d taped it up neatly and put tarpaulin over the top for shelter. He’s really such a giving person.”

“It was the noise that affected me the most … It’s such a weird environment, being in a box but hearing the city around you. It’s very disorientating”

In describing the experience, Isfendiyar’s sensitivity towards Matsuyoshi is evident. While he shares some very practical details about sleeping on the street (“It was the noise that affected me the most … It’s such a weird environment, being in a box but hearing the city around you. It’s very disorientating”), he also expresses concern at having to view the man who had become a friend as a photography subject – a “thing.” It’s clear he took great pains to remain respectful and not be too intrusive.

During those five days and four nights spent living with Matsuyoshi, the photographer observed his daily routine – the nights spent under the bridge, the time spent at the public showers where he could get a 10-minute wash for a couple of hundred yen, the hours spent selling The Big Issue, and, perhaps most significantly, the evenings he attended the Sokerissa dance classes.

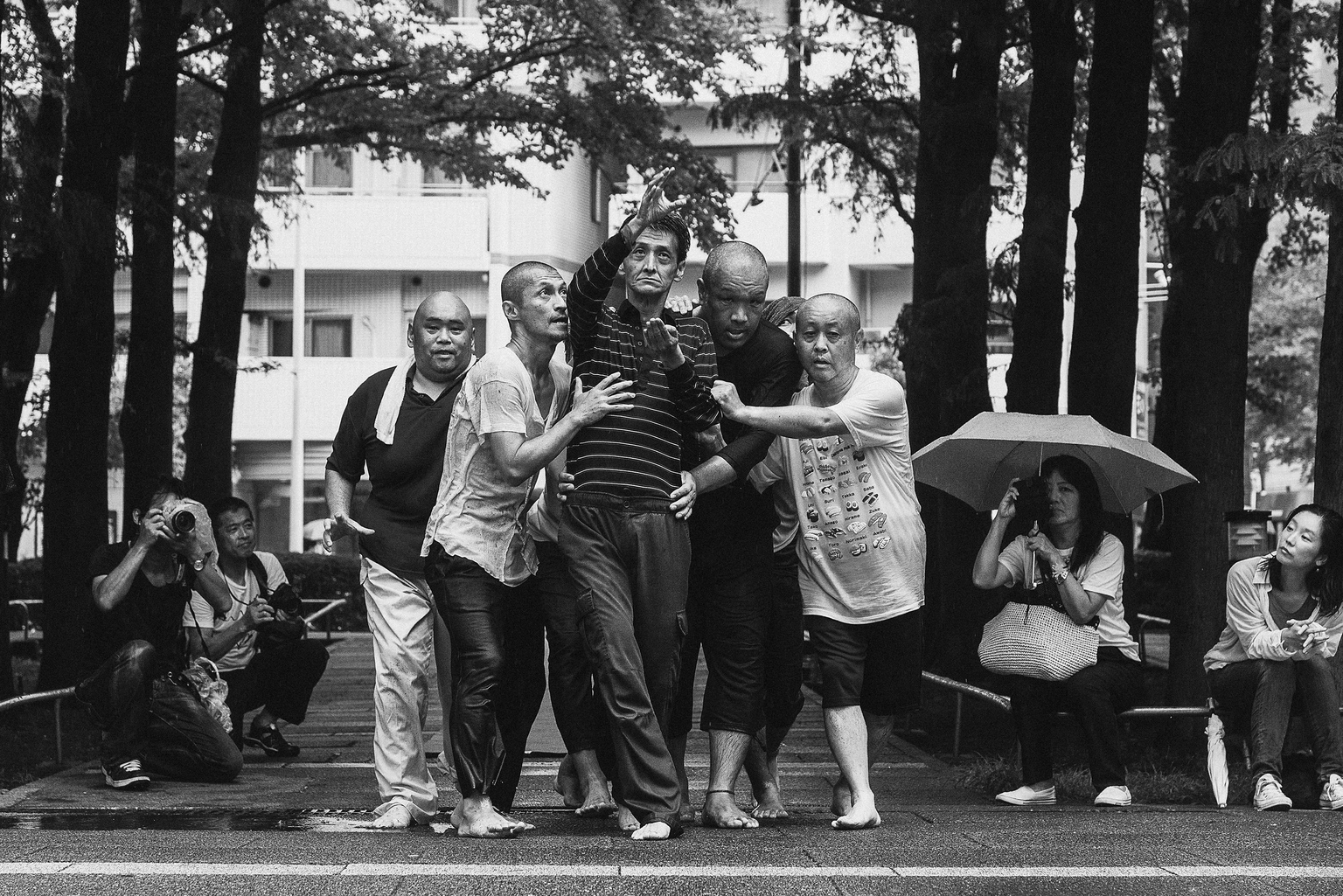

Founded in 2005 by professional dancer and choreographer Yuki Aoki, Sokerissa invites homeless participants to join regular rehearsals and to perform in public both in Japan and overseas. With help from various organizations, including UK-based project With One Voice, the dancers have traveled as far as Brazil for performances. Currently, they are crowdfunding on Kickstarter with the aim of putting on a show in Manchester, UK. Taking their name from the Japanese phrase “sore ike” meaning “step forward,” the group has built a reputation as a social reintegration program for socially vulnerable people.

The first time Isfendiyar went to watch one of their training sessions at a community center in Yotsuya, he says it was hard to understand what was going on. “They would play music and walk around, and it looked like it was a lot of free movement.”

“He would ask them to embody, for example, the sun or the color red or autumn leaves”

He decided to continue observing and over a period of four months regularly returned to the classes, photographing Matsuyoshi and the other dancers, and studying their movements. Each session, he explains, starts off with a warmup. This includes stretching after which Aoki leads the dancers through imagination exercises. “He would ask them to embody, for example, the sun or the color red or autumn leaves, and they would try to interpret that. Afterwards, they practice a set routine for about an hour.” When it comes to their public shows, the group usually first performs a choreographed dance, followed by solo interpretive dances they’ve created themselves based on words or poetry provided by Aoki.

“You know, if you tell people, oh we’re going to watch homeless dancers, most people’s first impression would be, ‘I’m going to have to grin and bear it,’” says Isfendiyar with a gentle laugh. “But from my experience and from most people I know who’ve seen them, you get sucked into it. There’s a lot of emotion. They really take it seriously and are very good at what they do. And at the end of it, they’re the stars of the show.”

For all the men involved, Sokerissa has given them a sense of community, identity and purpose. The group feels like a family to them, explains Isfendiyar. When talking about the changes he witnessed in the men, he frequently mentions how their self-confidence improved. For Matsuyoshi specifically, being part of Sokerissa has given him a sense of usefulness. “He told me that in the past he ran away from things. He has regrets and never really got stuck into anything and seen the fruits of his labor. The dancing has allowed him to focus his energy on something purposeful.”

Isfendiyar’s gritty black and white images may not immediately convey the more positive side of the homeless man’s story. Instead, they are filled with layered and undeniable emotion, conveying all of the dark and all of the light of Matsuyoshi’s world. A world that so many who visit Tokyo never even see.

To support Sokerissa’s crowdfunding campaign, go to hyperurl.co/Sokerissa

To view more of Adam Isfendiyar’s work, go to www.adamisfendiyar.com