Japan’s vending machines offer a cornucopia of treats from ice cream and corn chowder to dashi stock and the infamous – but illegal – used women’s panties. Although Japan is home to some of the world’s most unusual vending machines, it is the standard drinks machine that has experienced unparalleled success.

Boasting one machine for every 29 people, Japan has the highest density of vending machines in the world. They can regularly be found grouped together in twos or threes on the streets, even in quiet residential areas. The machines are directly in front of shops, on private driveways, inside parks and appear to sprout from Japan’s streets like giant electronically powered weeds.

Dispensed Across Japan

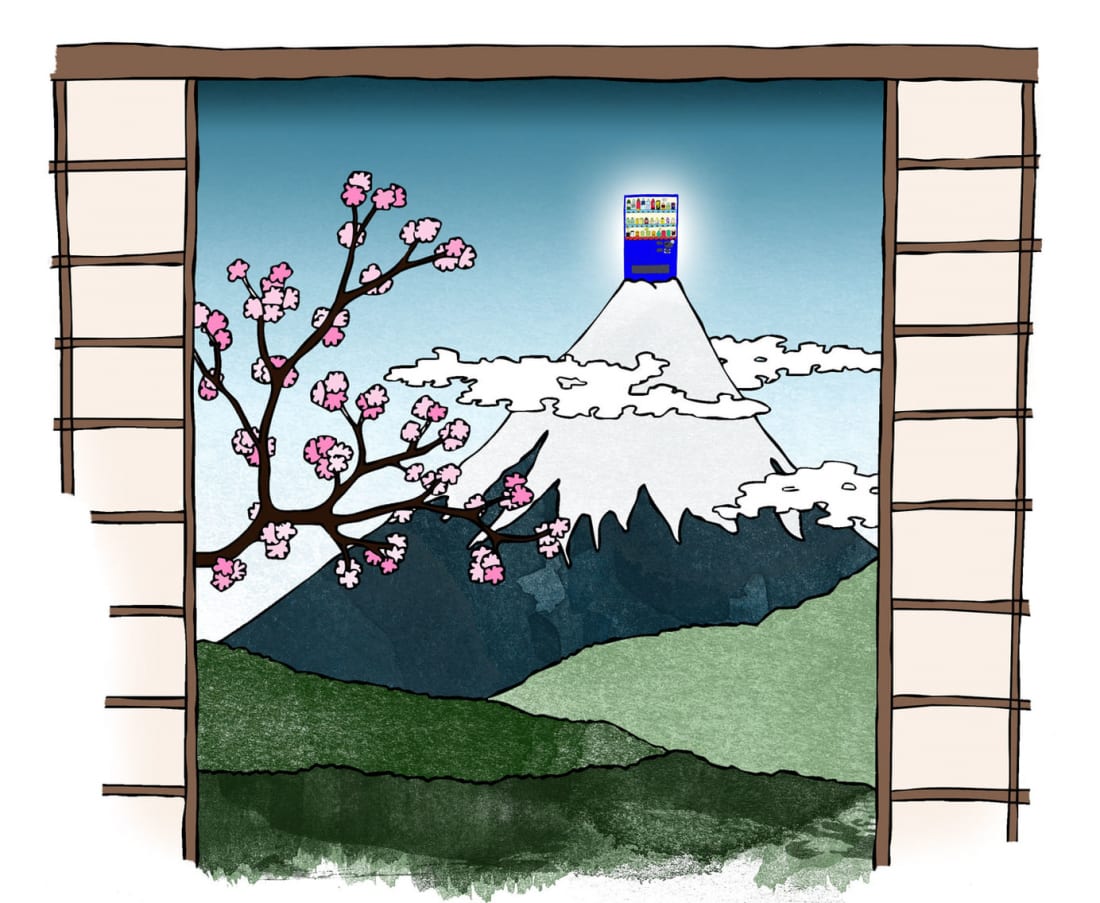

Surprisingly this phenomenon is not isolated to just Tokyo, or even Japan’s major cities. Vending machines can still be found in rural areas, to the point that you can even use one to reward yourself with a drink upon reaching the summit of Mount Fuji.

Is the undeniably successful glow of the Japanese vending machine just a result of good marketing and fluorescent lighting, or does it represent something deeper about contemporary life in Japan?

To those of us who have grown up in Western culture, the vending machine appears to embody a range of problems associated with modern society – our need for instant gratification, the production of single-use plastic, loss of genuine human contact and unemployment due to automation. Rather than be wary of automation, Japan’s fascination and trust in technology has created a unique consumer market that has allowed the vending machine industry to flourish. In Japan there is no uneasiness felt in buying from a machine, and with unemployment rates as low as 2.4 percent, there’s not the same anxiety towards automation that exists in countries with higher levels of unemployment.

Inspiring Tokyo Entrepreneurs

In Japan anyone can own a vending machine and while many are managed by large drinks companies such as Coca Cola and Asahi, there are also those that are independently owned and stocked by individuals who have chosen to invest in Japan’s unique vending machine market. The owners choose what products they want to sell and can then maintain and replenish their vending machines themselves.

A huge advantage of independently stocked vending machines is the variety of products available and with that, competition. If you’re not satisfied with what’s offered in one machine there is more than likely a completely different selection available nearby. The same can’t be said for the alternative to vending machines – convenience stores, which all tend to offer similar products.

Independent vending machines are allowing people to invest in the drinks market without the risk and financial burden that comes with opening a store and recruiting employees. This is especially relevant in Japan’s cities where the high population density is matched by equally high land prices.

Earning Profit One Coin at a Time

Vending machines allow sellers to access the densely populated areas of Japan without having to spend a fortune on retail space. When we consider the existence of independent owners, we no longer need to see vending machines as soulless metal boxes. Just because we cannot see the person behind the machine, does not mean our purchase is any more inhumane than buying from the large convenience store chains.

While Japan’s vending machines are undeniably plentiful at 4.3 million (the same population of Rome), are they actually making a profit? While some make more money than others due to product choice and machine location, it’s easy to back up their success with annual sales being recorded at over ¥7 trillion.

Japan’s vending machines are continuing to shape consumer trends while bringing distinctive blocks of fluorescently lit color to the streets. Whether you feel they represent convenience, good marketing, comfort or pure laziness, they are now as distinctive as London’s red telephone boxes and have undeniably earned their place as an iconic feature of the modern Japanese landscape.

Illustrations by Eleanor Hall