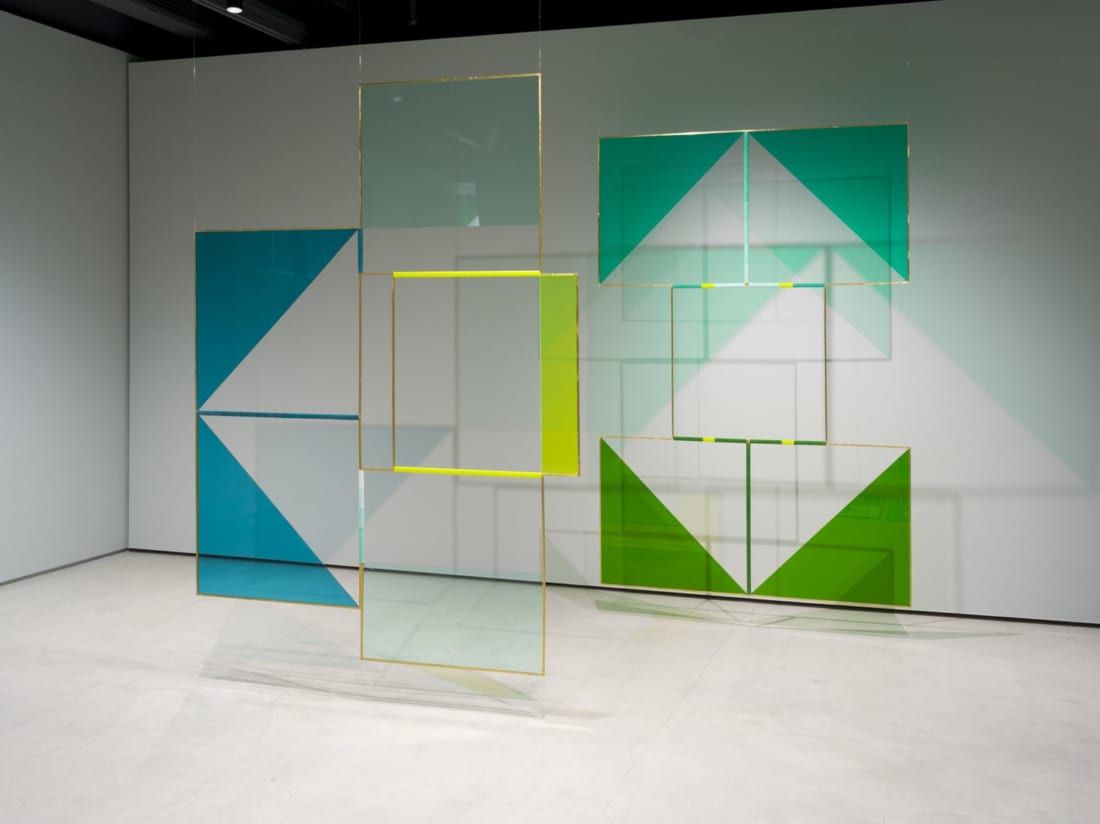

Courtesy of THE CLUB | Photo by KEI OKANO

With two brass bracelets dangling from her wrists, Mexican artist Claudia Peña Salinas flips through her well-worn scrapbook. She points to illustrations based on The Tale of the Genji. She pulls out square samples of Plexiglas and snippets of cotton thread dyed with textile ink in varying shades of green and blue.

For the past month, Peña Salinas catalogued her thoughts and inspirations in this notebook at a lodge in the mountains of Nagano, plotting her art installation titled Atlpan, now on exhibit at THE CLUB gallery at GINZA SIX.

“It’s just in your head for so long, and then to see it physically is the most rewarding time,” says Peña Salinas, a few days before the launch of her first exhibition in Asia.

The installation combines sculpture, painting, photography and video and the collective of images, stories and myths Peña Salinas has gathered through her studies and world travels. Much of her work involves wordplay, and the exhibition title, Atlpan, combines the Nahuatl word for water, “atl,” with the prefix for place, “pan.”

Water, and the lack of clean water, in her homeland of Mexico is a source of inspiration for Peña Salinas’ work, and since 2013 her installations have been informed by the Aztec god of rain, Tlaloc, and his female counterpart, the water deity Chalchiuhtlicue. The duo reins over the paradise kingdom of Tlalocan.

“I thought it was fitting that Japan is also a place of water. So here we are creating Tlalocan in Japan,” says Peña Salinas. “One of the things that the exhibition does is to pique the interest into this other culture…. The other, maybe more important, is [for people] to feel themselves in the space. Feel the space. Appreciate other things.”

Claudia Peña Salinas

The four hanging pieces were crafted using brass frames and Plexiglas adhered by natural cotton string dyed in the colors of jade and turquoise. These colors are associated with Tlaloc and Chalchiuhtlicue, whose name is commonly interpreted as “she of the jade skirt.”

Prior to arriving in Japan, Peña Salinas studied original Japanese illustrations of The Tale of the Genji in New York, and she was fascinated by traditional Japanese artists’ use of partitions to tell separate stories through a bird’s eye view. She designed the installation’s four wall hangings to act as shoji sliding doors, with the Plexiglas replacing the washi rice paper.

While The Tale of the Genji illustrations initially inspired the form of the installation, it was another Japanese folklore, The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, that helps tell the story of Atlpan. Peña Salinas says the myth is essentially the world’s first science-fiction tale, as it tells the story of a girl who arrives on earth from the moon, and lives with a bamboo cutter before returning to the heavens.

“I am here working with Chalchiuhtlicue, a strong female side of these two water deities, and the main stone of Chalchiuhtlicue was found next to the moon pyramid – one hour away from Mexico City,” says Peña Salinas, who studied the moon pyramid first-hand during a residency with Arizona State University. “I was looking at these stories and I was interested that Japan has more of a connection to the sun. But what about the moon?”

Courtesy of THE CLUB | Photo by KEI OKANO

While much of the preparation for the installation was conducted prior to her arrival in Tokyo, Peña Salinas wanted to source the four rocks that would serve as the pyramid-like centerpieces of her floor sculpture from Japan. Immediately after her arrival in Tokyo last August she was whisked away to Nagano, where she lived in the mountains for a month, sifting through slate stones in a nearby waterfall, mostly in the mist and rain.

“All the objects are always linked to the deities through the color or the site having something to do with water,” she says. “It was fitting that everywhere I would go it was just pouring rain.”

The sculpture consists of four multi-colored squares formed by textile patterns. The design is that of the traditional Mexican heirloom called a God’s Eye. When a baby is born, the skull is fragile and the most vulnerable spot is a soft indentation on the back of the head. The God’s Eye is hung on the wall for the first five years of life as a protection amulet. Some believe the object allows one to see beyond the physical world.

“[In school], we learn about Aztecs but we don’t learn the details,” says Peña Salinas. “We certainly learn about Christopher Columbus and the conquistadors. So presenting this work in Mexico has been interesting. The audience that should know the stories come out and say, ‘Thank you, I had no idea about our own history.’”

Courtesy of THE CLUB | Photo by KEI OKANO

Peña Salinas, 43, grew up playing in nature and streams in a small Mexican town of about 200 people near the Texas border. At age 10 her family moved to Chicago where she graduated from the Art Institute of Chicago. She has lived in New York City since 1999, and in the beginning she says she spent 12 hours a day in her studio creating abstract, minimalist paintings, not wanting to reveal her gender, heritage or personal story through art.

She gravitated toward installations and started taking photographs of New York City during long walks. She enjoyed the time outside the studio. Her research on a project involving gender roles in use of color, particularly the iconic paintings The Blue Boy and Pinkie, took her to Mexico. There she was reintroduced to Aztec culture and the mythology of the two water deities. Her works have since appeared in Mexico, Puerto Rico and New York, including The Whitney Museum of American Art.

“Somehow you can’t avoid talking about yourself. The stories of who I am and where I come from, came only in the last six, seven years,” says Peña Salinas. “In the end you just can’t escape it. Hopefully you have matured and you can actually say something about it.”