Canoeing doesn’t come up often in conversation. Thus my excitement was bubbling over as I sat in an Old Town fiberglass canoe in the middle of Lake Towada in Aomori Prefecture and my paddle mate was forced to listen to me babble about canoeing for an hour.

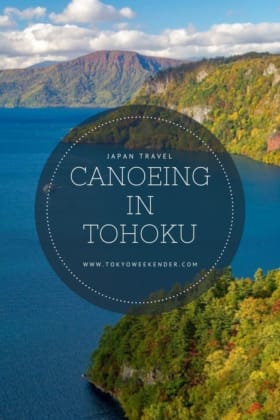

Lake Towada – the largest crater lake on Japan’s main island of Honshu – is the same size as Manhattan Island. Our nature guide with Towadako Guidehouse KAI, Yasuhiro Ota, tells us it takes four days to paddle the entire circumference of the lake.

The bespectacled Ota, lean with a bright smile and suntanned face, grew up canoeing and kayaking on Lake Towada. In addition to canoe tours he leads a “rambling tour” – or a nature course in which hikers explore every inch of the craggy hills surrounding the lake.

On this late October day the rolling landscape is covered in birch, maple and Japanese pin oak trees all decked out in blazing reds, yellows and oranges – brilliant foliage that makes Lake Towada a popular fall destination. Ota points out a spot where the ridgeline drops abruptly into a jagged cliff – a rock formation locals say looks like a whale.

Lake Towada | Photo by Koji Nishikawa

Before our crew arrived at Lake Towada, we were informed the conditions might be too windy for canoeing. As the powers that be studied the environs, us visitors stood watching the choppy waters lap at the rocky shore.

The scene took me back 20 years ago, when I was the canoe guide perched on a lakeshore at the Boundary Waters of Minnesota, observing the turbulent waters. That time we had no choice but to launch our canoes into the lake. It was the only way to reach safety.

Minnesota is known as the Land of 10,000 Lakes for a reason. Millenia ago the receding glaciers left pockets of water behind. The area that stretches deep into Canada is preserved as a primitive wilderness area, and the only way to access the pristine lakes is by canoe or floatplane.

Lake Towada | Photo by Koji Nishikawa

I first visited the Boundary Waters with my scout troop at the age of 12. For 10 days we canoed from lake to lake, camping at established campsites on the lakeshores. When we reached the end of one lake, we unpacked your canoes and hauled our equipment along the same trails used by the Native Americans and French voyageurs centuries ago.

As pre-teens we were most excited about the prospect of pooping in the woods. The Canadian side of the Boundary Waters has no latrines. We giggled at the thought of squatting over a dirt hole dug with the orange hand trowel. At night we shared tips – “lean up against the log, don’t hang your cheeks over the edge.”

The second time I visited the Boundary Waters was at age 18 with my father shortly after I dropped out of university. We didn’t talk much, but he did teach me how to drink whiskey from a flask – just take a sip and hold it under your tongue for 10 seconds to let the vapors evaporate directly into your brain.

It was this trip that inspired me to apply for a job as a canoe guide in the summer of 1999. Lost in the woods a bit after high school, I found the experience of guiding teenagers through the wilderness provided the direction and motivation needed to get back on life’s straight path.

I remember listening to the eerie hoot of the loon at night, followed by the hoard of mosquitoes descending directly overhead. I remember hearing a crash in the woods, and then the galloping hoofsteps of an unseen moose. There was the night a black bear and her cub circled our camp as we cooked a pot of beef stew over a Whisperlite stove.

Then the day of July 4 we were hit by a derecho – a rare, straight-line windstorm exceeding hurricane force. Because of the rocky ground surface, the roots of the black pines grew shallow, and they toppled over with ease. The derecho knocked over more trees than the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption. We were lucky that our crew was small, and we crouched in a hole created by a large, uprooted tree. We covered ourselves with a blue tarp, and sang Kumbaya.

When it was over the forest was nothing but fallen timber. We found our canoes swamped at the bottom of the lake. One tent was destroyed. We patched up the two tents that were salvageable and barely slept through that night’s thunderstorm.

The next day we used a handsaw to clear away trails covered in fallen timber. We slid canoes over piles of logs. When we reached the final lake, the wind picked up. Another storm was coming. We loaded into the canoes and fought against the headwind and waves, inching forward one stroke at a time to reach base camp.

Lake Towada | Photo by Koji Nishikawa

Standing on the shore of Lake Towada drudged up these memories. Ota and his merry band of canoe guides led us through safety instructions and basic paddling lessons. They asked if anyone had ever capsized a canoe. “Many times,” I said.

By the time they pushed us off, the waves had calmed. The canoes glided through the water. Through muscle memory my J-stroke came back to me and we held the canoe’s trajectory in a straight line, taking in the beautiful surrounding nature, and sharing stories.

I told my canoe mate about how I left my glasses at the top of a three-story-high rock face in the Boundary Waters and after retrieving them realized the quickest way down was to leap to the waters below.

I told him about the chainsmoker who drenched his last pack of cigarettes after deciding to navigate the rapids rather than carry his canoe down another portage trail. There was the day the crew caught 30 smallmouth bass after I told them, “There’s no fish in that lake.”

Canoeing at Lake Towada allowed me to share old memories, and create new ones to share the next time it comes up in conversation.

Lake Towada | Photo by Koji Nishikawa