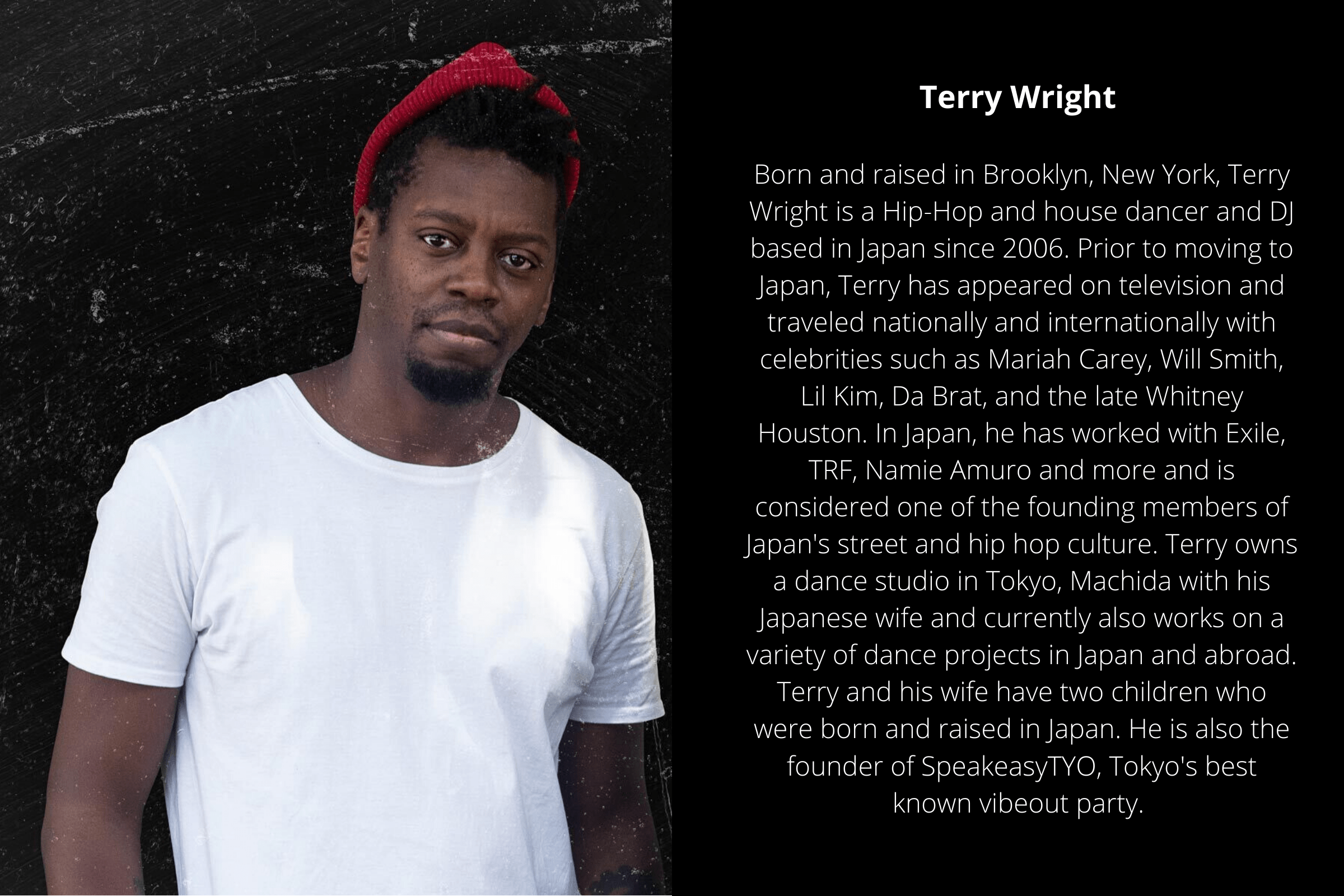

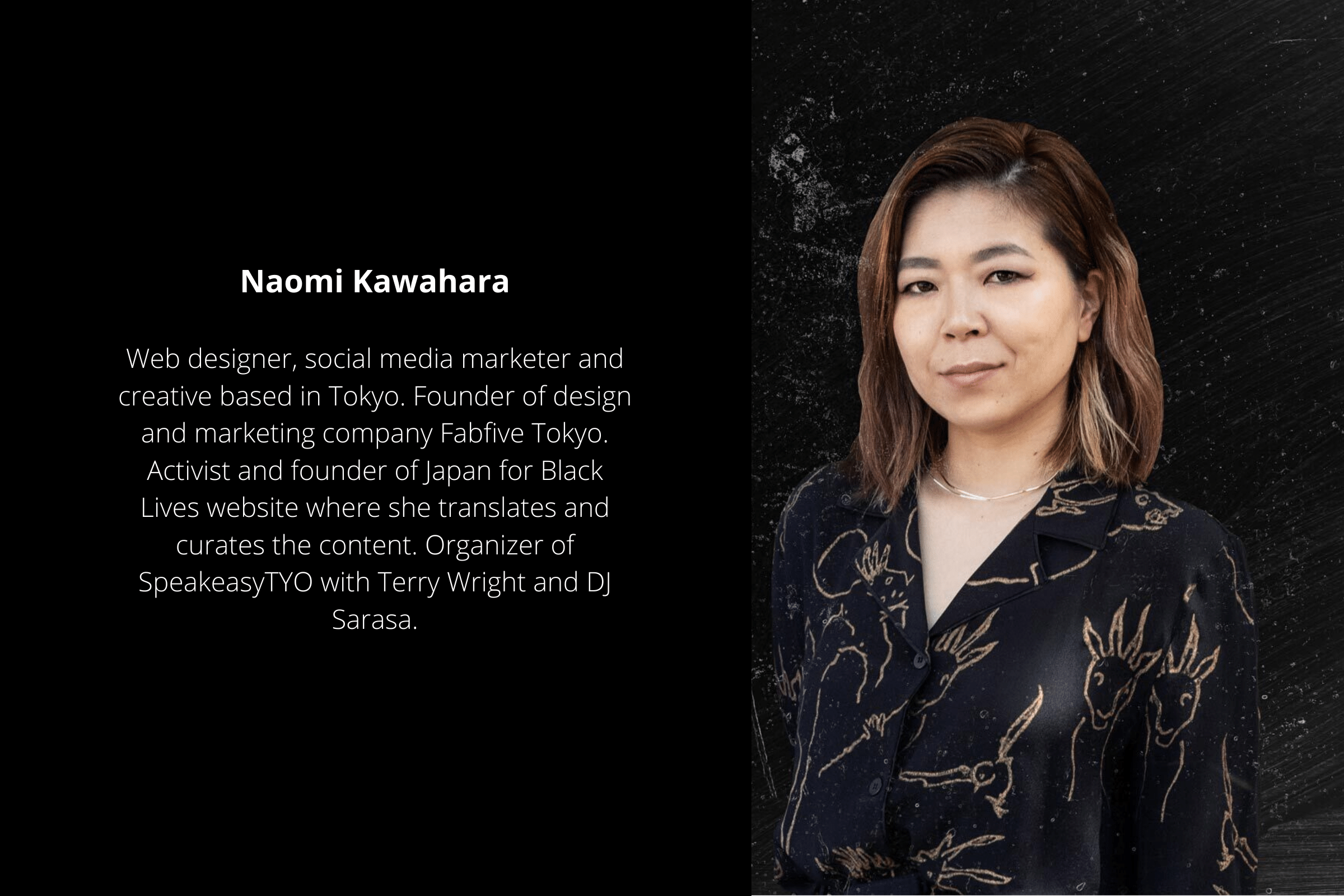

In the aftermath of the brutal death of George Floyd, on the other side of the Pacific ocean, Terry Wright, a Japan-based dancer and Naomi Kawahara, a Japanese web creative, instantly knew that this was the loudest wake-up call against global racism. They hoped that it was only a matter of time before Japan would speak up, addressing its own issues with racism. But days would pass and the silence became evident. Occasional news reports spotlighted protests happening abroad, but the narrative was clear: this was a foreign and very distant phenomenon. While the world was burning, Japan chose to be conveniently unaware of topics that required discussions.

“I couldn’t sit and watch this happening,” Naomi tells Tokyo Weekender in a recent interview. Japan had to wake up — and the marches happening in Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya and other parts of the country, where signs appealed that racism happens in Japan too and that Black Lives Matter is not only an American problem, were just some of the many proofs of that.

The two were quick to start working. A week from Floyd’s death, Terry organized Japan’s (at the time) first online bilingual panel discussion to discuss the recent events and talk about how racism influenced black culture and music — a field that he, as one of Japan’s most prominent foreign dance choreographers — takes to the heart. The discussion during the event, however, although successful in attracting some attention from Japan, was not sufficient. The duo’s next step was to strengthen their Japan For Black Lives website, a newly-launched well of information in Japanese that delves into digesting popular videos, social media posts, movies, songs and historical speeches on racism that can inspire Japan to understand the core of what it means to live as a black person — in the US, in Japan. Everywhere.

Tokyo Weekender sits with the two to learn more about their initiative, upcoming plans and their source for initiating a change in the Japanese society.

Tokyo Weekender: A week after news about the murder of George Floyd and the spread of the Black Lives Matter Movement hit Japan you organized an online discussion panel called “Break the Silence, Break the Violence” featuring some of the most prominent faces in the American hip hop and entertainment industry. What prompted you to organize this event?

Terry Wright: Anger. I’m a dancer and my crew has taught pretty much the entire first and second hip hop and house dance generation of Japan. We sort of built the entire ecosystem here. But there was a lot of silence from that entire scene and that made me angry because I couldn’t understand how it was possible to stay quiet at this time. So that was the reason that I made the initial post. It caught fire and I just didn’t want to let it hang, so I decided to use my platform to teach instead of just being angry.

What message did you want to convey to the Japanese public at the time?

Terry: The first thing is that I want people to know who we are. People often see our culture as a “product” — which is a terrible thing because a product is easy to throw away once you’re tired of it — but to us, this is culture. And culture is built on people. So I want to teach those people who are taking part in my cultural arts who we are, what we do and why we do what we do.

People tend to think that our culture started with hip hop but that’s a very big misunderstanding. American music equals black music. American dance equals black dance. The entire world’s entertainment is built around our culture, our sounds and rhythms — and much of this is built on trauma. And yet most people have no idea and put it out of context.

https://www.facebook.com/brooklynterry/photos/a.817691368326116/3069653229796574/

Hundreds of viewers joined the event — including many Japanese people. How do you think it was received in Japan?

Terry: I think there was a bit of confusion because many people don’t understand the ground floor of who we are and what we do. However, I believe this is positive because when you get confused, you want to dig deeper, which is already a good thing. It was positive for the most part and I think it sprouted curiosity.

View this post on Instagram

Many of us are fortunate to live without having to think about race on a daily basis. But this isn’t the case for black people, is that correct?

Terry: As black people, race is something we have to think about every day. I get stopped by police for nothing. Eight out of ten times when I get back to Japan from work overseas, my bags get checked. There is a problem with race in Japan, especially when it comes to black people because the entire identity of black people around the world is being controlled by white people and by the media. So the way you see me, the way she sees me [points at Naomi sitting to his right] initially is the image that they gave you of me. We can’t even be who we are sometimes.

“The entire identity of black people around the world is being controlled by white people and by the media.”

I ask my Asian friends and my Japanese wife about how often they have to think of being white and Asian. In Japan, you do have to think about it sometimes. But if you leave Japan, maybe not so much. But being a black person, it’s constant. I have to constantly think about who I am and the color of my skin. It’s a constant weight that we have to carry just because of something that is not a negative thing: I simply have more melanin than you in my skin and that’s it. People here — because their image of me is controlled by Western European and American white supremacy — they automatically see it as a negative connotation.

Before you came to Japan, did you think it’s going to be different here?

Terry: I’ve been coming to Japan on and off for almost 25 years now. When you come here as a tourist you don’t see those things. But I moved here permanently 14 years ago and many things started to get a little more obvious. At the first apartment I moved into — it was small but brand new — I had a conversation with the building owner who was racist and she didn’t even know it. She would say, “Aren’t you so lucky to live in a beautiful place like this now?” And I said, “What do you mean, I’m from New York City. I’m from Brooklyn, New York.”

Many foreigners ask me for advice about moving in Japan and I always tell them that rule number one is that you’re not Japanese — no matter how much you speak the language or know the culture, you’re not Japanese. Rule number two is the tiers — Japanese people are at the top, white people are next, down at the bottom are black people along with non-white Asian people.

Many foreigners in Japan feel pressured to fit in specific categories: If you don’t fit the “sellable” categories, chances are you won’t make it in Japan. If we want to change the narrative, we have to start addressing this issue. But what can we do to start changing the narrative?

Terry: Don’t be silent. As a top-ranking dancer, I have a position in the dance world. Street dance in Japan is huge. I would go to events and I would feel like I just didn’t belong there. That is my cultural dance — literally, my move, and still I felt like I didn’t fit in. And I got tired of this so I decided to create my own thing and instead of going to people, I had people coming to me. I control my narrative. And I feel that, as foreigners, we often forget that we can still change that, we can still control our narrative. I created a platform called Speakeasy Tokyo and that became one of the biggest parties in Tokyo. It’s [successful] because I didn’t allow anyone else to control it.

Naomi, why did you get involved in the founding of Japan for Black Lives?

Naomi Kawahara: I was angry when George Floyd died. But while I was angry, my Japanese friends were still posting selfies on social media and it struck me that Japanese people don’t know what’s going on — or maybe they’re filtering out the information when it’s in English. I couldn’t just sit and watch this happening in Japan.

When Terry posted something in Japanese about the movement, many Japanese felt something. But at the same time many of them started reacting by just posting black squares or hashtags on social media without really understanding the background. I felt that as a Japanese, it’s my responsibility to raise awareness about racism in our language. So I asked Terry to launch a Japanese website through which we can educate Japanese people about the issues. The site is japan4blacklives.jp. We focus on producing articles that explain the nature of racism through various angles. On our related social media sites, we also add Japanese subtitles to videos on various topics that are circulating social media.

How has the initiative been received so far?

Naomi: Many Japanese people are messaging me, saying that they really didn’t know but now they understand. It’s a good reaction.

Terry: I think that this coming from a non-mainstream media in Japan is a key factor. What she did is put context. A lot of people will see videos that they don’t necessarily understand and just get the impression that “black people are angry.”

これは強烈。オハイオ州ベセルの白人至上主義者の男たちに囲まれた、一人のBLMプロテスターの白人男性。突然、強烈に後頭部を殴られるも一部始終を目の前の二人の警察は見ているだけ。正義はなく、警察の助けもない。 https://t.co/r0yhIKIxTb

— Japan For Black Lives / 黒人差別への理解を深めよう (@jp4blacklives) June 17, 2020

One of the viral SNS videos that Naomi and her team worked on translating for Japanese readers. The Japanese caption explains and analyses what is happening in the video for those who couldn’t understand from the original. This is one of the many posts that Japan for Black Lives is working on to translate in a bid to spread awareness among Japanese viewers.

Naomi: Did you watch that NHK video? For that one, I added subtitles in Japanese explaining what’s bad about it. Then I started receiving messages from people saying that they’ve only just begun learning about racism in America but even they think that (that video) is not okay.

You’ll hear many people say that the BLM has nothing to do with Japan. What do you think of that?

Terry: I’m going to relate this to Japan’s dog culture. Say you don’t own a dog but you walk down the street and you see someone kick the shit out of the dog. Then a Japanese person would say “hey, why would you kick the dog?” Because that’s just the right thing to say. When people say “why should we care,” it literally feels like we’re less than a dog for them. Why should they care? Because we’re human.

Naomi: Many Japanese react to things only if it “sparks joy.” Since this doesn’t spark joy, they don’t react. Since I started working on the website, I’ve received quite a few anonymous messages from Japanese people telling me that I should instead think about problems that are happening in Japan (instead of talking about the BLM movement). But that’s precisely the same logic as “all lives matter.” Another person sent me a message asking why I started doing this now. Sometimes they’d think that if someone is so passionate about something, they’re just opportunists.

“We can’t even be who we are sometimes.”

Terry: I got asked by someone if I would think of them as hypocrites if suddenly they started enjoying hip hop culture because of everything that’s going on. And I said no, because it’s not about what time you’re getting on the train, it’s about getting on the train. Your station is your station. You just get on. But if it passes and you miss it, that’s when the problem begins.

Based on your experience, how different is racism in Japan and in the US?

Terry: Racism in the US is violent. In Japan, you don’t have to think about dying and you can actually talk shit to the cops. But in Japan, racism is expressed through microaggressions and those go deep. Those microaggressions can slowly deteriorate who you are. I’ve heard so many times people saying that there’s no racism in Japan. But if you’re staying on that side of the road, how do you know what’s happening on this side of the road? [The prevalent mentality is that ] If it doesn’t affect you, it doesn’t exist.

Naomi: I used to feel that way myself because I’ve never had a negative attitude toward black people. But then I realize that we haven’t really tried knowing [them]. I had a black friend who once asked me to put his open drink in my bag when we were entering a store because he was afraid that the staff would think he stole it. That shocked me because it had never even occurred to me that someone would think that way.

“I felt that as a Japanese, it’s my responsibility to raise awareness about racism in our language.”

Terry: That’s our reality. I can get accused of stealing if I only walk into a store. When you try to explain that reality to someone who hasn’t lived through it, they may think you’re crazy. All I’d say is, please listen. If people start telling you that you’re thinking too much, it makes you feel even more crazy.

Do you discuss racism with your Japan-born children, Terry?

My kids [aged 11 and 12] have already experienced racism. We were at a pool at a beach house in the US when some members of the community came to ask if we were allowed to be there. My son asked me why they were asking such things. I have to explain to him everything that’s going on. The hardest questions my kids ask are “Why are these people racist” and “Why do white people hate black people?”

My son said he cried when he heard about George Floyd’s death. This makes me upset. It’s tough to bring kids up in that kind of environment when I know — I know — that he’s next. He and his sister are going to experience this somewhere. It’s heartbreaking. Back in the US, I have to teach them to be careful when playing — when they’re just being kids — if the police approach them, teach them how they should act. I have to explain the same to their mom and teach her to grab them and I explain what to do. It’s tough because I know that parents who don’t look like me don’t have to explain such things to their children.

“The hardest questions my kids ask are ‘Why are these people racist’ and ‘Why do white people hate black people?'”

[In Japan], because we own a dance school and our kids’ friends go there, our kids are the cool kids at school. The black kids in our neighborhood all go to the same school. So I know that (them at) elementary and junior high school will be fine. But the reality is that high school is coming and they’ll have to leave their safe bubble soon. I’m beginning to prepare both of them for leaving the bubble. And I do that by building up their confidence. My daughter wanted to straighten her hair and I said no, everybody wants to have hair like you.

What’s the next step for Japan for Black Lives?

Terry: I would like to continue to educate. We’re now organizing our next panel discussion. I want to be able to teach at universities in Japan and help people to make a foundation [for discourses on racism] because there’s none here. Japan is changing. What it means to be Japanese is changing. So if we don’t lay the foundations of how people think of racism now, there’s going to be a lot of problems in the next 10, 15 years. So my goal is to help build the foundation on which the house can stand. Turn my anger into education.

Terry Wright and Naomi Kawahara (right), founders of Japan For Black Lives. | Photo by David Jaskiewicz, Tokyo Weekender

Naomi: I don’t want this to end as a trend. I want to keep adding more content to the site and continue spreading the word. We’ll also have another event. Last time, I felt that it was difficult for many Japanese to reach a level where they can talk with our African-American panelists. Some of the questions they addressed were very basic — such as why we shouldn’t use the N-word. We want to narrow the distance in communicating.

Terry: I have to say however, I think maybe for the first time in my life about this situation, for the absolute first time, I’m actually optimistic. I see so many white people also fighting to make a change. There was a video about a girl arguing with her parents about racism, telling them that they are wrong. This 14 or 15-year-old girl is saying to her parents that they are wrong. She is the next (person to initiate change). If there are thousands and thousands of that girl, then we’re okay. My mother, who is in her 70s, said that there hadn’t been so many protests even during the Civil Rights Movement. Protests are happening all over the United States and the world. First time ever in history. I think that the combination of the coronavirus and Donald Trump may have been that one punch on the face the whole world needed.

Japan For Black Lives’ second panel discussion, “Break the Silence, Break the Violence: Stereotypes and Cultural Appropriation” facilitated by Terry Wright and interpreted by Ryoko Ito (@iam.reeyo) will be held on June 25 from 22:30 Tokyo time. Find out more about the event here. Register to attend the event here.

If you’d like to support Terry and Naomi with translations for the website, reach out to them via Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.