As the pandemic related health and safety restrictions continue, live houses are left out and facing permanent closure. We speak to eight people in different positions across the music industry to find out how Covid-19 is threatening Japan’s music industry – and the ripple effect this is creating.

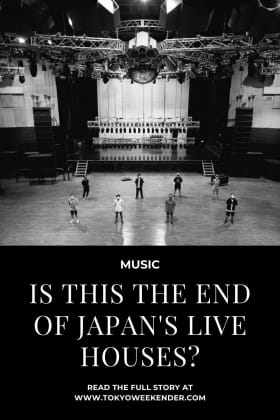

Our footsteps echo as we walk across the Studio Coast dance floor. This is one of Tokyo’s largest venues and instead of welcoming just over 2,400 people inside its walls, today it has only about 30. Studio Coast is not alone. Live houses across Japan have shuttered their doors — some for the last time. While crowdfunding projects like Live House, Live Force and Save The Live House have helped alleviate some of the worst financial hits, the efforts feel like a drop in the ocean. The Japanese government eased up on restrictions on July 10 so that indoor venues can host events with a maximum of 5,000 attendees, as long as it’s less than half of the venue’s max capacity. Unfortunately, the reality isn’t as simple as a numbers game — a venue found responsible for a Covid-19 cluster could face backlash and mar its reputation.

Nietzsche said that “life without music would be a mistake.” While that future seems a stretch, there is no doubt that the long-term closure of Japan’s many live houses will have a ripple effect on the music industry for the foreseeable future.

To find out more, Tokyo Weekender talked to eight people from across the music industry about how Covid-19 is affecting them and what can be done for the future.

How have you been affected by the Covid-19 pandemic and resulting state of emergency restrictions?

Kazuki Tsurumoto: Basically, we can’t do any business at all. We were close to bankruptcy. Before the pandemic, Studio Coast’s operation ratio was 77 percent. Our goal for this year was to operate at 80 percent capacity, so that’s about 290 events, but we probably won’t even break 100.

In June, we launched a crowdfunding campaign (at the time of writing, the campaign had raised over ¥20 million of a ¥10 million goal) but this whole time we’ve had no money coming in at all. Finally we’re seeing some bookings for shows without audiences and TV commercials, which is good, but about half of our income comes from drinks and coin locker fees. It doesn’t feel like there’s a light at the end of the tunnel. Venue staff don’t have anything to do so we’re delegating other tasks or sending them home. But even if things return to normal, they may not come back to work. People with experience will end up somewhere else, so we lose out on that know-how. It’s sad.

“We’ve lost 99 to 100 percent of our income.”

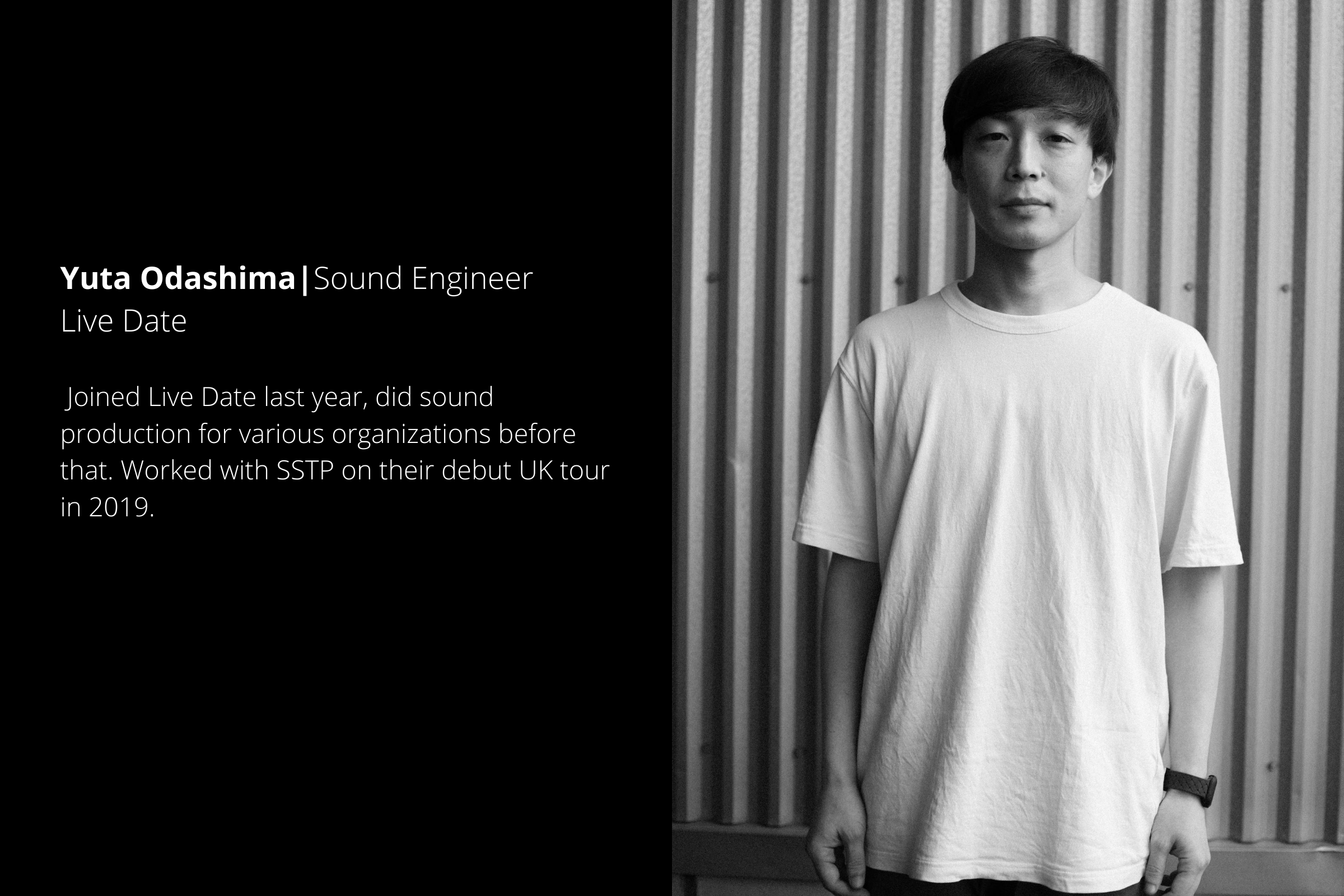

Yu Sasaki: We’ve lost 99 to 100 percent of our income. The last time we worked on a show was on March 28. From the beginning of April until the end of May we had zero money coming in. Our company only started a year ago so finances were already tight, but we still have to pay our employees.

Of course, there is help from the government, but we can’t wait. As for us engineers and technicians, all of our work comes from external sources – we can’t just make something out of nothing. So we’ve spent those two months thinking of ways to create work for ourselves in other ways. No one knows when this is going to end. Our estimate is that it’s going to take three to five years to recover. Of course, if we get work doing online broadcasting that’s great, but it wouldn’t cover more than 20 to 30 percent of what we do. It’s hard.

Takuro “Hiru” Hirukawa: Before the pandemic, we were working non-stop. The number of events we’ve lost is in the hundreds. And most things planned for this year have been pushed to next year. It feels like this year never happened.

Hayato Taguchi: We had to cancel a two-day event here at Studio Coast. That would have been an audience of about, what, 5,000 people? But if you consider all the canceled events, that’s tens of thousands of people missing out. On the band management side, it feels like we’ve lost all the hard work we’ve done until now. Bands have lost a way to communicate with their fans.

“It feels like this year never happened.”

I think a lot of artists have already started wondering if they’re needed. Even if you can see things in print, you can’t see the band’s faces. People will forget them. That’s what artists worry about the most, I think. People can still live without new music, which makes some artists lose courage. The most stressful thing is probably that everyone else seems to be going back to normal – just not us. We can’t do anything.

Yuta Odashima: So we wonder, are they really going to wait for us?

Seiki Matsuzawa: They’re waiting, aren’t they? I think they are. And while they’re waiting, we have to do something. I’ve been thinking a lot during this period, too, trying to come up with a plan. I think everyone who loves music will do something.

Sasaki: This is – from a personal perspective I should add – the thing, though. Everything is back to normal; it’s just that people are now wearing masks. People are going to bars and restaurants just like they used to. Except us.

Kei Miyadera: As for us, a ticket agency, when there are no events, we lose out too. We can only work when artists can perform. We have to come up with a system where everyone profits or everything will fall apart. We’ve talked about making an online broadcasting platform and we’re working on it. But because of the cost, it’s hard and it’s not really in our wheelhouse. But if we can sell tickets for a live broadcast as well, then everyone wins. Especially with the audience capacity restrictions, since fewer people will be able to go. It’s not perfect, but if we don’t do that, then…

What happens next? What will the music industry look like in the future?

Taishiro Fukudome: I think the keyword is broadcasting. There might be an advantage for everyone if there are both onsite live shows and online broadcasts. I started thinking: what if I were to do something for YouTube? For TV broadcasts? What’s the difference and why? I had the space and time to learn about something related to my expertise. They always say adversity brings opportunity, and I guess it’s true.

Matsuzawa: Until the pandemic, we had shows pretty much every day. That all changed, of course. But recently we’ve started letting bands with only a few fans perform. We’ve done some online broadcasting too. We’re installing a broadcasting system at Cyclone in mid-July. We want artists to have options. So they can perform with an audience, or just online with no people, or broadcast with people onsite as well. We have to come up with something that hasn’t been done before. I’m quoting Eikichi Yazawa here – he didn’t say this about Covid-19 but it still fits … “Music will never die.” In the end, people’s love for music won’t change. Even before this, the music industry has experienced so many changes. Instead of only focusing on the negatives, we have to concentrate on what we can do.

Miyadera: We’ve only been doing it for a month, but we’re broadcasting pretty much every day. I realized something: there are ways to enjoy a show at home that you may not be able to experience otherwise. It’s a different way to enjoy music and something for fans to appreciate. It’s also a way for people who can’t go to shows normally to enjoy them. It’s not all bad.

“A lot of artists have already started wondering if they’re needed.”

Taguchi: On the artist side and focusing on live performances, I think it’s quite clear that it’s an inflexible system – if one part is removed, everything else falls apart. If you can’t go on tour, or you have fewer shows, then you can’t monetize other things too. Without tours, it means we can’t pay crews and venues, but it also means fans aren’t mobilizing either. You’d be surprised at the number of people who will hop on a shinkansen to follow a band across the country. Fans also fill hotels. This is true for all major artists in Japan. These are factors that aren’t visible to the casual observer, but it’s something we are well aware of. Music does have a serious impact on the economy.

Tsurumoto: Yeah, I think the 7-Eleven near Studio Coast has seen a major loss in profit because of this. I would hand them our schedule every month and let them know approximate audience numbers so they could prepare.

Why do you think live houses are so important to the music industry?

Matsuzawa: I think it depends for the person, but live houses are a place to escape, like a kind of Neverland.

Taguchi: Small live houses serve as a place for bands to cut their teeth on the stage. If the number of small venues decreases it may not have an immediate effect, but it will affect future artists. For example, if – heaven forbid – Cyclone closed down, I think it would have a big ripple effect. I think it would also have an effect on the music produced. Because you’re consuming music differently – through earphones on a laptop for example – the sound will change accordingly. That can be good or bad, but personally I don’t think it’s good.

Matsuzawa: There are a lot of people who can create music without needing a live house. But live houses are often the first place a band has stood in front of a live audience. Even in a small venue, the excitement is still there. If they disappear, I think one of the major ways to enjoy music also disappears.

“If live houses disappear, one of the major ways to enjoy music also disappears.”

Miyadera: There’s something special about live houses and how they feel. It’s completely different from a festival. The first time I stood on a stage there were more people in our band than on the dance floor across from us. I think a lot of bands experience that. It toughens you.

Fukudome: I don’t think there would be an immediate effect – well there would be some – but in terms of extended influences? I think in five to 10 years the cool, competitive bands will disappear.

Any message for TW readers?

Taguchi: Everyone who has enjoyed music wants to share that experience with their kids. Rather than telling them, “When I was young, live shows were so much fun,” I want to go with them and share that experience. We often hear, “I can’t do anything, but I’m thinking of you” as if it’s an apology. But more than anything we want everyone to support us in any way they can, and to not forget us.

Fukudome: I think staying a fan and sharing your appreciation for the bands you like with others is the best way. That way the music industry will surely not die. Please come see us! We’re waiting for you! (Once things calm down.)

Photographs by Ryoko Ogawa