A 1950s study by a British psychologist created the belief in Japan — which some people still hold today — that a mother who works outside the home before her child turns three causes irreversible mental and emotional problems in that child. Now widely disproved here and around the world, it is known as the myth of a child’s first three years, or 三歳児神話 (sansaiji shinwa). Here, we look at how the theory came to be and why it took root in Japan.

Dr. John Bowlby’s Research

In 1951, British psychologist John Bowlby published a report called “Maternal care and mental health,” which he had prepared on behalf of the World Health Organization as part of a United Nations program for homeless children’s welfare. Bowlby was chosen for the job based on an earlier study, called Forty-four Juvenile Thieves, which compared the home lives of 88 children (44 with some history of theft and 44 “non-delinquents”) at the London Child Guidance Clinic where he worked. In that research, Bowlby found that 17 of the “thieves” had been separated from their primary caregivers for at least six months before the age of five, while only two non-delinquents had the same experience. He also discovered that 12 of the 14 children who were categorized as “affectionless” were found to have experienced complete and prolonged parental separation before the age of five.

Bowlby’s subsequent WHO study was based on existing empirical evidence gathered from across Europe and the USA. His main finding was that “the infant and young child should experience a warm, intimate and continuous relationship with his mother (or permanent mother substitute) in which both find satisfaction and enjoyment.” The lack of such a relationship, he said, can cause significant and irreversible consequences on the child’s mental health.

“In 2011, the average employment rate in OECD countries for mothers with children under the age of three was 51.4%, but in Japan, it was just 29.8%.”

Back in the ’50s and still today, Bowlby’s key findings are not particularly surprising. We can all agree that a happy, constant and reciprocal bond with at least one close adult is vital to nurture a healthy and well-adjusted child. The problem is what happened next.

The wording in Bowlby’s study clarifies that the child’s bond doesn’t have to be with its mother, but can be with a “permanent mother substitute,” like the nannies that were commonly employed by upper-class British families at the time. As the study’s findings spread around the world (it was published in 14 languages and sold over 400,000 copies in English alone), however, its finer points fell to the wayside. The idea spread that any separation from the natural mother would cause emotional deprivation in a child and that mothers, therefore, should not go out to work. This suited the political will in many countries at the time: governments wanted jobs for soldiers returning from the Second World War and removing women from the job market made that easier to achieve.

Keeping men in jobs and women at home

Japan also chose to keep men in jobs and wives at home. It started propagating the myth of the child’s first three years when it instituted blanket check-ups of three-year-olds in 1961, Japanese sociologist and author Noritoshi Furuichi wrote in a 2017 column on the Hanako Mama website.

Japanese media also fully embraced and promoted the idea. Newspapers ran features on it and, in line with the start of the check-ups, NHK created an infant education program aimed at mothers that became a best-selling book with more than 50 editions, Furuichi says. In 1979, a pediatrician called Shigemori Kyutoku, further released a book titled “Bogenbyo” (母原病), an abbreviation of 母親が原因の病気 (Illnesses that mothers cause.) It became a bestseller at the time. Backed by almost no scientific basis, Kyutoku’s theory blamed mothers’ poor child-rearing for ailments in children that included asthma, atopic dermatitis, school non-attendance and eating disorders.

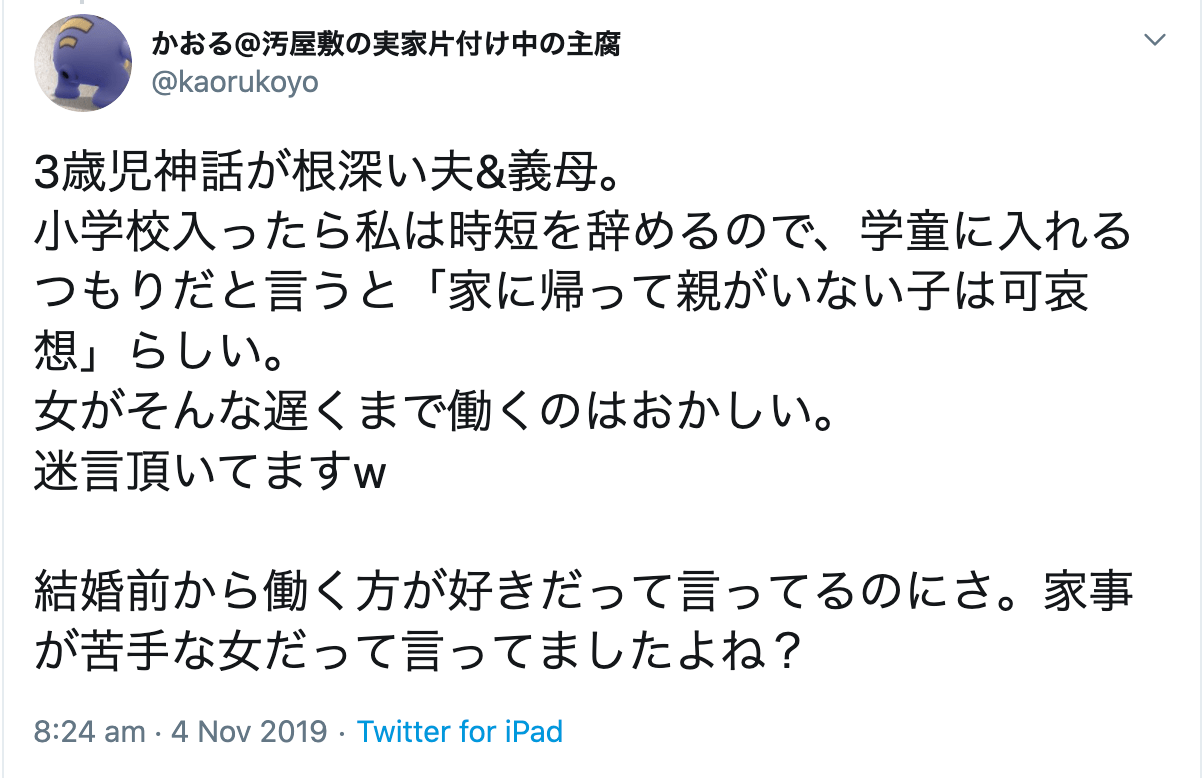

The young mothers of that era are now grandmothers and mothers-in-law, many of whom can’t help themselves from voicing concern over their grandchildren’s upbringing based on the social dogma of their youth.

Translation: My husband and mother-in-law strongly believe in the three-year-old myth. When I told them that I’d like to resume working full hours when our child enters elementary school and use after-school public child facilities, they said, “poor kid – his mom not being at home after returning from school.” Women shouldn’t work so late, they say. I thought I’d been telling them from way before we got married that I prefer working and I’m not good at housework.

As a result, although working mothers are now common in Japan, those who work through their child’s earliest years still battle criticism and stigma. Many don’t even try — in 2011, the average employment rate in OECD countries for mothers with children under the age of three was 51.4%, but in Japan, it was just 29.8%.

Moving on

Officially, at least, the Japanese government has moved on from the 1950s-1980s mindset. In 1998, a white paper from the ministry of health said that there is no logical basis to support the idea that mothers should stay home with their children during their first three years. The ministry’s commitment to that statement seemed questionable, though when it then explained to the parliament that it could also see no basis to deny the theory.

さすが首相が女性なだけあって、進んでるなぁ、ニュージーランド。

だって首相が在任中に産休とったりしてるんだもんね。すごいよ。

日本じゃ考えられん。

子ども3人産めとか、3歳まで親元で育てなきゃいけない三歳児神話とかまだ根強くある日本と大違いだわ。 pic.twitter.com/xfmizXwCxT— 菱山南帆子 (@nahokohishiyama) August 22, 2019

Translation: Way to go New Zealand! No wonder — it’s a country led by a woman after all. She even took maternity leave while serving as a PM. This can never happen in Japan. Such a drastic difference with Japan, a country where women are still told to have three kids and stay with them until they turn three.

In April 2013, as part of his growth strategy, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe called on companies to extend child-rearing leave from one year to three years, touting the idea with the phrase, “Cuddle your child all you want for three years, then return to work.”

Although it was designed to win over female voters, many criticized the idea of raising the responsibility for child-raising solely to women. Many foresaw a future in which companies, assuming young women would eventually take the three-year leave, would intentionally place them in jobs that could withstand such a long absence, effectively limiting job opportunities for them. Many women would have preferred to see changes that removed the social pressure for long working hours, preventing many fathers from taking an equal role in childcare.

Although progress is slow, in 2018, Abe’s Work Style Reform Law (a.k.a. hatarakikata kaikaku) was enacted to make Japanese workplaces more flexible. He has also attempted to provide more childcare and, in 2013, announced his “womenomics” plan to increase female participation in the workforce. It would appear that Japanese politics has, at last, ended its devotion to the myth of the child’s first three years.

Ongoing research

Research by Professor Masumi Sugawara of Ochanomizu University, which followed 269 child-and-parent pairs over 12 years, found no connection between problematic behavior and poor parent-child relationships when mothers worked before their children turned three. Studies conducted in the USA, even as recently as 2014, have shown similar results.

In a 2017 interview with NHK, another Japanese researcher and author of the book 母性愛神話の罠 (“The trap of the myth of maternal love”), Masami Ohinata, spoke about a survey of more than 6,000 mothers: “Even now the myth of the three-year-old is believed, and I wonder at how slow this change in human history and culture is.”

子どもを0歳など、小さい頃から #保育園 に預けることに、実は罪悪感を覚えていたり、もう復帰するの?と言われて傷ついたことがあるママさん、いませんか?😢#3歳児神話 どころか、0歳児でも家庭養育がベターだと裏付ける有力な研究はないそうです…!💡https://t.co/gA9yUyzhga#ワーママ #共働き

— m_relations@ ミレニアル世代の育児と仕事の両立を考える (@relations_m) July 24, 2020

Translation: Have you ever felt guilty for sending your child to a nursery? Have you felt hurt when asked, “You’re going back to work already?” There is no scientific proof that the three-year-old myth is true — in fact there’s no proof that home education is better even for children under the age of 1.

Ohinata warns, however, that there is part of the myth that should be upheld. “It is true,” she says, “that until the age of three is a very important period. We should not destroy (the idea) that during this time, a child’s ability to trust others is nurtured through being loved and experiencing confidence.”

What matters, she says — in line with modern research — is not whether a mother works outside the home or not, but the quality of childcare and whether she loves the child and is supported by her family and employer. As a society, we need to create conditions that support working parents and allow them the composure to be able to read a book to their children as they put them to bed, Ohinata says.

In a symposium article on the Japanese Society of Baby Science’s website, she warns of the ideological nature of child-raising theories, their potential for misuse, and the heavy responsibility that falls on the shoulders of those who form them. “Debating the truth of the myth of the three-year-old needs to be done with clear self-awareness of the high possibility that it could change the lives of parents and future parents-to-be.”