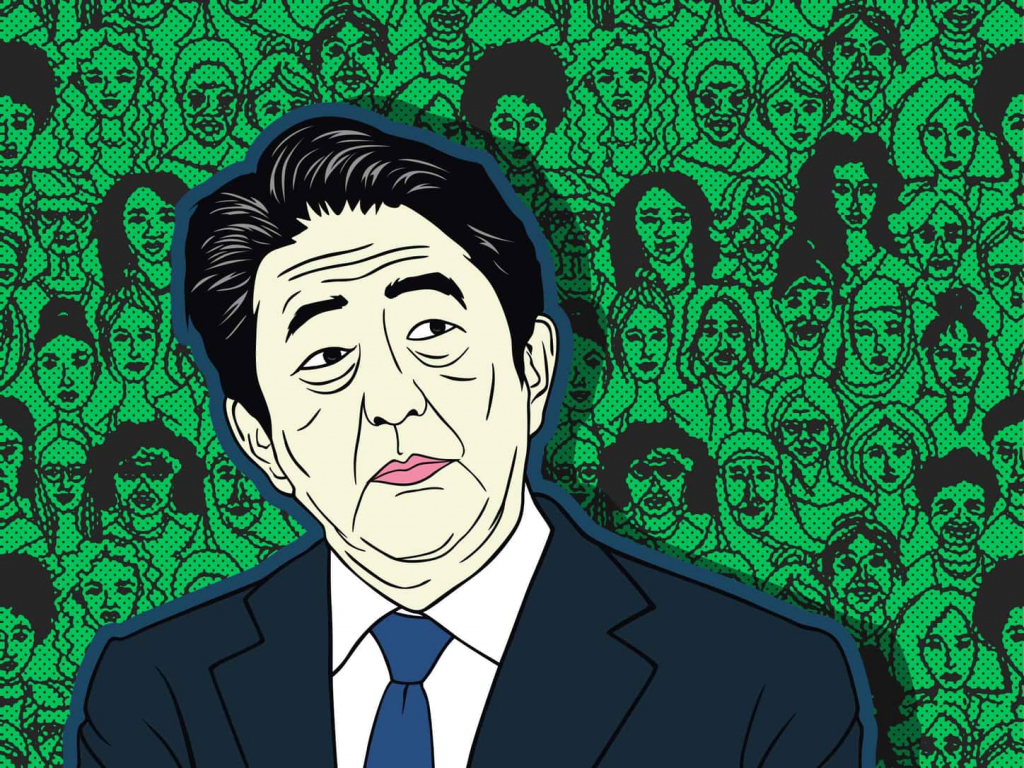

Not long after Shinzo Abe and his Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) came to power again in 2012, promises to women for a brighter and better future started making the news headlines. Women were going to be empowered, Abe said. Significant progress was going to be made in the quest for equality. Women’s position in the paternalistic nation was going to change.

All of this was going to happen thanks to “womenomics,” the Abe-guided savior of the double-X-chromosome half of the population and, more broadly, all of Japan thanks to the positive effects the policy was supposed to have on the Japanese economy in general. One of the main incentives for the initiation of the policy was, after all, the urge to find a solution for Japan’s low birth rate and aging population. The womenomics policy was included as part of the economic reform program generally referred to as “Abenomics” that was unveiled in 2013.

However, we’re now past the midway point of 2020, and it feels like the train to female empowerment and equality has barely left the station. Women still find themselves getting the short end of the stick, whether it’s being forced out of a job for having the audacity to request flexible hours for childcare or being denied opportunities for the possibility that one fine day they could have babies.

Women in Japan continue to find themselves stuck between a rock and a hard place, where a desire — and in some cases a desperate need — for solid paid work is hampered by societal and work expectations and a lack of decisive action and follow-through on the part of the government.

The long road to womenomics

Considering how long it took for womenomics to enter government policy, it’s perhaps not surprising that seven years on, not much progress seems to have been made. In 1999, the term was first used by Kathy Matsui, a leading proponent of gender-based reforms in Japan. In a Goldman Sachs report, Matsui and her colleagues argued that female consumption was vital to overcoming Japan’s slumping economy and that more women in the workforce could boost Japan’s real GDP growth by up to 15 percent. In other words, they argued that countries where women have equal status in government, work and social standing, tend to do better economically.

Womenomics Pioneer Tells Bosses to Nurture Female Talent https://t.co/GOGfc9fWci

— Kathy Matsui (@KathyMatsui) August 13, 2020

It’s almost a miracle it got picked up at all, though, when you stop to consider some of the comments that have spilled from the mouths of male politicians over those 14 years. Who can forget the then-Health Minister Hakuo Yanagisawa’s “baby-making machines” comment of 2007 or the “single and childless” heckling of a female politician in 2014?

A rough start followed by delays

It’s safe to say that womenomics didn’t get off to a great start. Anyone living in Japan in 2014 or consuming Japanese news at the time, will likely remember Abe kicking things off with a blog that urged women to “SHINE!” (in roman lettering) to put Japan on the road to a “sparkly” future.

Great idea, poor execution, since “shine,” when given Japanese pronunciation, sounds the same as the Japanese for “drop dead/F you.” Indeed — the lack of teeth that Abe’s proposals possessed and the lack of concrete steps the government has taken to pursue some of them do make the womenomics policy seem like one big F you.

“That’s not womenomics at work, that’s women getting burned while being told things are going in the right direction.”

That’s not to say that no progress has been made. Abe’s promise to reduce waitlists for daycare to zero by the end of fiscal 2017 (March 2018) hasn’t exactly gone to plan, but he and his government have at least managed to shorten the waitlist. April 2018 saw the number of children on waitlists drop below 20,000 for the first time since 2008. But the government still had to push back the promised deadline for getting rid of the waitlist to 2020, and some commentators argue that another of Abe’s policies — free kindergarten for all and daycare for some — will cause the waitlist to balloon again.

Delays like this seem to be a theme with Abe’s version of womenomics.

The goal to raise the ratio of women in leadership positions to 30 percent by 2020 — adopted by the government of Junichiro Koizumi in 2003 and much discussed by Abe — has also seen delays. The most recent adjustment to the goal is frustrating in its vagueness: it would be delayed by a “decade,” coming into realization as early as possible in the 2030s, the government announced in June. They promised a new plan, too, though no specifics whatsoever were even addressed.

#WOMENOMICS FAILURE#Japan PM Abe announced plans to create a “Japan in which women can shine” 7 years ago

Yet, #women still occupy less than 8% of management positions in Japanese corporations

Only 7.5% of companies surveyed have met the 30% thresholdhttps://t.co/55zxC8V3U3

— Kjeld Duits (@KjeldDuits) August 19, 2020

That the goal was not attained is no surprise given the companies’ lack of incentives to include women in their higher-up positions. In 2019, just shy of 15 percent of managerial positions in businesses and the civil service were held by women, while females were even scarcer in government, making up slightly less than 10 percent of lawmakers in the Lower House and about 14 percent in local assemblies.

Criticism and half-measures

Other proposals have also been made seemingly with little thought and have been met with harsh criticism. Among those is the proposal to extend childcare leave to three years. Many said three years would negatively impact a woman’s career, while some women worried it would increase already heavy pressure to stay home with young children. Some even argued that part of the reason for the proposal was to make the daycare waitlist issue appear less appalling — you know, children aren’t counted as being on a waitlist if their parents are technically on leave. As it stands, Japan allows up to a year of childcare leave.

“Womenomics is nothing more than a performance”

One issue that comes up time and time again in discussions among women considering a return to work after marriage is the tax deduction for dependent spouses, who are usually, but not always, women. A deduction sounds great, but means that women are severely limited in the hours that they work, as to receive the deduction, the non-breadwinner’s annual earnings must remain below a certain amount. It’s a powerful incentive to stick to flexible, non-regular work, and not terribly compatible with a policy that includes the goal of getting women into managerial positions.

There was talk of getting rid of the deduction altogether, but as of now, it still exists. Abe did increase the ceiling, but the bar was low to begin with and didn’t get raised much higher. Though the new policy is more nuanced, with the salary of the primary breadwinner taken into consideration and with partial deductions available beyond the basic ceiling, to receive the full deduction, annual income must remain at or below ¥1.5 million — do the math and you’ll know that that’s not typically the payment for a full-time position.

Misleading numbers

Despite all of the partial successes and failures, the percentage of women employed in paid work has increased to more than 70 percent, surpassing the percentages in Europe and the United States. As a result, there has been a certain amount of enthusiastic back-patting. But given that much of the rise has been in employment in non-regular work, it isn’t the success story that Abe and his government want you to believe it is.

According to a Japan Times article from June 2020, women with non-regular work make up more than half of the female labor force. As non-regular work is precarious and prone to going up in smoke at the first sign of economic difficulty, women end up anything but empowered. We’re seeing this right now as the Covid-19 pandemic ravages the economy. According to a June 18 article in the Nikkei Asian Review, in the two months leading up to publication, more than a million part-time female workers had lost their jobs — of the some 970,000 irregular jobs lost in April due to the pandemic, over 700,000 were held by women.

That’s not womenomics at work, that’s women getting burned while being told things are going in the right direction.

Beyond Japan’s borders

Regardless of whether the position of women in Japan feels better, worse or about the same today as it did seven years ago, internationally speaking, the situation isn’t looking good, with Japan’s position on the Global Gender Gap Index continuing to fall.

In 2020, it ranked 121 out of 153 countries. That’s down from 101 in 2012, the year Abe came to power. Looking at Japan’s regional ranking in East Asia and the Pacific category, the country comes in at 18 out of 20, being outperformed by every other country in the region except Vanuatu and Papua New Guinea.

Looking at sub-indexes, Japan ranked 144 out of 152 in Political Empowerment and 115 out of 153 in Economic Participation and Opportunity — not exactly rankings to brag about. The report also asserts that women in Japan spend more than four times on unpaid work, mostly domestic, than men do. All the daycare and managerial positions in the world won’t make a difference to womankind’s overall empowerment if society remains so incredibly unbalanced in the domestic sphere.

At the end of the day, it’s hard to believe that Abe’s brand of womenomics is about empowering women at all. If anything, it feels like empty words, hollow promises and half-measures designed to look good and improve the economy just enough to make it appear as though womenomics is working, women’s empowerment and well-being be damned.

Back in December 2014, the South China Morning Post quoted Yuki Kusano, then of the Japan Women’s and Human Rights Network, as saying that “Womenomics is nothing more than a performance,” and that the women who live here understood that. It’s now August 2020, and it doesn’t feel as though much has changed — or that it will at all.