Over the course of the lifetime of the Tokyo Weekender so far, Tokyo has transformed beyond feasible comprehension. From the guiding light of Japan’s post-war reconstruction to governing decades of prosperity, there are now few cities worldwide that have quite the same gravity of global cultural impact.

And, appropriately, music in the capital has been totally transformed since 1970 – TW’s first year of existence. Beginning with revolutions that blasted out of the confines of traditional pop genres like enka and kayōkyoku, the decades since have only spewed more musical upheavals and insurgencies.

Fifty years of music in Tokyo is, as with music in most places, fundamentally a story of extreme diversification. From pop charts to esoteric local scenes, the one consistency of Tokyo’s music has been its increasing variety. Indeed, one can exclude the musical innovations of the rest of Japan and still have more musical breadth than most countries (in no small part because, even in 1970, Tokyo had a population of 23 million).

Touring the past half-century and reporting back can be an overbearing task. It was a period of horizonless diversity and faceted legends, bulging arenas and alleyway venues, local heroes and global superstars, as well as of countless landmark cultural moments and fascinating musical stories.

Accordingly, there are immeasurably greater numbers of musicians that deserve inclusion in this piece than I can realistically contain. In their stead, I’ll keep the artists per decade to three, with a bit of context to sum-up each era best.

1970s

At the very beginning of the 1970s came one of the most notorious events in the history of Japanese pop music. The 1971 “Japanese-language Rock Controversy,” spurred a public discussion around the appropriability of the Japanese language for styles of music that originated overseas (specifically regarding Happy End’s folk rock work Kazemachi Roman). From that sprung many of the genres that ‘70s Tokyo is most renowned for – the likes of folk rock, psychedelia and, of course, city pop – as well as, feasibly, most styles of Japanese-language pop music to this day.

Best-selling album: Yōsui Inoue’s Kori no Sekai (1973). The “Emperor of Japanese Folk-Rock”, known for his sunglasses, eccentric lyrics and second-nature ability to sniff out pop trends, Inoue’s been a pop culture icon for half a century.

Haruomi Hosono

Haruomi Hosono is one of few Tokyo-based musicians whose importance spans large swathes of both the musical spectrum and each of the last five decades of Japanese pop music. In the ‘80s he was steering techno-kayo, innovating within Japanese progressive electronica and laying the groundwork for Shibuya-kei. In the ‘90s and 2000s he was working behind the scenes producing a huge variety of albums, from chart pop songs to film scores.

His groundwork in the ‘70s, however, not only produced some excellent music but helped cement Tokyo as a thriving, innovative global music hub. Beginning the decade with psychedelic rock act Apryl Fool, his next band Happy End were pivotal to the transformation of attitudes towards the use of Japanese lyrics in styles of pop music that originated outside of Japan.

Hosono went on to perform on almost every essential city pop record of the ‘70s, as well as play bass for other iconic Japanese albums like Osamu Kitajima’s psych-folk epic Benzaiten (1976), Akiko Yano’s Japanese Girl (1976) and Ryuichi Sakamoto’s Thousand Knives of Ryuichi Sakamoto (1978). Hosono’s solo works were bold, political and progressive, he was part of jazz fusion maestros Tin Pan Alley and, to cap it all off, he ended the decade by going global with Yellow Magic Orchestra – one of the most popular and influential Japanese music acts ever.

Taeko Ohnuki

Taeko Ohnuki may not have gotten around quite so much as Hosono in the ‘70s but she’s equally emblematic of that era. Those more fond of her techno-kayo works, which dated from 1980’s Romantique onwards, may have a different stance but, for me at least, it’s her contributions to city pop that land her as one of the most representative of artists of the decade.

https://youtu.be/fH-98i5J6ME

Her band Sugar Babe, with Tatsuro Yamashita, are one of the most identifiable early city pop artists. Taking the reins from Happy End, Sugar Babe diversified pop music on their own terms and paid the price for being ingenious before the masses – and critics – were ready. After years of being booed off stages on Tokyo’s circuit of live houses, Sugar Babe broke up before their singular album could garner proper recognition.

That album, Songs, has nevertheless been canonized in the decades since as a timeless and groovy collision of funk, jazz pop and soft rock. It’s an important Japanese pop record – as are many of Ohnuki’s solo works – and throughout the ‘70s she continued to produce albums of longstanding importance and popularity. Sunshower (1977) and Mignonne (1978), both collaborations with Ryuichi Sakamoto, are mainstays for city pop fans to this day.

Flower Travellin’ Band

While city pop artists may have dominated the latter half of the ‘70s (and, for that matter, much of the ‘80s too), they only really account for one, albeit huge, instance of the diversification of Tokyo’s music scene. Aside from the popularity of folk rock in the first half of the decade were more niche projects that sprang up around the city, from Isao Tomita’s otherworldly progressive electronica to Akiko Yano’s art pop and Masayuki Takayanagi’s freely-improvised jazz.

Japanese psychedelia, despite being largely absent of the hallucinogenic drugs that drove the scene’s creativity and aesthetics elsewhere, was popular and influential.

Flower Travellin’ Band, known partly as the naked motorcycle-riding men on the cover of their album Anywhere (1970), produced some of the heaviest, most original psychedelic rock in ‘70s Tokyo. Their sound, an onslaught of chants and drone-heavy riffing, was influenced by both blues rock and South Asian mysticism. To this day, albums like Satori (1971) and Made In Japan (1972) sound remarkably weighty; obvious precursors to heavy metal and great examples from just one avenue of Tokyo’s first wave of psychedelia.

1980s

The 1980s saw the height of Japan’s economic boom and laid the foundations for the birth of idol culture. The ‘80s also, however, witnessed the so-called band boom, the term given to the influx of new bands and the strengthening of infrastructure to support them.

The establishment of a web of venues and rehearsal spaces throughout the city enabled artists to diversify further within various scenes and niches. From techno-kayo to DIY punk, progressive rock to metal, there emerged significant capacity for popular music that was more creative and eccentric.

https://youtu.be/pRAurbxw_tM

Best-selling album: Akira Terao’s Reflections (1981). Otherwise an actor known for roles in a few Kurosawa films (notably Ran and Dreams) and as a detective in TV series Seibu Keisatsu, Terao had a somewhat short-lived music career. Reflections, a by-the-numbers city pop work, was his first major label record yet sold 1.8 million copies in less than a year and, impressively, made Japan one of very few countries worldwide in which Michael Jackson’s Thriller was not the decade’s bestselling record.

Tatsuro Yamashita

Whether Tatsuro Yamashita was principally a ‘70s or ‘80s artist is almost purely a subjective matter. In the former he was another innovator of city pop, one-half of Sugar Babe and influential in both his solo records.

https://youtu.be/AbM3aAE-OmE

In the ‘80s, Yamashita reached peak popularity. His first number-one album Ride on Time came in 1980, followed by further success with 1982’s For You. “Christmas Eve” (1983) is, to this day, still a seasonal staple, while the effervescent, Yamashita-written, Takeuchi hit “Plastic Love” (1984) remains one of city pop’s most well-known tunes.

https://youtu.be/f3sU6DMzG1I

Yamashita’s end to the ‘80s is, however, what makes his decade stand out most for me. His later attempts at artier, more developed and more contemporary styles of city pop, nevertheless tied to the identity of his previous work, were exceptional. Albums such as Pocket Music (1986) and Boku no Naka no Shounen (1988) showed his stubborn quality, proof that Yamashita’s genius wasn’t just happy with birthing an era-defining style of popular music but continued to nurture all the way through it.

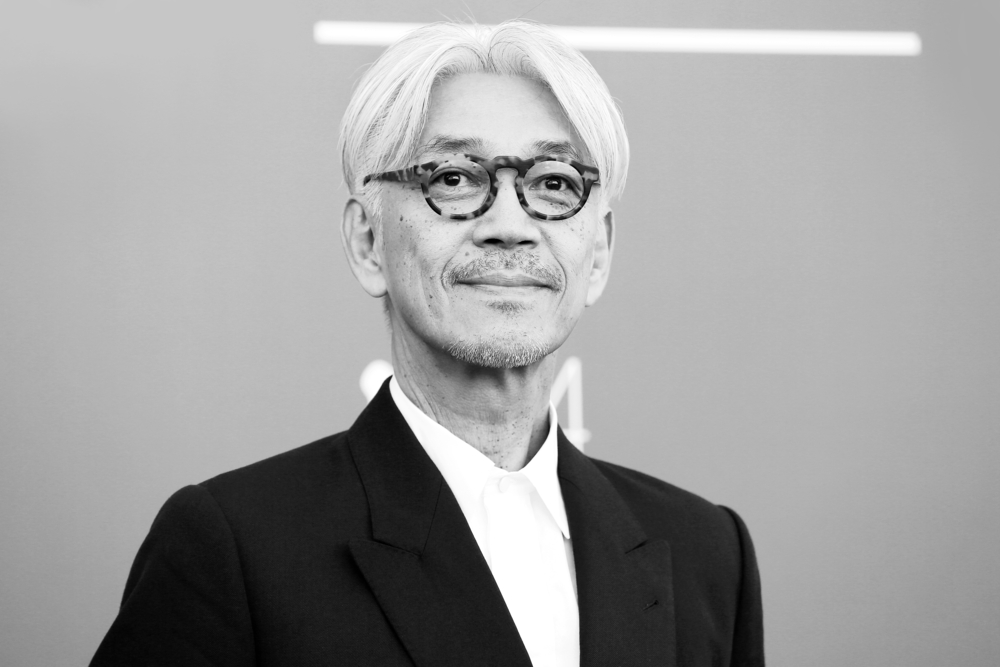

Ryuichi Sakamoto

Andrea Raffin / Shutterstock.com

Few careers capture the breadth of Tokyo’s music scene with such fluidity as that of Ryuichi Sakamoto. An immensely important figure in Japanese popular, experimental and orchestral music, Sakamoto’s beginnings as a classically-trained musician and ethnomusicology student primed him for a career full of staggeringly significant musical milestones.

Those milestones began in the ‘70s, as Sakamoto worked his way between essential city pop records, his own, more abstract solo pieces and pop megastardom with Yellow Magic Orchestra. His ‘80s saw him branch into industrial electronica, film soundtracks, modern classical music and much, much more, without relinquishing his hold on pop.

Though the importance of YMO in terms of its contributions to techno-kayo, synthpop, ambient house and wider electronica is well known, Sakamoto himself produced numerous game-changing works. His 1980 album B-2 Unit anticipated electro, a key moment in the history of dance music, while other works are credited with foreshadowing genres like IDM, broken beat and industrial techno and influencing hip hop beats of the likes of Afrika Bambaataa and Mantronix.

Sakamoto’s discography is vast, varied and far-reaching, venturing far beyond Japan in his collaborations with the likes of David Sylvian, Nam June Paik and Fennesz.

Jun Togawa

The band boom enabled unconventional musicians to thrive, finding an audience for more individualistic art. It was in this context -but also within her own alienated, dislocated world- that Jun Togawa thrived. One of the most fascinating characters in the Japanese new wave, Togawa kicked-off her ‘80s in advertisements for TOTO washlet bidets. That image, sexualized, infantilized and commercialized, stands at odds with the career that followed.

Renowned for an inimitable vocal delivery compiled of an array of howling, yelping, lullaby, crying and operatic belting, she sought to upend all preconceptions of the modern female pop star.

Togawa’s first notable band of the decade, Guernica (with Koji Ueno), mocked conservative nostalgia for pre-war Japan. Combining elements of German 1930s cabaret with synthesizers and drum machines.

With Yuji Miyake she formed Apogee & Perigee, a conceptual techno-kayo project about two robots; and with Yapoos, she explored futuristic styles of electro-industrial synthpop with absurdist lyrical themes that are, to this day, still futuristic.

Togawa’s solo albums, meanwhile, were even more radical. 1984’s Tamahime-Sama, a visionary work that juxtaposed a princess among a world overrun by insects, revolted against dainty feminine stereotypes through grotesque depictions of adolescent women. In the years since, Togawa has been the subject of academic scrutiny and inter-generational appreciation as a subversive, alienated and revolutionary icon of the Japanese new wave.

1990s

Following the ‘80s band boom came the popularisation of yet more diverse styles of popular music and the commercial peak of CD sales in Japan. In the 1990s, Tokyo was gripped by Shibuya-kei and visual kei but also saw the emergence of Japanese hip hop, the growth of dance music and the arrival of the term “J-pop” – heralding the advent of the pop agency industry that remains so dominant in the charts today.

Best-selling album: Hikaru Utada’s First Love (1999). Utada’s success capitalized on a decade of increasingly mechanised and corporatized music marketing: First Love wasn’t just the ‘90s’ best-selling album but the best-selling Japanese album of all time.

Keigo Oyamada

Due to its location-specific definition, Shibuya-kei may well have been one of the last half-century’s most Tokyo-centric styles of Japanese pop. Characterized by the shared ethos of musicians residing in Shibuya ward, it also happens to be one of the broadest, riddled with idiosyncratic artists.

https://youtu.be/j_F49QSHuDE

So varied was Shibuya-kei that it is, therefore, tough to pick only one artist to sum it all up. Even after one has considered renowned names like Pizzicato Five, and Fantastic Plastic Machine, there are a remarkable number, from Kahimi Karie to Hi-Posi, Towa Tei to Takako Minekawa.

Shibuya-kei’s most recognizable name, Keigo Oyamada, was a member of pivotal early genre pioneers Flipper’s Guitar and, under the alias of Cornelius, a groundbreaking artist in his own right. The former’s Doctor Head’s World Tower was jangly and rhythmic, a colorful mesh of Madchester beats, textured guitars and bright samples. The latter, notably on Fantasma, was more abrupt, peculiar and cut-and-paste but no less pretty.

Both Flipper’s Guitar and Fantasma show the position that so many ‘90s Japanese artists found themselves in following the burst of the economic bubble in the earlier part of the decade. Equipped with worldly record collections built at the height of ‘80s extravagance, Shibuya-kei artists found innovation in taking those records, shattering conventions of genre and fusing those sounds and influences into collages of plunderphonic genius.

X Japan

Like Shibuya-kei, visual kei wasn’t -and still isn’t- a genre in the usual sense. It’s noted more for its capacity for nonconformist self-expression, identifiable by its ostentatious dress, showy makeup, ornate hair styles and outrageous live performances. X Japan, one of whose early slogans termed the style (“Psychedelic Violence Crime of Visual Shock,” from 1989’s Blue Blood), were arguably the genre’s defining band.

X Japan formed in the late ‘80s but the peak of their relevance (and the apex of visual kei more generally) came in the ‘90s. Led by drummer Yoshiki Hayashi, they were trailblazers of a style that spawned a subculture with its own magazines and record labels, as well as its own ways of acting, dressing and dancing. Such was X Japan’s influence over visual kei, both actual and symbolic, that the suicide of guitarist Hide in 1998 is widely remarked as the beginning of visual kei’s popular demise.

X Japan are frequently cited as one of the greatest Japanese rock bands ever and, though that might be a bit contentious, it’s difficult to deny their influence and cultural impact. Musically, they were pioneering and produced some astounding works of symphonic metal (especially 1993’s Art of Life). Aesthetically, visual kei saturated the imagery and identity of Japanese popular music in the ‘90s.

Masami Akita

Rooted in some of the 20th century’s most influential and important artistic movements, noise music is a frequently misunderstood term. It’s ill-fitting, a vague bracket in which to pigeonhole anything that sounds too distorted or unusual rather than a specific genre that most artists actually identify with.

Peaking in the 1980s and ‘90s, Japan has proven a source of some of noise music’s most prominent names. Few have retained the genre’s individualism, intellectualism and politicism so ardently as Masami Akita, better known as Merzbow.

Named after a work by German Dada artist Kurt Schwitters, Akita’s Merzbow project has released over three hundred albums. To those who know little of the scene, many nevertheless know of noise music through features that often constitute Merzbow records: a space for raw artistic expression with extremes of volume and distortion, use of homemade instruments and imagery that is unfiltered in its depictions of the grotesque, erotic and destructive.

Though Akita was by no means a figurehead for Tokyo’s dispersed ‘90s experimental music scene, which included the likes of Keiji Haino, Otomo Yoshihide, Tatsuya Yoshida and Acid Mothers Temple, he is easily one of the better-known and more influential outside of Japan.

2000s

In ‘00s Tokyo, more so than in any other of the past five decades, consumers fueled high-quality pop music. Chart music found innovation when its equivalents in Europe and North America had grown somewhat stale.

Best-selling Album: Hikaru Utada’s Distance (2001) – Both Utada and Ayumi Hamasaki dominated the solo side of Japanese pop in the late ‘90s and early ‘00s. While Hamasaki came away the most successful Japanese solo artist of all time, Utada’s records were the landmark works, of which Distance was another. To-date, it was the fastest-selling (meaning it had the most first-week sales) Japanese album ever.

Hikaru Utada

Before she was even 20 years old, Hikaru Utada was already a pop institution. She’d established astonishing popularity for her characteristic, bilingual recipe of contemporary R&B and dance-pop. First Love and Distance, fuelled by hits like “Automatic”, “First Love” and “Addicted To You”, had sold well over 15 million records and were both the best-selling albums of their respective decades.

First with Deep River (2002) then again with Ultra Blue (2006), Utada produced works that were more than just fashionable, glitzy pieces of mass-consumed pop. Deep River included tracks like “Sakura Drops” and “Hikari”, more textured tunes with greater instrumental depth, as well as more emotional numbers like “Final Distance” – a song dedicated to a young fan murdered in the 2001 Osaka school massacre.

Ultra Blue was similarly distinguishing. Though virtually every track was primed as a potential hit, its combination of synthpop, ‘90s dance music and Utada’s dominant vocals produced another intense, atmospheric work. The legacy of Ultra Blue was reinforced by Utada’s decade-long hiatus from Japanese albums following its release but, even so, it’s a paradise of big-beat, hard-hitting J-pop.

Throughout Utada’s career, her success has been achieved on her own terms. Though she may never have been boundary-pushing in a radical sense, Utada has achieved dominance mostly with her own songwriting. Her career has largely been managed by her father: she’s an icon but she’s never been reduced to the same kind of forgettable mass pop act manufactured in Tokyo’s music agency boardrooms.

Sheena Ringo

Sheena Ringo, somewhat like Utada, also used early popularity to amass a platform for more ambitious later projects. Aside from the “pop” tag, however (and some collaborations over the years), there has never been much common ground between Ringo and Utada. Especially in the 2000s, Ringo was far more overtly experimental. The best of her music from that decade often feels like one has been caught in an onslaught of different genres and musical movements, a precisely-crafted, dense and fluid bombardment of unconventionality.

On more than a few occasions Ringo’s music actually topped the Oricon charts, a fact that, while understandable for her debut (1999’s Muzai Moratorium) grows more perplexing when one reaches records like Shōso Strip (2000) and, particularly, Kalk Samen Kuri no Hana.

Shōso Strip infiltrated ‘00s Tokyo as an introduction to Ringo’s eccentric and experimentally-tinged “Shinjuku-kei”. Kalk Samen Kuri no Hana perfected her ambition. A tight, dark, witty amalgam that juxtaposed pop and jazz rhythms against left-field innovation and Ringo’s atypical singing, Kalk Samen Kuri no Hana was deliberately poised to put-off fans and subvert her own popularity.

Instead, it was a masterwork that drove Ringo’s importance both within and outside of Japan. Ringo was just one of an increasing number of innovative Tokyo-based artists in the ‘00s that found widespread international recognition. Popularity that was previously limited to retrospection (such as Fishmans and much of city pop), niche experimental genres (like noise rock and free improvisation) or the standalone case of YMO, stretched to include Ringo – as well as others like Utada, Boris and Melt-Banana.

Perfume

Perfume round-out this triptych of ‘00s Tokyo pop. Originally from Hiroshima, A-Chan, Kashiyuka and Nocchi came to Tokyo in the earlier part of the decade. There they met Yasutaka Nakata, a post-Shibuya-kei electro-house producer whose hypermodern, ridiculously creative electropop productions would transform them into an era-defining Japanese pop act.

Perfume’s two defining ‘00s records, Game (2008) and Triangle (2009) are polished within an inch of their lives: comprised effectively of three robotic vocalists over speedy, popified, bastardised dance music.

Only all of that is precisely why Perfume’s sound was so innovative. While some popstars hark back to bygone eras or look to international pop styles for inspiration, Perfume had its sights firmly to the future. Once one realizes that everything they did was actually the product of a human mind, its genius is undeniable.

2010s

While it’s difficult to find perspective on such a recent time, the 2010s seem to have been a strange musical decade. The advent of streaming was largely ignored by most Japanese labels while idol groups like Arashi and AKB48 had an unshakeable hold on the charts.

On the plus side, the process by which Japanese music was projected to the world radically increased in breadth and reach in the ‘10s. Better global connectivity created a new generation of internet-famous Tokyoite artists, many of which found greater fame online than in Japan.

Best-selling Album: Arashi’s Boku no Miteiru Fūkei (2010). Though streaming services and YouTube make it increasingly difficult to gauge the best-selling studio album of the ‘10s, Arashi’s early-decade work Boku no Miteiru Fūkei seems to have very few competitors.

Kyary Pamyu Pamyu

When considering musical icons of ‘10s Tokyo, Kyary Pamyu Pamyu blares loudest simply because, as a rule, very little about KPP doesn’t blare. In an era where most pop stars are glammed-up in post-visual kei homogeny, her image -the syrupy, dazzling “Harajuku-kei”- radiates as utterly unique.

KPP (birth name Kiriko Takemura) began the decade as a fashion blogger and model. She then met Perfume producer Yasutaka Nakata, who persuaded her to pursue a music career. Nakata would write the music and KPP would provide the fashion, persona and performances.

KPP was looking for a new definition of “Japaneseness” not identified by traditional instruments like shamisen or wadaiko but more contemporary movements like chiptune and kawaii. Her image was saccharine, garish and grotesque, a J-pop fantasy that verged on parody. She was absurd, comedic and self-aware; so unlike anyone else, anywhere, that she became a fashion icon all over the world.

Sparkly, glossy and sickly sweet, Pamyu Pamyu Revolution (2012) and Nanda Collection (2013), their two most reputable records, were so consistently mind-broadening that they couldn’t help but go viral.

Seiko Oomori

Though many reactions to the ‘10s idol hegemony were little more than marketing ploys, counterculture cultivated by music agencies, among them were some worthy alternatives. Amid the more impressive likes of Sora Tob Sakana, Tokyo Girls’ Style and Dempagumi.inc, but also stylistically unlike any of them, came Seiko Oomori, who didn’t react against idol culture but patently adored it.

An “underground” idol, Oomori worked her way up from club sets on the local Koenji live circuit – in which she would roam the stage with an acoustic guitar, inspired by idol-pop’s energy and positivity- to major label funding. Nevertheless, Oomori’s music and image was adorned with the hallmarks of an artist rebelling against the norm.

In the earlier half of the decade, Oomori was best known for her provocative, raw, sexually-charged lyrics. From 2013 to 2018, she documented her prolific artistic instincts and, in a period of barely five years, she released around ten albums.

From her early, folky records and demos right through to her major label releases, Oomori’s most potent draw was her reputation for reinvention. Continually concerned with her own artistic evolution, Oomori could channel her individualism into her music like few others – making albums likes Senno (2014) and Kitixxxgaia (2017) volatile but fascinating works.

5lack

Among artists from previous decades that continued to perform throughout the ‘10s were throngs of Tokyo-based musicians that were important in their own ways: arena pop stars like Gen Hoshino and Sakanaction, critical darlings Ayano Kaneko and Shinsei Kamattechan, successful independent pop acts such as D.A.N. and Gesu no Kiwame Otome, as well as heavier icons The Novembers and Gezan.

One particularly notable feature of ‘10s Tokyo was the growth of hip hop. Hip hop’s decade began with a setback. The death of famed beatmaker Nujabes in 2010, the first Japanese hip hop musician to enjoy significant popularity and influence overseas, left the scene without its most influential figure.

Nevertheless, the following decade saw hip hop expand enormously in his stead, becoming both more mainstream and more experimental. Some, like Daoko and Suiyoubi no Campanella, found popular success in crossing the genre with electropop and electronic music, while the likes of U-zhaan, Moe and Ghosts and, at the very end of the decade, Dos Monos and Haru Nemuri pushed the boundaries of the genre far further than even the innovations of their American contemporaries.

Others, like STUTS, Punpee and Kid Fresino, offered a Japanese-language take on more classic styles of hip hop. 5lack (pronounced “Slack”) largely belongs in this final camp, though his importance spills over into an extraordinary number of different facets of Japanese hip hop. He straddles the popular and underground, experimental sides of the genre, a poetic, abstract lyricist and a consistent, versatile performer.

5lack’s 5 Sense (2013), Wake Up From Your Dream (2015) and KESHIKI (2018) are all classics and he’s had guest features on countless tunes across the Tokyo scene. He also, however, demonstrates the confidence of Japanese-language hip hop in the ‘10s. Whatever the track, 5lack possesses a smooth, jazzy, effortless cool.

Judging by the genre’s increasing ascendancy in 2020, Japanese hip hop looks set to dominate the near future of Tokyo’s music scene. As that hype builds, few deserve to be recognised as so crucial to the foundation of that scene as 5lack, a fulcrum of contemporary Tokyoite hip hop.

Ed Cunningham is editor of The Glow, a site that promotes Japanese music to English-speaking audiences