How do you capture the essence of a nation’s culture? And how do you then “summarize” that culture? Coinciding with this year’s Olympic and Paralympic Games, the Agency for Cultural Affairs and the Japan Arts Council have undertaken that task. The Japan Cultural Expo is an ongoing festival celebrating the arts — dramatic, culinary, literary, musical, humanitarian and more — from various regions of Japan. While this year incoming tourism will no longer bulk up Expo audiences, organizers hope that the festival will reawaken residents’ appreciation for the country’s beauty. Under the theme of “Humanity and Nature in Japan” — honoring the material and thematic expressions of nature worship particular to Japanese aesthetics — art shows are being held nationwide. Of course, with health precautions.

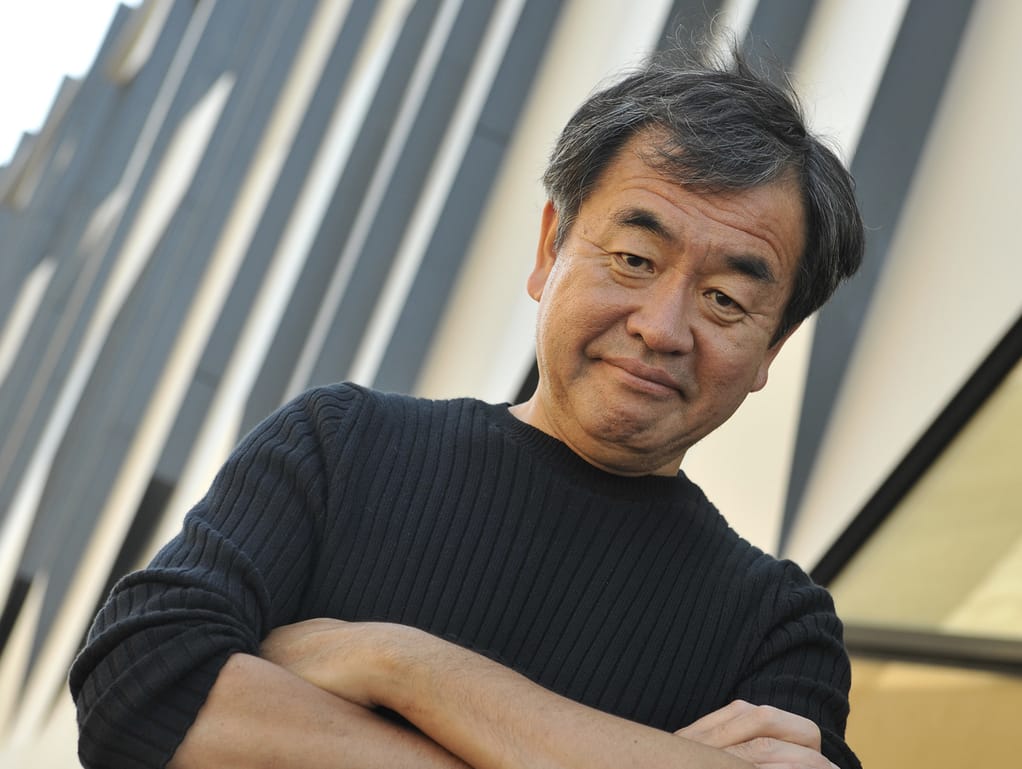

While these exhibits range from the prehistoric Jomon period to the Edo era, from Iwate to Izumo, there is a particular show that resounds with the current, indeterminate moment. As we cool down from a controversial, glorious, disturbing and history-making Olympics, many people might be thinking about what is next for Tokyo. It’s natural to have that feeling of emptiness and unease following a climactic moment. Architect Kengo Kuma has been thinking about that. And he has some ideas moving forward.

©Kioku Keizo Courtesy of The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, Installation view|Japan Cultural Expo Presented and Co-presented Projects

Kuma Kengo: Five Purr-fect Points for a New Public Space at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, not only rallies the works of a pioneering architect, it also tackles questions about how to display architectural works and the parameters of an architecture exhibition. Curator Kenjiro Hosaka has pointed out that there has been an increasing trend in Japan of hosting architecture exhibitions since 2017. But these rarely feature living architects like Kuma. And in Five Purr-fect Points, Hosaka refuses to have some curatorial agenda cloud Kuma’s own conceptions of his work and his hopes for the future of society. Kuma authors all of the explanatory texts in the exhibition.

We can see Hosaka playing with definitions of architectural “artwork.” As we are greeted by a wall of sectional plans, photos and wood samples for Kuma’s Japan National Stadium (the main venue of this year’s Games), we are prompted to ask whether these semblances and practical necessities are art. There are also video interviews with Kuma’s associates about post-disaster restoration and architecture. On top of that, there are moody, high-resolution videos highlighting the dips and mounts of select structures.

Changing the Tone in Exhibiting Architecture

The architect selected the projects to be displayed, arranging them into five categories – Hole, Particles, Softness, Oblique and Time. These categories define his ideal public building. Contrary to Le Corbusier’s self-professed specialized five points of architecture (roof garden, façade, etc.), Kuma’s points take into account great swaths of architectural history. They also consider the way regular people experience a structure.

©Kioku Keizo Courtesy of The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, Installation view|Japan Cultural Expo Presented and Co-presented Projects

Despite the abstract quality of these five points, Kuma insists that his design method is to reach such high-level concepts through the solving of practical problems. The pandemic, he says, has told us to be wary of the “box.” Not only the box-shaped buildings that are unfriendly to airflow and health measures, but also the social, political and economic box structures that breed many kinds of suffering. This suffering can be found in construction companies’ hegemony over cityscapes and, in turn, the homogenization of culture. It can be seen in the environmental abuse and neglect encouraged by insular, boxed spaces as well as the rigid, stressful schedules governing school and work. His five-point “Plan for Tokyo” is another major part of the exhibition. It ultimately revolves around human, animalistic perspectives that defy seclusion and immobility.

How Kuma Escaped His Box

Kuma says that towards the beginning of the pandemic, he escaped his own box and took walks in his neighborhood of Kagurazaka. He subsequently began to see public spaces of Tokyo in a completely new light. Maybe the revelation had to do with that longing for social interaction that became synonymous with the coronavirus. There’s newfound gratitude for communal architecture, for the environment, for sociability and “street life.” In this period, he drew special inspiration from the way cats navigate the city, namely the part-time strays. Their path is chaotic when not dictated by food.

As a counterpoint to the unruly roads created by cats, Kuma considers Kenzo Tange’s original “Plan for Tokyo” in 1960. At the time, Japan’s capital was experiencing immense industrial growth. It was just starting its transition from a wooden city to one of concrete. Tange’s aerial, geometrical, blocked plan for a city suspended above the bay is a product of these times. The plan was ambitious and expansionary. Kuma believes that the city needs something else now. He advocates for a return to organic, recycled and locally sourced materials. He calls for the integration of regional history and culture into design. For a sense of continuity with the environment, lest the structure becomes a box. And for renovating old buildings rather than building new bigger ones. These, and other measures, are aimed at preserving the city’s native heritage and promoting sustainable, environmentally conscious and prosocial architecture.

©Kioku Keizo Courtesy of The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, Installation view|Japan Cultural Expo Presented and Co-presented Projects

Two Approaches to Tokyo

To understand the differences between Kuma and Tange, which is to understand their respective Tokyos, we can look at their Olympic projects. Tange’s Yoyogi National Gymnasium, completed in 1964, has an eye-catching suspension roof, modernist aesthetic and unprecedented boldness. Kuma’s stadium couldn’t be more different. Boasting a forest of wooden supports with timber sourced from Japan’s 47 prefectures, it has a more delicate feel.

However, Kuma’s approach to reforming public space and his activities (which extend to aiding disaster relief and designing toys) are diverse. Five Purr-fect Points is the public’s first opportunity to regard his life’s work en masse. It’s a chance to peer into Shibuya Scramble and the Dallas Rolex Tower in the same day. Kuma’s works are practical and beautiful responses to problems that seem impossible to scale. This includes issues such as environmental and cultural degradation and the global health crisis. Rather than the anxiety that we have come to expect, we leave the show with some excitement for the future.

Kuma Kengo: Five Purr-fect Points for a New Public Space is on view at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, until September 26. For more information about the exhibition, see here.

A great variety of shows, as well as some digital content, from the Japan Cultural Expo. For more information about these events, see here.