What makes contemporary Japanese literature so cool? A stylish magazine, which prides itself on the quality of its translation and an irresistible urge towards literary play, offers more than a few answers.

The lives of a mythical sea horse and a trapped Japanese housewife fuse as one. A writer gets sent to a narrative hell of literary cliches as punishment for over-consuming stories. Aliens conquer the human race, appeased only by music.

The stories that can be found in Volume 2 of Monkey: New Writing from Japan are as intriguing as they are varied. This volume is loosely themed around travel, which makes a simultaneously obvious and intriguing truth float to the surface. True travel is about experiencing and digesting the world around us anew, which is why travel-related stories can produce such good writing. And in this case, it produces an excellent compendium of new and old Japanese writing.

“Contemporary literature was supposed to be very difficult, serious and not much fun,” says Motoyuki Shibata, a noted English-to-Japanese literary translator and co-founder of Monkey. “The newer writers have a different sense of language… their prose reads much more like music.”

Motoyuki Shibata. Photo by Eisuke Asaoka

What Monkey Magazine Brings to The Literary Scene

This is the second volume of the relaunched Monkey English Magazine. The first came out last October, after Shibata and the publisher of the Monkey Japanese Magazine received financing from the Yanai Foundation under Uniqlo. Editors Shibata, Ted Goossen and Meg Taylor are straightforward about their selection criteria: they select pieces they like. Their favorites just so happen to align with some of the trendiest names in Japanese literature in translation in recent years. They include authors such as Mieko Kawakami, Aoko Matsuda and Hiromi Kawakami as well as translators like Polly Barton, Jeffrey Angles and David Boyd.

Monkey, whether consciously or subconsciously, plays favorites to the trendiest names in town, even notching regular contributions from Haruki Murakami. So, this isn’t the place to discover unknown, path-forging writers. But these names are trendy for a reason: their stories remain fun to read while reaching towards penetrating ideas and themes.

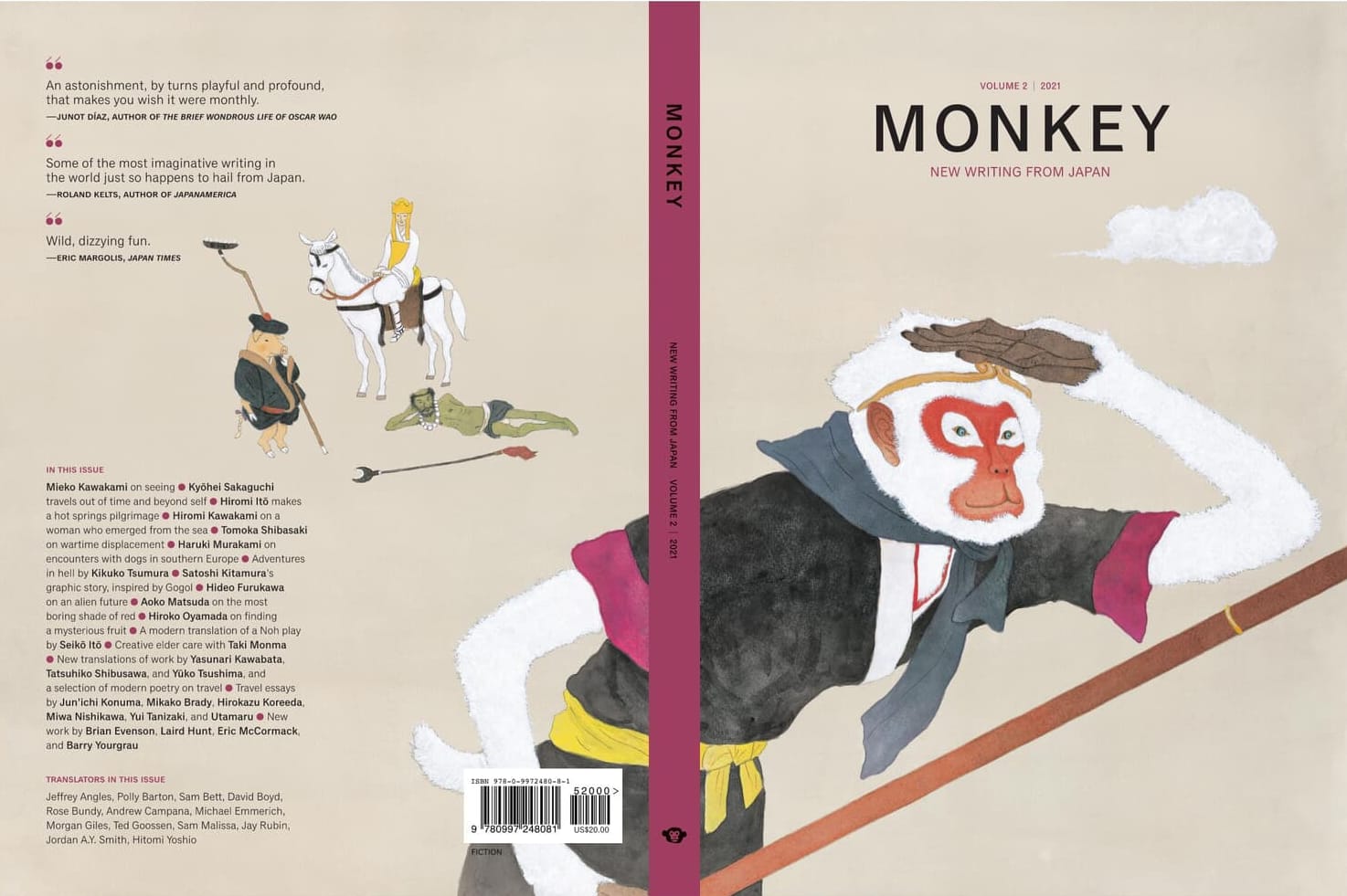

Monkey Magazine vol.2 cover art. Copyright Taiyo Matsumoto

Volume 2 Takes You on a Trip

The literary accomplishment of Volume 2, not as a collection of individual stories, but as a magazine in itself, hinges on one of my least favorite entries in the collection. “Every Reading, Every Sound, Every Sight” by Junichi Konuma and translated by Sam Bett is a meticulous, heady essay on travel that nonetheless gives the rest of the magazine meaning through its convolution of ideas.

This essay tracks the paths of various intellectuals and artists in the process of feeling out what exactly a journey is. Along the way, Konuma highlights the importance of travel and cultural exchange for art. But when I reached the end, Konuma’s declarations that “our plans are established over a substrate of nothingness” and “unless you see [travel] as a journey, it is simply movement,” felt like spotlights shining back at the rest of the volume, illuminating what I had read up until that point.

True travel is a journey. The same goes for good stories. Whether the characters of these stories go on long or short trips, the important point is that the authors write their travels as journeys, where observation, reflection and courage collide in an attempt to give birth to something new. The single best story in the bunch is Hiromi Ito’s “Ito Goes on a Journey, Making a Pilgrimage to Yuda Hot Springs” (translated by Jeffrey Angles), which does exactly that.

Cover page of “Ito Goes on a Journey” on page 98 of Monkey Magazine 2021. Art by Lauren Tamaki

Ito Goes on a Journey, Making a Pilgrimage to Yuda Hot Springs

While the narrator’s trip from Kyushu to Yamaguchi is an inconsequential five-hour drive, the journey that happens and the relationships that entangle along the way forge a powerful commentary on poetry, literature and history’s role in shaping life and death. Ito journeys across historical sites on her trip, not quite sure what to make of them, caught up in her own life, but digging towards kernels of truth. Reading this story alongside Konuma’s essay further brings out its unique power.

Ito the writer uses a unique literary device, borrowing the voice of the poet Chuya Nakahara (1907-1937) as a muse, infusing the work with the melody of poetry. Many other authors published in Monkey use similarly creative literary devices, playful forms of metaphorical magical realism that metamorphosizes into real experience and so on. “The Dugong” (by Tatsuhiko Shibusawa, translated by David Boyd) is a modern story riddled like an ancient fable. “Flying Squirrels” (by Yuko Tsushima, translated by Rose Bundy) takes a startling turn from peaceful summer memory into surreal meditation on children growing up. “The Lake” (by Kyohei Sakaguchi, translated by Sam Malissa) is a trippy dive into the nature of the universe within a single lake.

Art by Kyohei Sakaguchi

The Revival of Japanese Literature in Translation

Such creative qualities and strong literary devices are the same ones that have led to a ‘revival’ of Japanese literature in translation. From dead narrators (Tokyo Ueno Station by Yu Miri) to mysterious encounters (anything by Haruki Murakami) and sadist surrealism (Earthlings by Sayaka Murata), there is a high number of bestsellers and award nominations in recent years. Notably, most of these works have been written by women.

To shed light on why these stories are catching on in the foreign market, Shibata supposes that characters in an American and a Japanese novel are washing dishes. “In the American story, the characters think about reality,” Shibata says. “But in the Japanese story, characters wander into another dimension via the sink.”

Into the sink — into a journey. There’s undoubtedly something about the stories in Monkey that emphasize journeys, not just conversations and memories, moments and plots. Part of contemporary Japanese literature’s resonance may very well come from authors’ tendencies to configure as journeys.

However, the vivid detail and growth inherent to journeys only comes to life through the hard work of translation, which Monkey likewise puts a great deal of thought, effort and consideration into. “We are beginning to believe that this is our mission — to find good translators and work with them in meticulous ways,” says Shibata. “In that aspect, we are confident that we know what we’re doing.”

Art by Matt Currie

The Journey of Translation

Monkey further highlights another journey — the journey of translation. The magazine includes a unique “I can’t translate this” section at the end, where translators write a few paragraphs on a particular Japanese word or phrase that puzzles them. By extending beyond language, beyond borders (the magazine includes contemporary English-language writing from authors like Barry Yourgrau) and beyond historical period (with a Noh play and a Yasunari Kawabata translation in the mix), Monkey becomes a cross-temporal, cross-cultural, cross-lingual intermingling of stories and literature.

I can’t say that I personally enjoyed every entry. Brian Evenson’s “A Report on Travel” felt like a stiffly executed attempt at a quarantine story. But the overwhelming quality of the material highlights that, as many Japanese books and authors have found their way into translation recently, there’s plenty of more deserving material out there. Shibata will be the first to tell you that the list of material he wants to include far outweighs that which he is able to publish. In this sense, reading Monkey is a bit like a sampler for Japanese literature in translation. It gives you tasters of varied, sumptuous flavors that deserve whole novels worth of space to explore.