I love a good retrospective, one of those large-scale exhibitions that review the entire career of a single artist. Not only can you see how an accomplished creator developed over time, but you usually also come away with a sense of the individual as an artist, and perhaps more importantly, a fellow human being. “Kaburaki Kiyokata: A Retrospective,” at The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo until May 8, promises to do just that, taking us beyond the images of beautiful women for which Kaburaki is known, to learn what truly stirred his heart.

Kiyokata Kaburaki was born into a well-to-do and literary family in the Kanda neighborhood of Tokyo. His given name was Ken’ichi. Having shown an early aptitude for drawing, he was apprenticed at the age of 13 to an ukiyo-e master, who after a few years of training granted the boy his artist’s name of Kiyokata. Kaburaki’s career spanned a period of great change in Japan and its capital city, beginning during the Meiji Period in which he was born and continuing well into the post-war decades of rapid economic growth.

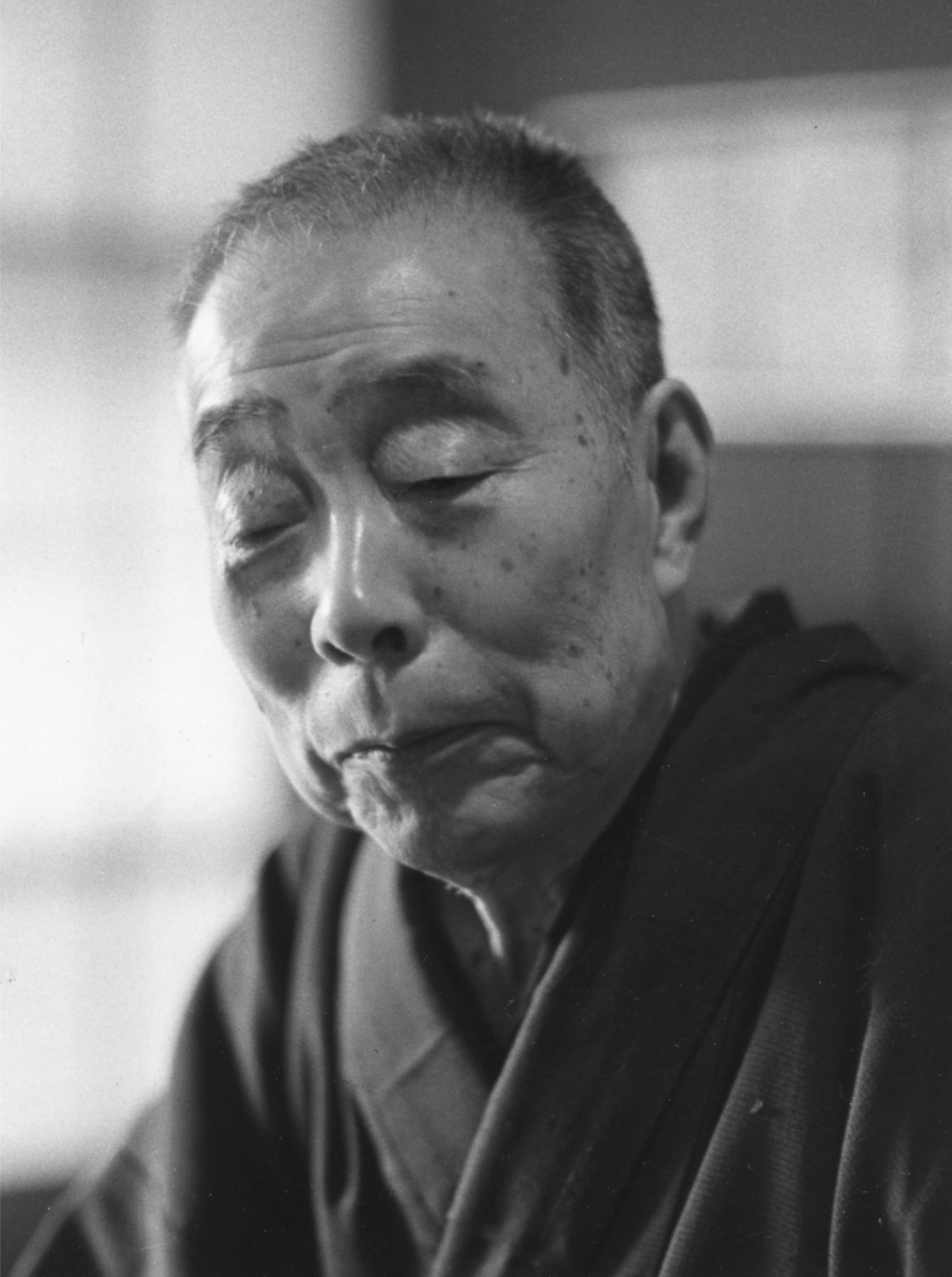

The artist in 1956. Image courtesy of the Kamakura City Kaburaki Kiyokata Memorial Art Museum.

Although Kaburaki started out as an illustrator, producing artwork for the newspapers his father owned, and later for popular novels, the exhibition skips over this part of his oeuvre to focus on his output as a painter. In sections organized by themes rather than chronologically, it presents a stellar lineup of more than 100 of Kaburaki’s paintings, 10 of which are being shown publicly for the first time.

One way the exhibition brings us closer to the artist is through a diary he kept that chronicles the years 1918 to 1925. In it, Kaburaki revealed his feelings about his own work, granting three stars to paintings with which he felt fully satisfied (kaishin no saku) and two to images that didn’t quite make the cut (yaya kaishin no saku). Those he judged merely so-so (maa maa) got just a single star. In the exhibition, 23 paintings bear captions sharing his self-evaluation. It will be fun to search them out and ponder what, in each work, Kaburaki considered worthy of praise.

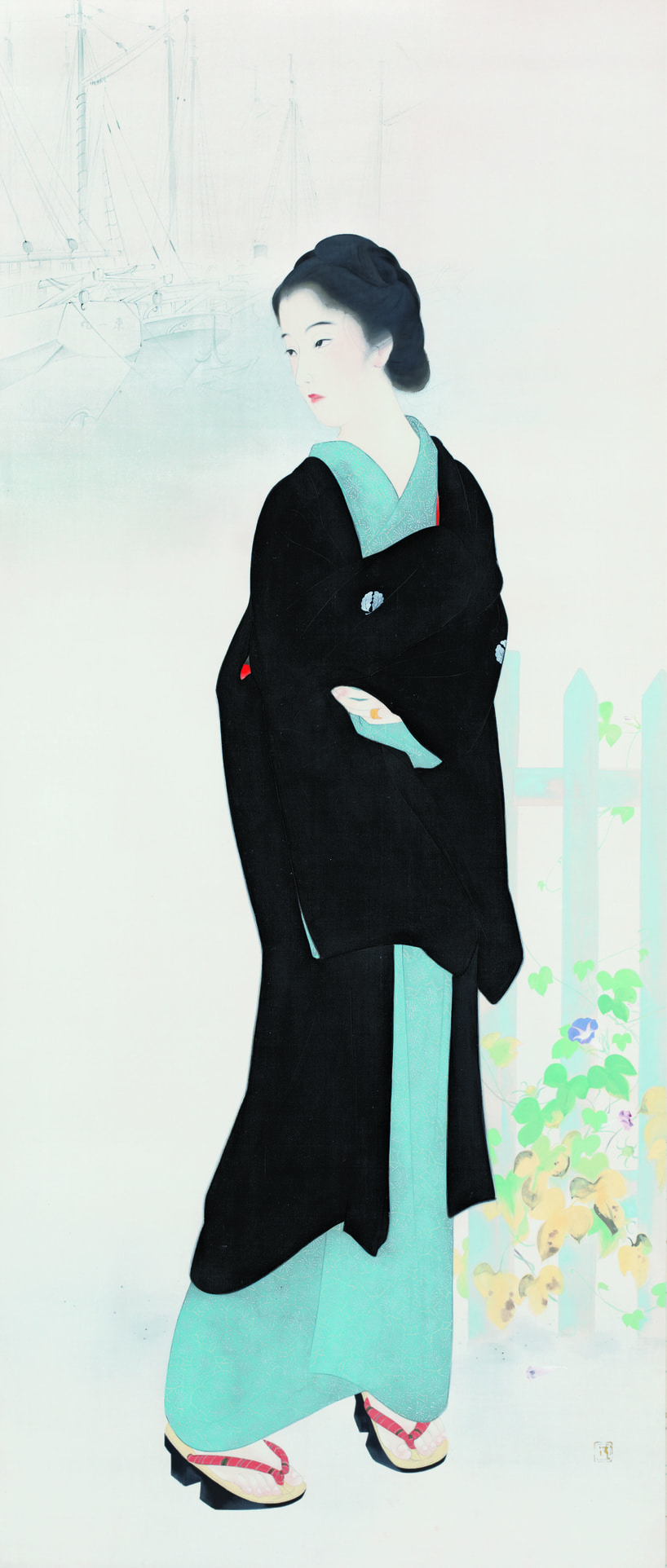

A highlight of the show is a trio of large-scale scrolls, each nearly two meters high, depicting standing figures of beautiful women. The three scrolls had gone missing for over 40 years until they turned up again in 2018 and were acquired by the museum. The most famous of the three – partly because it was reproduced on a postage stamp in 1971 – is “Tsukiji Akashi-cho Town,” a portrait of a slender beauty in kimono who has turned to look behind her. In 1927, the painting was awarded a prize in the prestigious Imperial Fine Arts Exhibition, establishing Kaburaki as a modern master of Bijinga, a popular and long-standing genre in Japanese painting of depictions of feminine beauty.

“Hina Doll Market,” 1901, Kitano Museum of Art. ©Nemoto Akio.

What a modern viewer might miss is that the woman’s hairstyle and clothing are the fashions of some three decades earlier, from around the turn of the century, while the faint, ghost-like details in the background refer to a place that no longer existed. Four years earlier, in 1923, much of Tokyo – including the Akashi-cho of the title – was destroyed in the Great Kanto Earthquake. Kaburaki was deeply affected by the loss of life and entire neighborhoods he had explored in his youth. The picket fence behind the woman, an unusual detail for a Japanese landscape, evokes the foreign settlement for which Akashi-cho had been known.

Such background details are so sparse they would be easy to overlook, but it is with these strokes of light wash that Kaburaki transformed Bijinga into something new, superimposing his recollections of lost cityscapes to create what might be described as portraits of places in time. His innovation triggered a wave of public nostalgia for the fashions and lifestyle of the Meiji Period.

For entries to the competitive salons, which catered to the elite and could make an artist’s reputation, Kaburaki followed the fashion of the day for large and commanding paintings. But his preference was for smaller formats on themes with more general appeal.

“Tsukiji Akashi-cho Town,” 1927, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. ©Nemoto Akio

“When I paint to outside demands, it is to create those images known as ‘Bijinga,’” Kaburaki wrote in a 1935 essay quoted in exhibition materials. “But where I place my own interest is in life. And within that, it is the lives of the lower rungs of society that interest me most.”

Kaburaki’s regard for the everyday activities of common people can be seen in his smaller works, a welcome focus of the present exhibition. Increasingly, he chose to work in what he called takujo geijutsu (table-top art), small-scale paintings that could be enjoyed in solitude, laid out on a desk or table. Smaller works were also easier to reproduce as illustrations in storybooks and novels, making them available to people who might not otherwise have access to art.

In loose and spontaneous brushwork, Kaburaki created nostalgic scenes of life in neighborhoods that had long since vanished from the rapidly changing cityscape. One example that drew my attention, in part because it shows an area near where I now live, depicts a young boy peddling fresh fish from baskets he carries on a pole over his shoulder. He has stopped to present his wares to a woman who has emerged from her simple home, and through the open doorway we can see even how her kitchen is equipped, with a wooden bucket of water readied for the washing up, and a grill hung neatly on the wall.

With such small works, Kaburaki expressed big ideals, striving to bring art to the people and encourage a more open society. And for us today, these charming images offer glimpses of beauty lost as well as insight into how people in our city lived their lives some 100 years before us.