My copy of The Housekeeper and The Professor lies on my coffee table. Just moments ago, I turned its last page and said goodbye to a beautiful cast of characters, each funny, tragic and human in their own way.

The journeys we go through as we explore books have never been more important than now, when physically escaping has become so limiting. “There’s more to getting a book in the bookstore beyond writing and printing,” says Erica Williams, founder of publishing agency Paper Crane.

How Books Get Translated and Published

It can be easy to forget that, like any other company, publishers are businesses first and foremost.

“First, we have editors, the people who work with writers to create the best version of their book possible. When an editor wants to acquire a book, they present it to their sales and marketing colleagues and try to convince everyone that the book should be published and, most importantly, that it will sell,” says Williams.

What a publisher might consider commercially viable could hinge on a variety of factors such as the current appetite for the book or whether similar themes are already in the pipeline. These attributes go beyond considering things that most readers would assume are of paramount importance, like plot, character and narrative. For avid readers, it’s a somewhat sobering thought to realize how much publishers must straddle the line between art and profit.

The popularity or virality of an author also comes into play.

“Publishers usually like it if the author already has a social media presence because that’s usually the target audience for the book – lots of pre-orders are the best way to get a book on bestseller lists and the best way to get the continued support from the publisher’s publicity and marketing departments,” reveals Williams. “Authors do get published without social media but it can be surprising to know how much authors are expected to promote their own books.”

Erica Williams

Japanese Authors and Novels Abroad

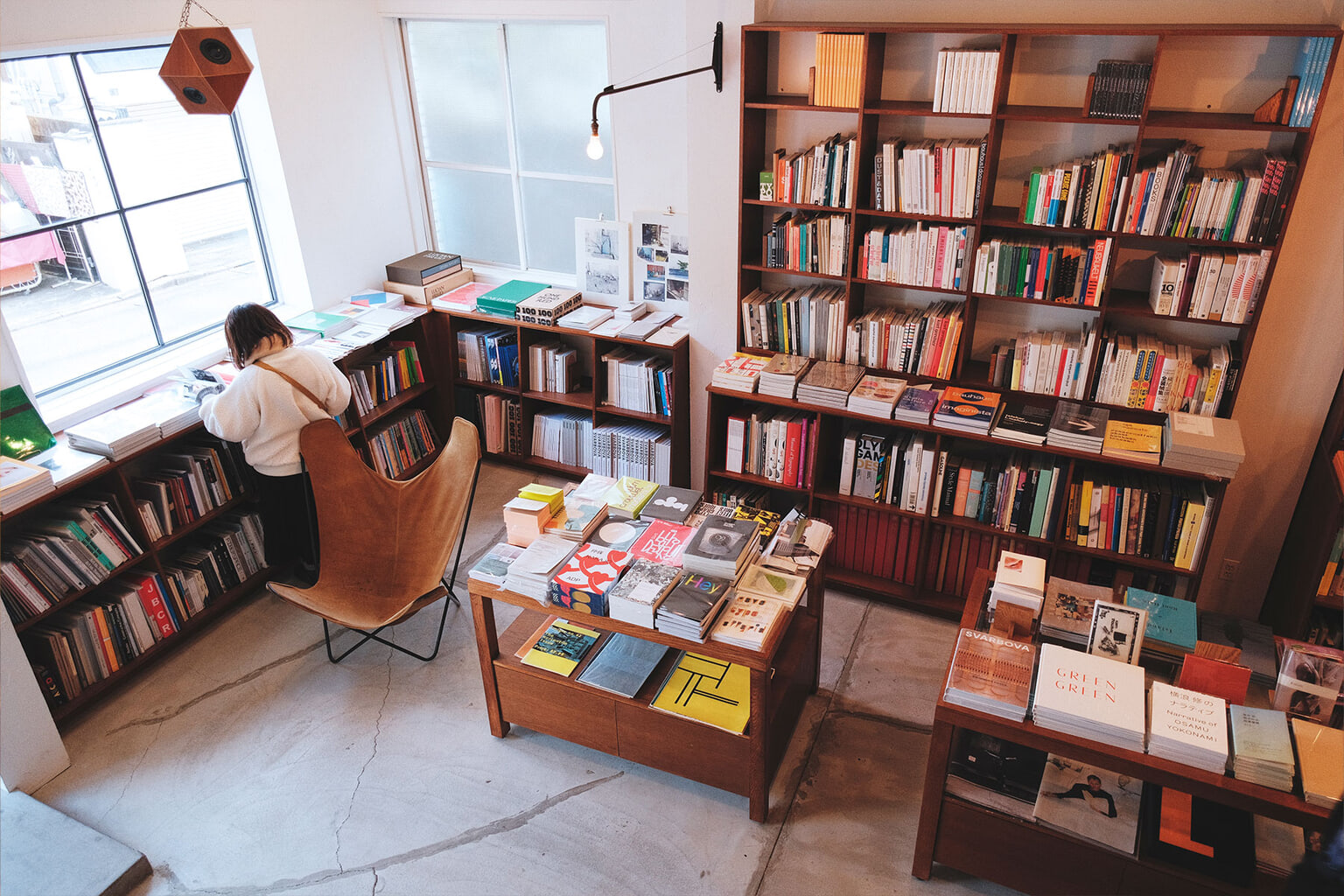

Established in 2014, Paper Crane Agency works to bridge the gap between Japanese titles and international readers. The agency’s specialization lies in introducing visual books, such as Japanese photography, art and children’s books, to publishers overseas, mainly in Europe and North America, for publication in translation.

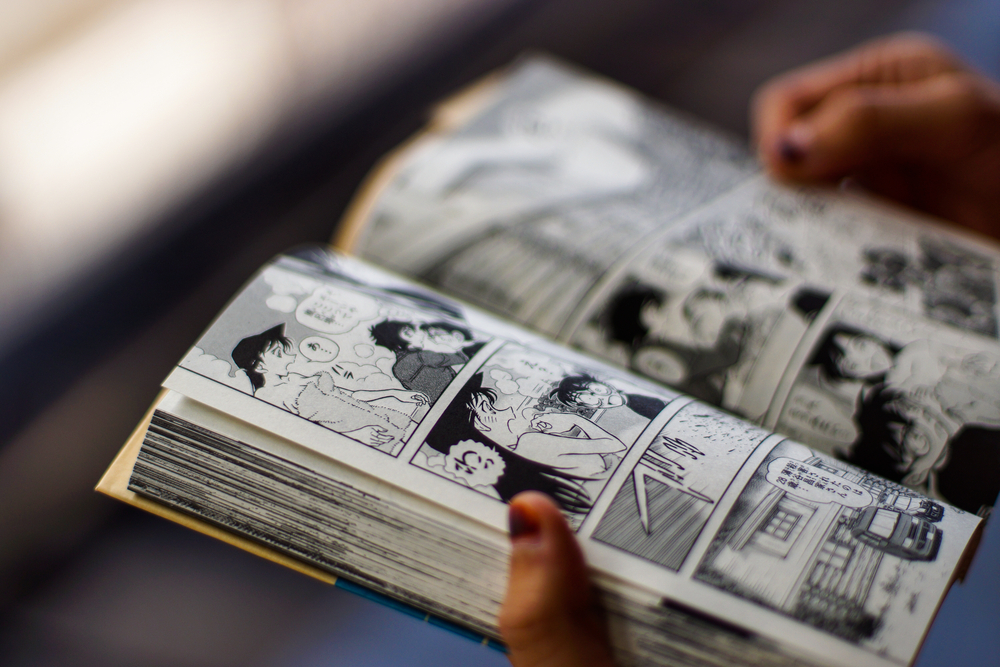

“In English-speaking countries, at least European culture, realist novels, and perhaps also narrative non-fiction and memoirs, are often seen as having higher cultural value, of being more ‘literary’ than other genres and illustrated books, especially comics and picture books, which are seen as primarily children’s genres,” says Williams. “This has been changing recently with the publication of many excellent graphic novels written in English, and the popularity of manga published in translation remains strong around the world.”

Photo by Stephan Jarvis

In Japan, It’s Paper First, Digital Second

Indeed, books in Japan are still a popular form of entertainment and way to consume information. It’s not uncommon to peruse the shelves of your local Tsutaya and find every manner of self-help, hobby or light novel covering everything from a guide on how to pitch a tent, to a story about how a homeless man reincarnates into a demon magician.

Williams notes that there has been a slight shift towards the e-format as she sees more and more read-off devices rather than the A6 bunkobon (pocket paperbacks) but not to the extent that you might see overseas.

“Printing houses in Japan actually receive a lot of protection from the government,” says Williams. “This allows them to stay competitive. There are also rules in place that deny e-commerce businesses like Rakuten and Amazon to not sell at a price lower than what is printed on the book. This may be way the traditional business model of books has been retained here”

Authors such as Haruki Murakami have become household names and inadvertently the archetype of what many would assume Japanese authors ‘sound’ like. While successes like this have opened up global interest in Japanese authors, Williams notes that it is important that artists represent themselves and don’t become synonymous with Japanese literature as a whole.

Mieko Kawakami

Japanese Literature at An All-Time High

“We have hit a critical mass in popularity with Japanese books,” says Williams. “This is probably thanks to the popularity of contemporary writers, such as Haruki Murakami and Yoko Ogawa, and classics by Yukio Mishima and Junichiro Tanizaki. […] More publishers are taking a chance with other writers, especially new writers.”

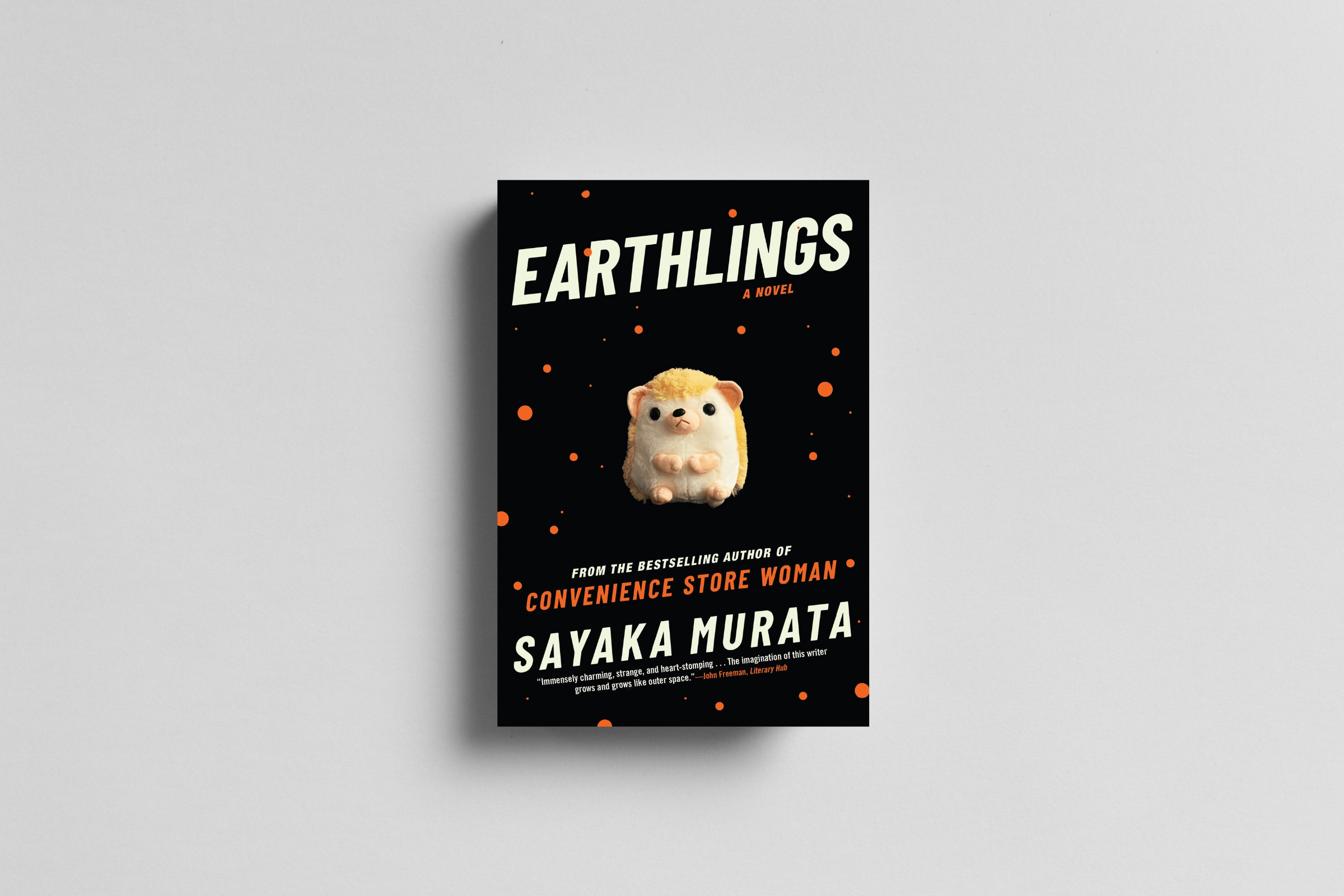

In recent years, readers abroad might have noticed more female authors hitting the shelves and being translated into English. Examples include Mieko Kawakami‘s Breast and Eggs (translated by David Boyd and Sam Bett) and Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman (translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori).

“These books are very different and cover topics that might not have appeared before,” says Williams. “On top of this, I’m seeing more women translators being given opportunities, and also translators more generally getting recognition for their role with their names featured on the book covers alongside the author’s name.”

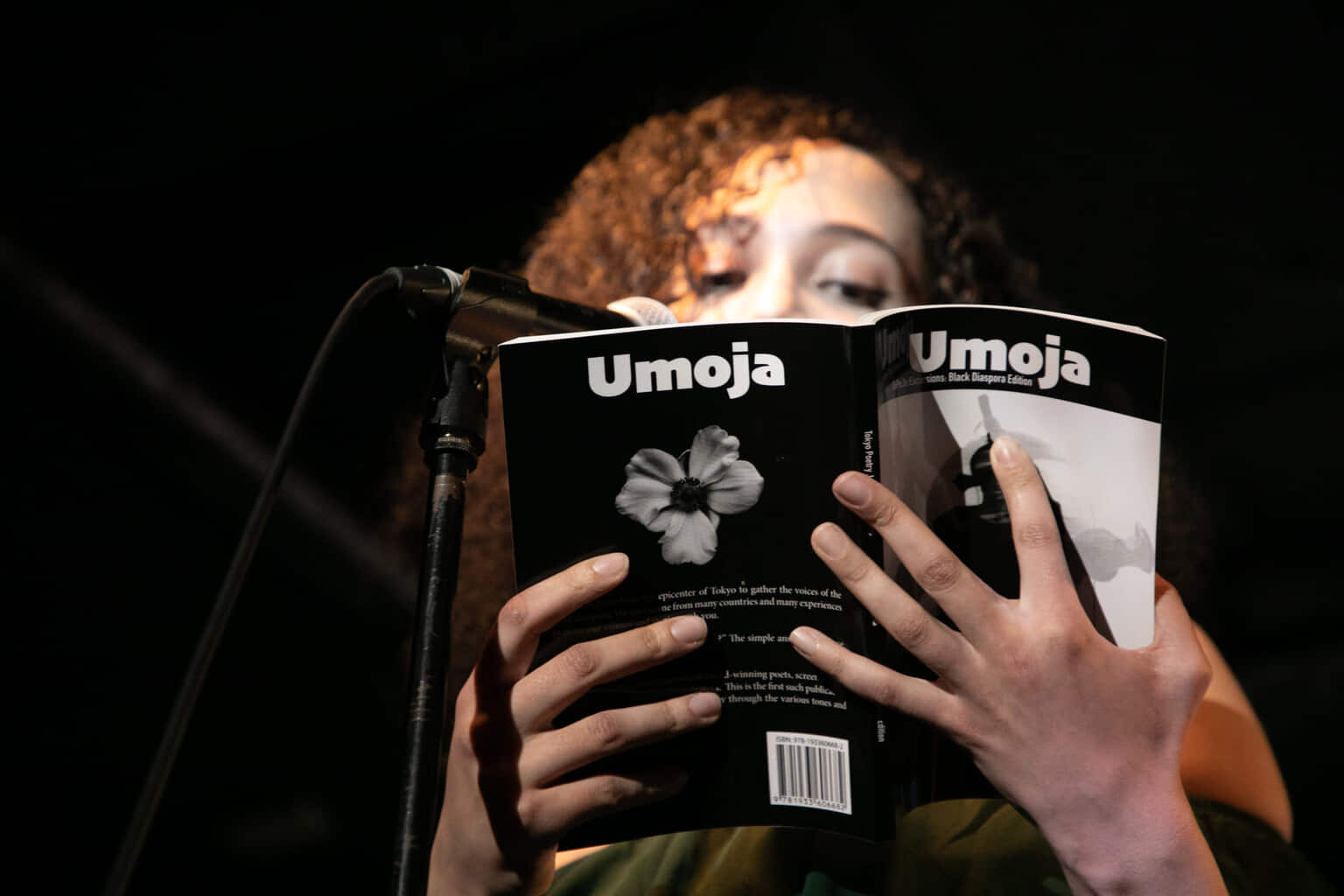

From the UMOJA live reading in February, 2022.

Foreign Residents as Japan Authors

The role that agencies play in translation, rights and distribution is crucial in painting the picture of a nation’s literary world. There is a growing movement of foreigners or non-Japanese who live in Japan and write. Giving them opportunities to share their voices will only showcase the sheer diversity that actually exists in this country.

“For Japanese works, these developments are thanks in part to literary magazines, such as Granta and Monkey, that support work published in translation, along with cultural foundations, such as the Nippon Foundation, which offers funding to publishers overseas who want to publish Japanese works in translation,” says Williams. “Tokyo Poetry Journal just launched their special edition UMOJA (ToPoJo Excursions: Black Diaspora Edition), which was edited by long-time Japan residents Biankah Bailey and Marcellus Nealy.”

Sayaka Murata’s Earthlings (translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori)

Considering her line of work, Williams isn’t unaccustomed to being asked for book recommendations. Rather than name specific books or authors, her biggest advice is to read translated versions of fiction or non-fiction. She’s currently reading The Books of Jacob by Olga Tokarczuk (translated from Polish by Jennifer Croft).

“There is no better way to access a new experience,” she says. “As you continue to read translated books, you’ll also begin to develop an appreciation for certain translators in how they handle language.”

For budding authors looking for their own agent representation, her biggest advice is to treat it the same way one would if it were a job application.

“Aspiring authors should research agents to find one who represents their kind of book and also target publishers doing the same kind of books, ” says Williams. “The query letter is like a cover letter for a job application and needs as much research and thought about where the book fits into the existing market. Pitching to publishers and agents is a lot like applying for a job, so make sure to put your best foot forward.”

For more information about Paper Crane Agency, visit www.papercrane.jp