When regaling someone with a tale from your past, especially one told on countless occasions, how much of it do you embellish? Does it get better on each retelling? Do you present yourself in a more favorable, or depending on the story, a more self-deprecating light? How much does your version of the story reflect the objective reality? Does that even matter?

Ryunosuke Akutagawa posed such questions to his readers 100 years ago in 1922, when his short story In a Grove was first published in the Japanese literary periodical, Shincho. Akutagawa, then a 29-year-old Tokyoite, was a master storyteller of the Taisho Era (1912-1926) and the soon-to-be-anointed Father of the Japanese Short Story. But few realized just how revolutionary the literary device he employed in In a Grove would become.

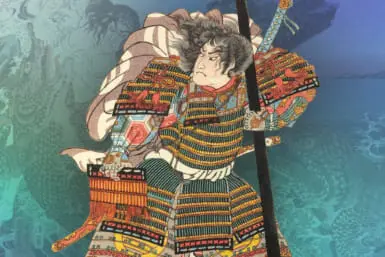

The story focuses on the murder of a samurai, Kanazawa no Takehiko, in a bamboo grove, and the conflicting accounts of multiple witnesses. Through the official testimonies of a woodcutter, a Buddhist priest, a policeman, and an old woman, respectively, we are treated to subtle differences in how each recalls the details of the crime.

The three principal characters – Tajomaru (the accused), Takehiko (the deceased, speaking through a medium), and his wife Masago (a victim and first-hand witness) – then give conflicting accounts of what transpired.

As layers of complexity are heaped upon one another (in a mere six pages, no less) readers are brought not towards a conclusion, but to draw their own. It questions the nature of truth itself and how it is bound by perspective.

So, what really happened to the samurai in that bamboo grove? The answer is, in a sense, immaterial.

Akira Kurosawa and The Rashomon Effect

In a Grove is better known, somewhat confusingly, as Rashomon, the 1950 Akira Kurosawa film which melded In a Grove and another of Akutagawa’s short stories (also called Rashomon) into one cinematic masterpiece. Some of the characters and settings differ, but the central plot remains.

Kurosawa’s Rashomon hit screens during the boom years of post-war Japanese cinema and was lauded upon release. It won a Golden Lion at the 1951 Venice Film Festival and an Honorary Award for “most outstanding foreign language film” at the following year’s Oscars. Using point-of-view camera angles for character testimonies and revisiting the same brutal scene on three separate occasions – each time colored by the narrator in question – it subverted standard filmmaking practice of the day by retaining the source material’s ambiguity.

From this film, which ensured Kurosawa became a global cinema darling, the “Rashomon effect” was born. It refers to unreliable narrators and conflicting accounts of the same event, and at its base level, is a phenomenon we experience daily. In fact, few human interactions are bereft of it.

Think of the last person you had an argument with and tell them how you remember it. Chances are your stories won’t align. But who is lying? Are both of your inherent biases reshaping the event? Have subjective and objective truths become conflated? Are you filling in the blanks with the most convenient information? And most importantly, who are we to believe?

When dealing with human experience, truth is messy and imperfect. This is what makes In a Grove and Rashomon so compelling. How the competing threads dangle in front of you and drive the conflict forward. How the stories reward revisiting to search for subtle details. How they appeal to our innate human curiosity. And how they keep you turning over the events in your head long after the final word has been uttered.

The Subsequent Influence of Rashomon in Film

The Rashomon effect is now common parlance across a range of disciplines, from filmmaking and novel writing to psychology and law. And as a storytelling tool it’s particularly effective.

Let’s take The Usual Suspects as an example. A hardboiled cop is grilling Roger “Verbal” Kint in the interrogation room. His goal: to figure out what happened during a massacre at the LA docks and to uncover the mystery of the mastermind known as Keyser Söze. Kint, who comes across as withdrawn and taciturn, is the sole recounter of the incident. We think we are experiencing the tale vicariously through him. He is our narrator. But are we right to trust him?

2014’s Gone Girl, originally a book by Gillian Flynn, also has nods to the Rashomon effect. It starts out as the story of a grieving husband turned chief suspect in the search for his missing wife – all the signs of a run-of-the-mill whodunnit. But when events are retold from a different perspective, audiences are forced to reevaluate their position on the central characters.

Quentin Tarantino has never shied away from Japanese influences either and the imprint of Kurosawa is littered throughout his filmography. In his first big hit, Reservoir Dogs, the color-coded cadre of jeweler store robbers are all cast into suspicion when it becomes clear there’s a rat in their midst. As they argue about what went wrong with the heist, in one of cinema’s most iconic warehouses, their misaligned perspectives spiral toward violent consequences.

What is Truth Anyway?

We like to think of truth as absolute. But the Rashomon effect shows that our notions of truth are flawed and ultimately self-serving. And though it may seem a cynical view of the world, Kurosawa’s interlocutors put it best:

“Damn it,” said the Woodcutter. “Everyone is selfish and dishonest.”

“If we don’t trust each other, this earth might as well be hell,” opined the Priest.

“It’s human to lie,” said the Commoner. “Most of the time we can’t even be honest with ourselves.”