Until a few days ago, it seemed genteel, quaint even, that Japanese politicians could give campaign speeches on street corners and freely shake the hands of passersby. That Japan was so safe a society the need for excess security during a public appearance by the longest-serving prime minister of the modern era was deemed superfluous.

In the wake of Shinzo Abe’s assassination, however, one must question if it’s time for change.

I was in the UK when I heard the news. Waking up rather bleary-eyed, I switched on the TV and was startled awake by the images presented to me.

Though I have commented on Abe, his lineage and his former administration’s policies in less than favorable terms, watching one of the most influential Japanese statesmen of his generation gunned down in broad daylight was a harrowing experience.

The geopolitical rhetoric has focused on the barbarism of the crime; painting it as an attack on democracy itself. And while this rings true, it could also reframe Japan’s notions of domestic security.

The Show Must Go On

In the aftermath of the shooting, a visibly shaken Fumio Kishida called his Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) campaign ministers back to Tokyo. He was then back on the trail with heightened security on Saturday, including a metal detector at one of the locations, while other major parties held back senior figures from public rallies on the eve of the Japanese House of Councillors election.

But in a vow to uphold the democratic process, and in a defiant stance against violence, campaigning largely continued. Curiously, in some quarters, it was business as usual, with images of politicians fist-bumping members of the electorate and smiling for selfies less than 24 hours after Abe was pronounced dead.

But the friendly veneer of Saturday campaigning obscures a darker reality. An armed gunman was able to get within three meters of a stumping politician — and to fire two unanswered shots almost three seconds apart — before security stepped in. Japan needs to understand how and why this was able to happen.

Who Was The Lone(ly) Gunman?

The initial speculation centered around assailant Tetsuya Yamagami’s possible objections to Abe’s vision of redrawing Japan’s pacifist constitution — namely, Article 9, which states that Japan forgo all wartime potential — or his continued influence on Japan’s domestic economic policy.

Reports have revealed the act was more personally motivated: Yamagami claimed Abe supported a religious group that had bankrupted his family. Although police have yet to disclose the name of the group, investigations have shown Yamagami’s mother was a member of the Unification Church, a cult-like outfit with an estimated 300,000 members in Japan and financial interests in various sectors of society. Reports suggest she also donated a significant amount of money to its cause 20 years ago.

The Unification Church was founded by Korean Sun Myung Moon and was reportedly introduced to Japan by Abe’s grandfather, the bloodthirsty former prime minister, Nobusuke Kishi. The story goes that Moon and Kishi hit it off through shared anti-communist sentiment, and a familial connection to the church was passed down through the generations, with Abe sending a congratulatory video message to the group as recently as last September.

The strangeness of the crime didn’t stop at the motive. Yamagami, a former member of Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Force, used a handmade gun, constructed using metal pipes and tape as though he had foraged materials in an apocalyptic wasteland.

This is partly because guns are difficult to come by in Japan, with strict prohibitions in the legislature dating back to 1958. There are estimated to be 0.3 guns per 100 of the population, due to strict procedures that vet applicants’ mental health, drug-use habits and criminal records. Applicants must also pass written tests, annual gun checks by police and fork out hefty sums for licensing, permit and taxation. Even Yakuza gangsters favor knives, as the penalties for illegal possession of firearms — up to 15 years imprisonment and huge fines — are deemed too severe to be worth the risk. All this has contributed to fewer than 10 gun-related deaths annually in Japan, a country with a population of over 120 million.

A Worrying Trend?

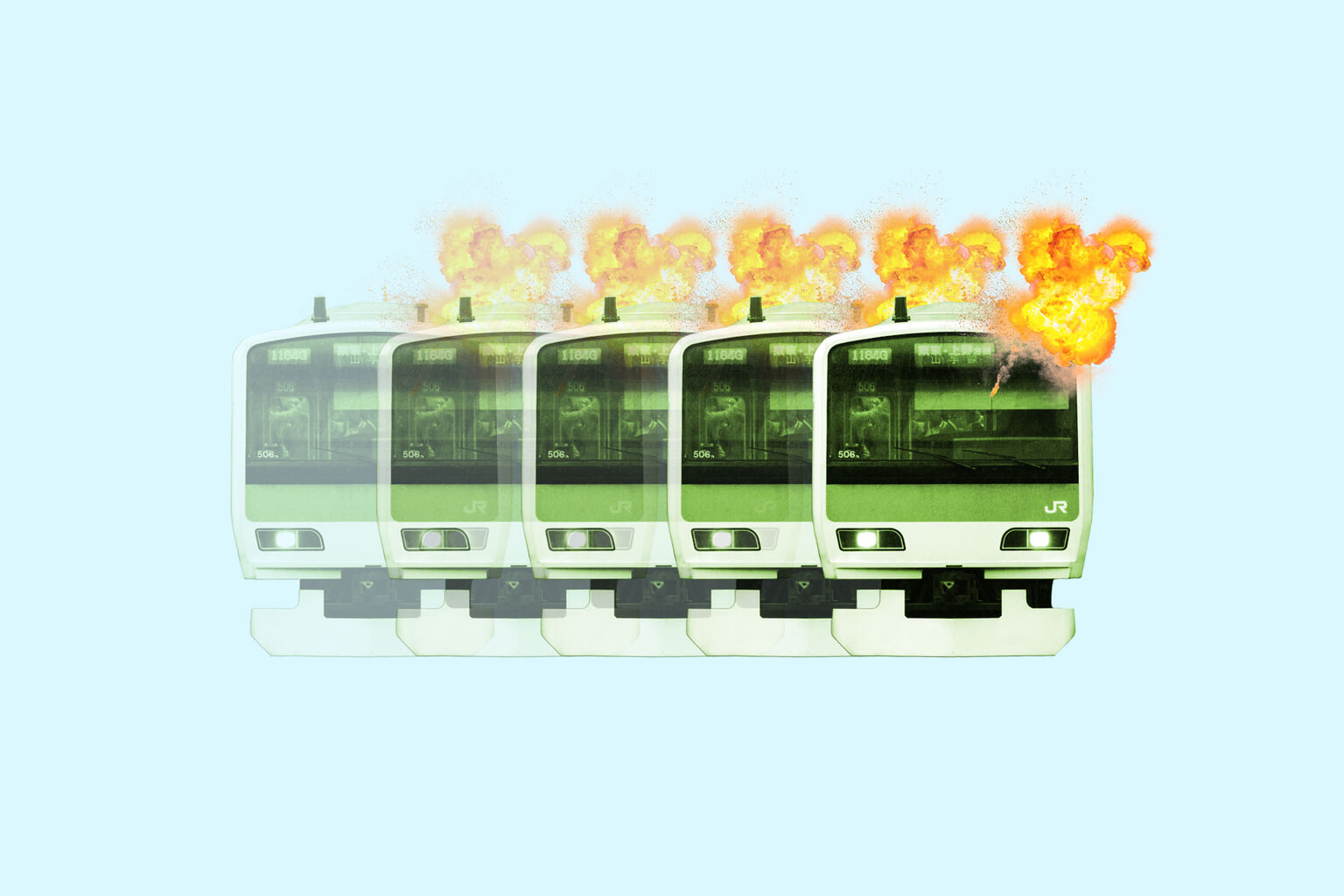

This is not the first violent crime in Japan to capture international headlines in recent years, but whether parallels can be drawn is still up for debate. In August last year, a knife-wielding perpetrator, who hoped to “kill any women who looked happy,” injured 10 on the Tokyo-Kanagawa Odakyu Line. Then in October, a man dressed as the Joker went on a slashing and burning frenzy, injuring 17 and spawning a copycat attack on a Shinkansen in Kyushu days later. Two deadlier attacks took place in 2019, with a knifing spree in the Tokyo suburbs that killed two and an arson attack on an animation studio in Kyoto with a body count of 36.

If there’s a pattern emerging, it’s this: the lonely, disaffected male lashing out against a perceived oppressor. And while it is all relative — the US, for example, experiences tens of thousands of gun deaths annually with regular sprees carried out by suicidal young males who’ve authored Unabomber-like manifestoes — there are consistent social factors present in the offenders.

Security Woes

One of the major benefits of living in Japan is that personal safety is taken as a given. Despite being the world’s most populous city, Tokyo consistently ranks as the safest with crime rates low across the board. In fact, prior to Shinzo Abe, Japan Socialist Party leader Inejiro Asanuma, stabbed to death in 1960, was the only assassination of a key political figure in the post-war era in Japan’s capital.

Lax security at political events has become the norm: only one specialized police officer was believed to have been in attendance during Abe’s assassination alongside a handful of officers tasked with crowd control. Furthermore, local police deal with such few instances of violent crime that they have little in-the-trenches experience. Were more of them on the scene, there’s no guarantee they could have prevented the situation before it escalated.

It’s a saddening truth that these once-intimate public appearances may evolve into rigorously garrisoned events. But when the dust has settled, the assassination of Shinzo Abe will continue to serve as a cautionary tale.