Labeling Ryuji Fujimura as “an architect” doesn’t seem to do him justice. Of course, he has headed his own very successful business, Ryuji Fujimura Architects (RFA), since 2005 but he has evolved into and embodies several other roles including teacher, curator, community builder, writer, editor and, perhaps, most importantly — philosophical visionary.

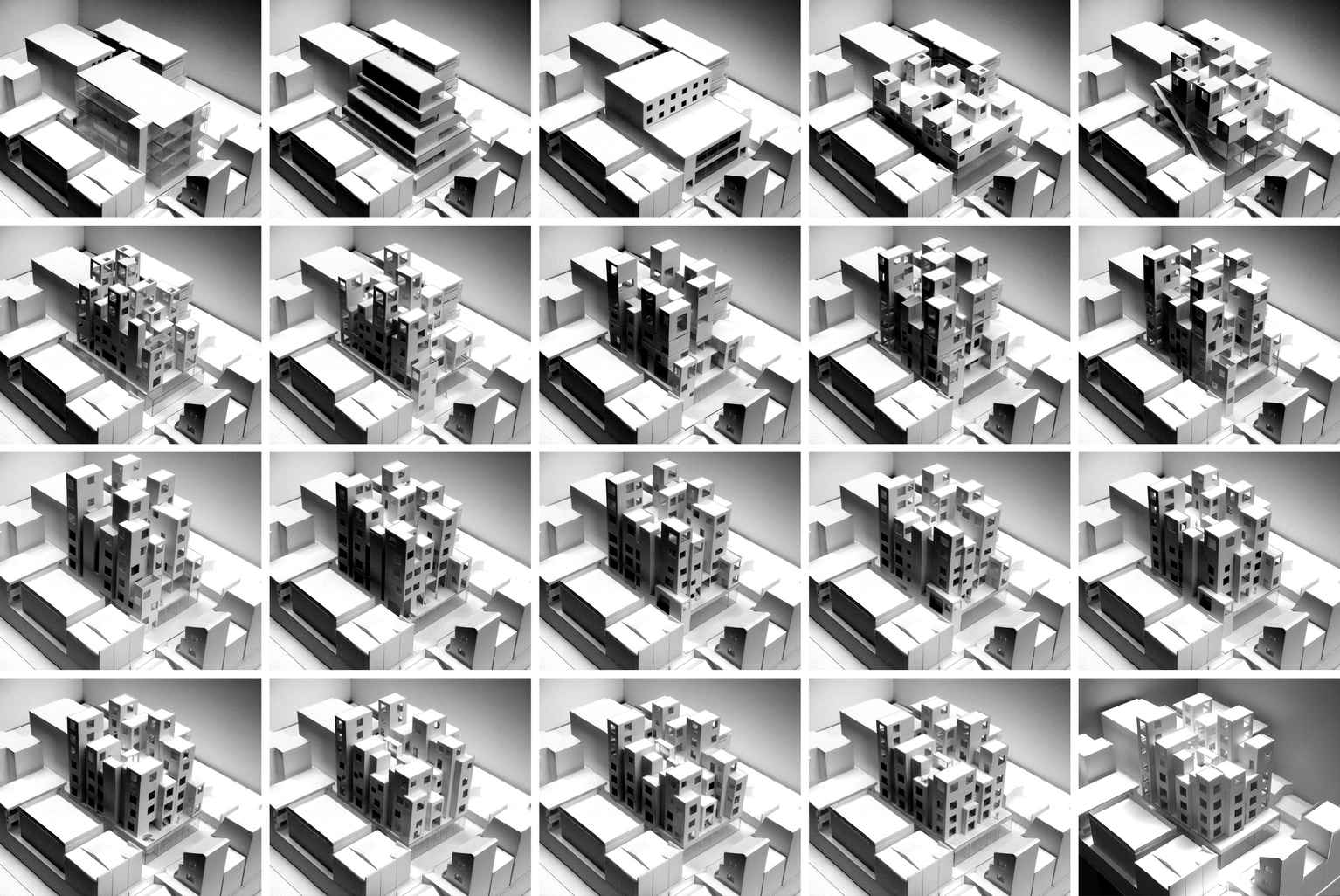

When I meet the youthful 45-year-old Fujimura at his architecture firm’s office in Ueno, he greets me outside, clad in Comme des Garçons, with a firm handshake and ushers me inside where giant architectural models from his projects are visible, hundreds of books line the company’s shelves with a faint murmur of chat emanating from other parts of the office that floats delicately in the background. We drink cold tea, it’s unbearably humid outside on this particular early summer’s day, sit down and for more than an hour he dazzles me with his vision for architecture, the role that this discipline can play in building and strengthening communities, his commentary on the spatial evolution of Tokyo and several other topics that blend effortlessly into each other. He’s funny too and we laugh, talk of mutual acquaintances and then get down to the business at hand.

A Communal Calling

The word “communities” comes up regularly when speaking with Fujimura. And it’s unsurprising as he works and has worked with communities all over the country. I ask, as an opening gambit, if community and architecture, for him, are “inextricably linked?”

“Architecture and design depend on community and pretty much community depends on architecture,” says Fujimura. “They heal each other. When architecture heals, community heals and vice versa. When I design something or propose something we need to approach the community as well. It kind of started in California in the late 1960s, I think. In Japan we had a kind of community movement, but this is a more sophisticated way of designing with the community called ‘community design’ and then it was imported to Japan in the late 90s and one of my professors at university was responsible for this. The places involved were in Setagaya (Tokyo) and Kobe, kind of community developments and for the last 20 years this kind of project has spread all over Japan. We need people to solve the many difficult issues we face like an aging society and empty houses. After the earthquake in 2011, this was another starting point to change our thinking about this.”

When speaking with Fujimura, it’s clear that working within communal structures and state-sponsored projects is essential and critical. His weltanschauung, it could be said, centers around the Japanese version of community town planning named “machizukuri” in which the central pillars are to bond, bridge and create communities who aim to be involved in government decision-making. Machizukuri utilizes techniques such as town meetings, consensus building, negotiation, information and opinion sharing and forms of local leadership.

Subaru Nursery

One of RFA’s most distinguished projects which encompasses this kind of thinking is Subaru Nursery in Kumamoto Prefecture. “After the earthquake in Kumamoto in 2016, we had to think about making strong shelters for people,” comments Fujimura. “The Subaru nursery which I designed had all of this in mind — the basics of strong architecture. Our proposal for Subaru was actually quite simple. It’s a little bit unique and cute. The shape of the architecture, by chance, is the same as the surrounding mountains. It symbolizes their local pride. This nursery school or elderly care facilities, they are all welfare institutes and actually the Japanese government is trying to expand this kind of project and activity in order to solve the various problems like the lack of young people and elderly people who have to be cared for.”

The official notes on the magical Subaru Nursery can be found on RFA’s superbly detailed website.

Subaru Nursery

“When we visited the site,” writes Fujimura, “there was an adjoining sacred grove of a local shrine on the west side, and one can enjoy a panoramic view of the vast expanse of rice fields with Hanatate Mountain and the continuous mountain range in the distance towards the northeast direction. I felt that we needed to carefully consider how to connect these surroundings with the nursery school building.

“The view of the mountains in the distance, framed by the horizontal ribbon windows, appears very close,” he continues. “When seen from the outside, the undulating roof shape generated using a machine language of algorithmic design and the shape of Hanatate Mountain formed by the force of nature overlap each other to create a continuous scenery where the architecture merges into the surrounding landscape. I was convinced that we successfully realized the idea of ‘architecture as a continuous body’ that becomes one with abundant nature.”

AI and the Future of Architecture

Our conversations turn to the use of AI in design and my eyes catch a particularly unorthodox chair which sits just over my right shoulder in Fujimura’s office. Resembling a huge marshmallow or a sedentary version of cartoon character Baymax, it turns out that this chair is Fujimura’s now renowned Deep Learning Chair which caused a bit of fuss on the internet a few years back. And here it is, just a few meters away from me.

“Using Google’s image search, I input the word ‘chair’ in various languages, nine languages in total,” explains Fujimura. “Every result was different. If I input the word ‘chair’ in English Google shows us an ‘English chair’ and in Chinese a ‘Chinese’ chair and so on. I collated all the images and then AI learned those images. Finally, I integrated all of them and we came up with a chair for humans. The message is if I use this kind of AI chair it’s not an average value. AI learns the essence and features of each kind of chair. AI learns the uniqueness of each chair. The final shape of this chair isn’t the result of combining the average, it’s the culmination of the individuality and idiosyncrasies of each culture.”

Deep Learning Chair

The Evolving Metropolis

When we talk of AI, technology and the future of architecture, the conversation naturally and quickly turns to Tokyo and its current new phases of growth. Protean, elusive and energetic, the Japanese capital is undergoing a new era of transformation with major developments taking place from Toranomon and Shinjuku to Shibuya and Yaesu. I’m interested in what Fujimura has to say about the city in which he works and lives.

“We had a peak of construction and investment in the 1960s but what we’re seeing now is a second peak,” says Fujimura. “Tokyo is a natural metabolic city. It transforms and over the last 25 years has transformed extremely. Before that there was a lost age after the bubble economy. After that the government decided to change the law and tried to reactivate the construction industry on a large scale in some special designated areas such as Roppongi and Marunouchi. And due to that lots of construction has occurred since around 2005. Prime Minister (Keizo) Obuchi and later (Junichiro) Koizumi changed the regulations in place and that, in turn, accelerated the construction seen in the city.”

It seems, however, that as we sit in a very historical nook of Ueno with nearby, almost hidden shrines and discreet homes with dense foliage sprouting onto the sidewalks, that in some ways Tokyo hasn’t changed at all. This is the greatest dichotomy of Tokyo, it changes its face and throws on some gladrags but deep down, it’s ostensibly the same.

Subaru Nursery

Town and the Country

As our conversation comes to a close, I ask Fujimura about his current and future projects. Animated and engaged, he talks firstly of an intriguing project in the mountains of Nara which is renowned for its quality local wood. RFA is designing a village office or small town hall for its residents which has an issue of a severely aging population.

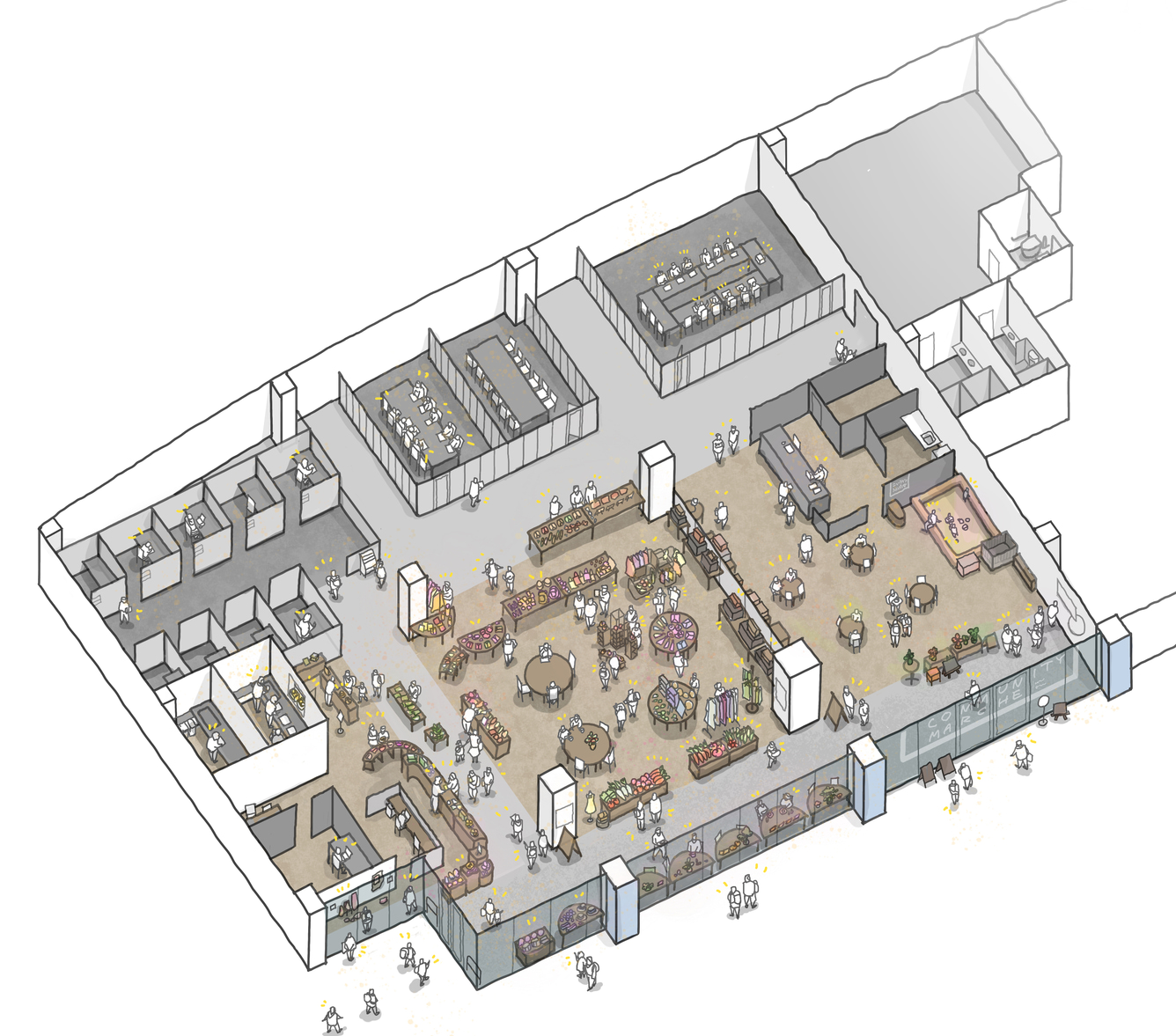

The second project mentioned is a new community space in the suburbs of Nagoya which sees Fujimura draw on similar experiences he had when working on his Hatoyama House project in the suburbs of Tokyo in 2019. Hatoyama House was a project to renovate and transform an empty house into a shared house for students in a new town in the suburbs of Tokyo where the aging rate exceeds 50 percent. Commissioned by the town government, RFA searched for vacant houses, negotiated with owners and designed the renovation, and continues to help with operations after its completion.

“In Nagoya however, the clients are doctors who are interested in community development,” says Fujimura. “They want to be involved with local people and I helped them. They decided to make a kind of forest and planted saplings and then they put special soil so the trees could grow bigger and faster than usual. After five years they created a forest in the field. And after that, they want to add architectural projects within the forest. Usually there is a field, then we put architecture then a forest. But this time the community will be first and then they will build the forest and then that can attract other people to the area. It’s good for families and children to be involved in this community practice.”

Collectivity, a sense of community, the use of cutting-edge technology and theory, and the future of architecture and urban and rural spaces all concern Fujimura, who walks me out to the front of his office. Charming and humble, the architect and social visionary continues to talk design and architecture and I wonder about the future of Japan and how it will be able to integrate all these contexts and concepts into a better future, a future where community supersedes solipsism and where we can build and expand into an even greater life.