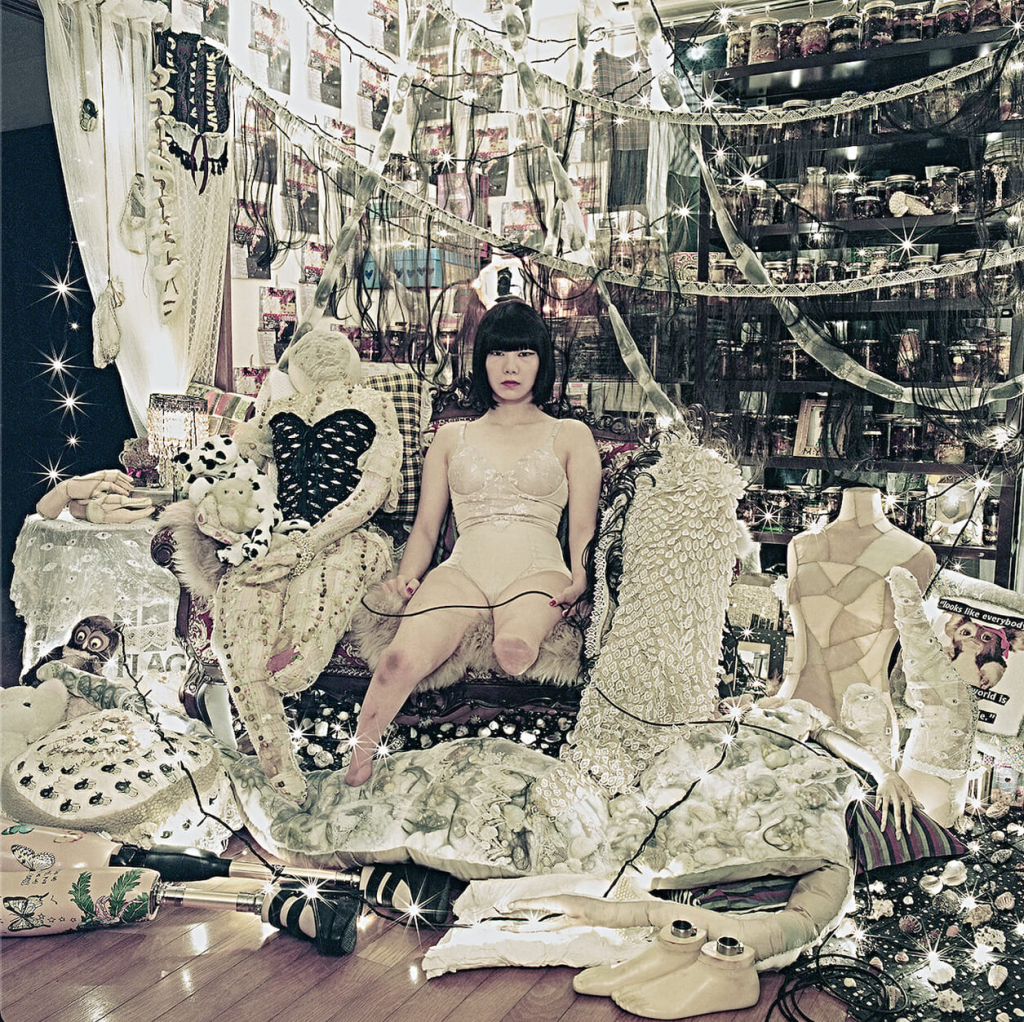

With dark eyes, Mari Katayama stares out from her works, defiant and stern as both the observed and the observer. So it is a pleasant surprise when we talk and she is jovial, even funny, and open.

Katayama was born with tibial hemimelia and had both legs amputated as a child. Her deeply personal artworks, which often place her as the subject, allow the viewer a glimpse into her own, deliberately constructed mise-en-scene, placing her as a doll within certain conceived situations. As a double amputee, her portraits strike an exceptionally powerful chord within audiences across the globe.

Since gaining recognition at the age of 17 in the biennale in her hometown of Gunma, she has exhibited at renowned shows worldwide including Venice Biennale, Maison Européenne de la Photographie (Paris) and White Rainbow (London). She also received the prestigious Ihei Kimura Award for ‘Gift’ (2019).

(c) Mari Katayama bystander #014

(c) Mari Katayama bystander #014

Lithuanian Rivers Are Different

When we speak, Katayama has just returned from her first visit to Lithuania, enthusing about the kind people and the environment. She was there to oversee the installation of her exhibition at Kaunas Gallery, which revolves around rivers and their perpetual cycle.

She realized the importance of rivers to her narrative after returning to her hometown in 2014. “I became conscious of the existence of rivers in relation to our daily lives,” she tells TW. “The water cycle: rain flows into the river, and the river flows from the mountains into the sea. And from that ocean, clouds form again, and those clouds become rain. The cycle is perpetually repeated, yet the action is not exactly the same every time. I feel that it is an important way of learning about ourselves.”

(c) Mari Katayama shadow puppet #001

But she was met with confusion: “When I explained it to the interpreter, she said: ‘Yes, the river runs through Lithuania, but we aren’t really conscious of that cycle.’” At the time, the artist was surprised. Growing up on the Japanese archipelago, all rivers lead to the sea.

Upon a visit to Kaliningrad in Russia on the final day of her trip, she realized what the interpreter meant. Lithuania, at the heart of Europe, is different. “We drove to the very last point we could get to, and then walked down the river to the closest point we could reach when I realized… The destination of that river is Russia. There is a lot of history, and you can’t just sum it up as a circular process. People have been destroying, breaking, and building with their own hands.”

(c) Mari Katayama bystander #001

Wanting to Fit In

It is well documented that Katayama decided, at the tender age of nine, to have her legs amputated. TW asked what she was like. “I was a difficult child. I could never commit to a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer,” she says. In Japan, where society is conditioned to keep heads down and not to ask questions, this trait proved trying. “I was a right nuisance,” she adds laughing.

Even so, she did have a desire to fit in. “At the time I decided to get my legs amputated, it didn’t seem like such a big decision,” recalls Katayama. “I just wanted to wear the same shoes as everyone else. When my legs were amputated, I think I understood that actually I would never be able to be like everyone else.” A tough realization for a nine-year-old.

(c) Mari Katayama just one of those things #002

Disability in a Social Context

For a developed country, Japan has a notably large stigma around disability. In Katayama’s case, when reporting bullying at school, a teacher purportedly said that she “provoked bullies with her eyes.” We asked if she could see a similar thing occurring in today’s climate. “I think there will always be prejudice against children with disabilities,” she replies. A bleak outlook, but one that she justifies through a couple of factors, namely: society and education.

Interestingly, she does not hold the people who discriminate responsible, stating. “Unless we instigate change within our social environment which makes it unacceptable to discriminate, the situation will continue.”

Recently, there has been more movement toward policies for the disabled. In January 2014, four months after the Olympic announcement, Japan became the 140th country to ratify the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities which led to around 3,000 new policies.

Katayama comments: “[Around the Paralympics] there was a Japanese TV program which showed the lives of Paralympians, but it finished, which makes it seem like these people only existed during that special time.”

(c) Mari Katayama leave taking #003

Leaving Things Open to Interpretation

In ‘Gift,’ Simon Baker makes the comment that Katayama “Constructs objects, environments, photographs and even frames” and there have been other references where Katayama created in order to take ownership of a certain narrative. To what extent does she like to control a situation?

“On the contrary, I like to leave things open to interpretation,” she says.” For instance [holds up a bottle] what if I tell you that this is whisky?” The brown liquid inside could indeed be whisky. “I don’t like to tell people what to think.”

“This probably stems from my undergraduate days,” continues Katayama. “Even though I didn’t study art with the intention of becoming an artist, art was a good outlet. I wanted to fit in and be ‘normal,’ but I wasn’t.”

For someone who seems like they were born to create, it’s surprising to hear that Katayama didn’t study art to become an artist.

“In the end, I simply realized I couldn’t do anything else,” she says. Unfortunately, the reason for this is not as romantic as it may appear. “Just yesterday I was looking into the average wage for disabled jobs in my locality. It’s ¥100,000 per month. We live in a system of ‘we’re giving people with disabilities the opportunity to work’ which is where the problem lies. We aren’t treated the same way as the rest of society.”

(c) Mari Katayama shell, 2016

A Sad Fact of Living with a Disability

An oft-told story about Katayama is that she dyed her hair green and wore short skirts while at school, but what was the most memorable thing she did to rebel? “Having a daughter,” she answers. “Everyone was against it. Not that I had a child to rebel, of course. But in my life so far, even compared to becoming an artist, giving birth was the thing that most people were against.”

Her family frequently asked: ‘When are you having children?” From others, however, she received a lot of negativity. It becomes clearer why Katayama says that she doesn’t think discrimination against people with disabilities will end.

Tough Love for Prostheses

Katayama reveals that she actually hates having prostheses, but has recently come to something of a truce, with the adoption of an electronic knee joint.

“[Prosthetics has] been the hardest part of my life,” admits Katayama. “Some people say that wearing a prosthesis is part of the body, but for me, it feels like wearing a very heavy boot.” It’s a catch-22 situation: “I hate prostheses, but I can’t live without them,” she says. “And I can’t function in society without them either.”

After making the switch to an electronic prosthesis for her knee, she has a newfound joy in walking again. “I’ve recently come to realize that I need to build my own body in order to utilize this electronic prosthesis. I’ve begun to enjoy it, as the more I work at it, the nicer my gait becomes,” says the artist.

(c) Mari Katayama bystander #023

High Heel Project

Something else that improved her outlook further was collaborating with famed Italian shoe designer, Sergio Rossi, on the High Heel Project (HHP).

The aim of HHP is to show others that they have the power to choose, by creating high heels for prostheses. Katayama sang on stage and gave talks, while wearing the fashionable high heels that she made for herself.

She started the project in 2011 while at university, as she wanted to do something more than become an artist. “My role as an artist takes over, but with HHP, it’s easier to connect and interact with people,” she says. “Of course, I can understand the bigger picture but I can’t see how it’s going to evolve and I don’t have full control.”

After a short hiatus, the project is restarting for 2022, through a lauded collaboration with Rossi, who holds the philosophy “shoes are an extension of a woman’s legs.”

“I feel that we have that shared image, as I am also making a body to a certain extent,” says Katayama. She also wonders if the recent societal changes regarding those with disabilities may have been an unconscious factor in restarting the project.

(c) Mari Katayama, on the way home #005

We Are All Lucky

‘On the way home #001’ (2016) looks like a fantastic haute couture garment. However, Katayama is realistic, admitting, “I like sewing but I could never make clothes. Originally I wanted to work in fashion but around the age of 16 I realized I had no sense for it and gave up on it. So that is completely out of my head, for now and forever.”

TW is impressed that someone could be so decisive but Katayama is frank. “I think knowing when to give up is very important.”

In ‘Gift’ Katayama says she considers herself lucky for the body she was given. She tells TW: “I think everyone is lucky whether they realize it or not. No matter what kind of body we are born with, the fact that we are living in this world is lucky. We are here, we can feel, we can cook, we can eat, we can think; I think that’s a great thing.”

Future Plans

When asked about future plans, she is excited about a number of things, mentioning her passion for film, an exhibition in Italy and the work she began in Lithuania. “I’d like to go back to Lithuania in Autumn. That’s not actually decided yet but I’m determined to get there! I’m already getting excited planning it.”

Mari Katayama restarted the High Heel Project in 2022.