Finding new ice climbing routes demands patience, nerve, and more than a little luck – and all that is before you even begin your ascent…

By Ed Hannam

With its early starts, strange equipment and inherent dangers, ice climbing will never be more than a fringe sport. Only a few months a year conjure up the right conditions for ice to form, climbing time doesn’t always line up with available time, and just when it starts getting good the season starts to end. Changes in the weather can upset entire winters with too much snow or not enough of it. Rain and sun combine unpredictably, and it can be years between the time when reliable ice forms in some areas. Add this all up and very few climbers who start out on indoor walls will ever end up climbing ice because it’s simply too much hassle.

After spending years climbing in the better known areas around Japan, a whisper had emerged from some older climbers about a forgotten place “up north.” Apparently decades before the hard men and women of the time had found amazing ice features and put up a dozen or so difficult routes. As opinion had it, this was their undoing – the routes were too hard for most climbers of the day to repeat, and so it remained the stuff of legend, an ice climbing El Dorado. Any more searches turned up nothing aside from a hazy photo or two and a vague map with little detail.

A short trip to the area (let’s call it Yamagata) brought us into contact with shy locals who vaguely recalled climbers going there years ago, but it had been silent a long time. The only clear discussion we had was with the owner of a decaying onsen who reckoned that, as the roads were cleared of snow less frequently, everything out there – including his onsen – was winding down. Along with this uninspiring news he told us that the season for ice was only when the direction of the wind sent temperatures way down, and that period had already come and gone a few weeks before.

After a long year of keeping things quiet we returned, timing things for the window of cold. Pulling into the verge at the end of the road, our headlights illuminated old buildings, all closed and shuttered. Beyond, the road was covered with settled snow. No footprints were visible. There was no reason at all for anyone to be there, so we pitched our tent in the eerie, howling darkness and got our gear ready for the morning.

Skiers dream of bright blue mornings and ice climbers do too, but they really understand that dull and overcast is better, as it has less effect on the ice. The following morning granted us that. By torchlight we ate, drank coffee and emerged from the tent, heaved on our packs and started down into the valley. It was certainly cold as we walked into the wind that howled from across the mountains, creating the rush of freezing air. It was a bittersweet trade off that we hoped was worth it.

The valleys were narrow and the walls were multi-tiered, meaning little sun crossed the faces, and unique rock formations made channels for ice to collect and grow in. To be “good,” ice has to be uniformly formed, well bonded to the rock beneath, and protected from direct sun that can break it down. Tight, tiered valleys that catch the snow are ideal for this.

“When done well, ice climbing has a unique dynamic, more tai chi than brute force … it is a beautiful but totally unnatural thing to do.”

The winding geography of the valley meant we could only see small parts of the walls above us, and through the purple pre-dawn light we began to get a notion of what was around us. The walls were covered in jewel-like ice that encrusted the rocks’ features to form chandeliers and pillars that drooled down the cliffs and hung from the roofs of caves. We found the ice to be exceptionally clear, hard and well bonded to the volcanic rock beneath. The rumors of the area being left to obscurity due to lack of capable climbers began to seem true: in fact, by the look of it, the old crew had barely gotten started. With the majority of the walls either non-existent on the old maps or barely recorded, for every ice line mentioned we counted another seven or eight not.

Deciding on a route to climb is always hard and when there are hundreds of choices and you’re working against dwindling time, things only get harder. Lines were everywhere but most looked exceedingly tough—the stuff of days to work at. Our time in the valleys had shown us that nothing was going to be easy, so the idea of just taking a token route was off the table. We decided elegance would give us the right options, and something truly worthy of shooting for—even if we failed. We went for a line of thin, intricately chandeliered icicles that wove up the back of a corner in the rock face. Unlike many lines, this had ice to ground level rather than starting with an overhang.

Your protection from falling are threaded titanium tubes that have been screwed into the ice and clipped to ropes. Ideally a screw gets placed every five or six meters but in reality it is wherever you can get one in. Fat ice lets you drive the screws deep, but thin ice demands total attention. It’s a matter of delicately picking away, being careful to not drive into the rock beneath. Over the 50 meters of a pitch this is exhausting, nerve frazzling and totally absorbing. The irony is that the effort of placing these screws makes a fall more likely. The fact that many ice lines can be easily climbed but not made safe is fundamentally accepted by ice climbers, and is exactly what we had going on.

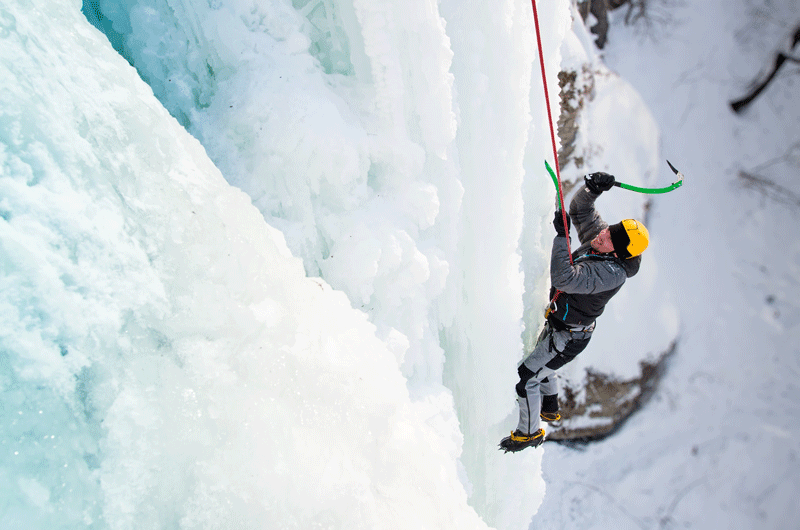

My initial fear quickly became total concentration as I picked my way up the wall of ice crystal, smashing away anything threatening in a constant cascade of tinkling ice shards. In the silence of a frozen valley, ice climbing can sound amazingly violent as every foot and tool placement means smashing into fragile ice. Ice is inherently frictionless, so your only connection to it are the points of metal. This makes those pick choices very important and involves a process of reaching high, swinging with careful force and weighting the tool to make sure it holds.

Image: Shutterstock

The line of ice topped out at a large ledge that was safe to stand on, and to our surprise diverted to form several more ice falls up tiers of overhanging rock above. Burned out from what we’d already done, we left them for another day, and named the new line Shimajiro after a popular kids’ toy, and the face itself White Dragon Wall. As we rappelled back to the snow line the afternoon snow began to thicken and clouds rolled down the valley.

We spent several days in the various valleys trying out new lines: some worked out and others did not. Each day we would return exhausted and cold but high on the idea we were climbing new ground, a buzz that gets rarer every year.

Since then we have returned every winter, silently keeping the dates all year. In keeping with the attitude of the locals we haven’t pushed the location into common awareness; the roadside verge is still empty, the road still uncleared. The old onsen has never reopened. We prefer it this way: In a world of oversaturation not everywhere needs to be on the map.

Ed Hannam is a strategy analyst for Tokyo-based Tripleshot Consulting, which has a long history of working in complex and dangerous environments. He also runs iceclimbingjapan.com.

Main Image: Shutterstock