It’s a 232-year-old cookbook that outlines more than 100 egg-based recipes.

But Manbō ryōri himitsubako, or Secret Treasure Chest of Ten-Thousand Recipes, is no longer just a dusty old relic. This is one of numerous Edo period books that have been converted to digital format and have helped to inspire a selection of Japanese food that will soon be served up to visitors at a Tokyo department store.

Spit-roasted eel will be available for ¥1,404 from the Idumoya retailer within Mitsukoshi Nihombashi. Since the Edo period, grilled eels have been a popular dish in Japan. It is now commonly deboned and cut into square fillets, but originally the whole eel was brocheted vertically and cooked that way, giving rise to the name “Hoyaki” due to the resemblance to the cattail both in form and color. Photo supplied.

Curious customers will be able to sample Edo-era cuisine at Mitsukoshi Nihombashi between September 20 and October 3, 2017. The Japanese food offered to shoppers are based on documents supplied by the National Institute of Japanese Literature.

“We have transcribed the calligraphy into modern type, and translated the Edo period Japanese into the modern idiom,” explained Kazuaki Yamamoto, who is a professor at the institute and has been involved in the digitization project. “Recipes have been taken from a great many cookbooks … Paper copies of many of these recipes will be included with the food served at Mitsukoshi.”

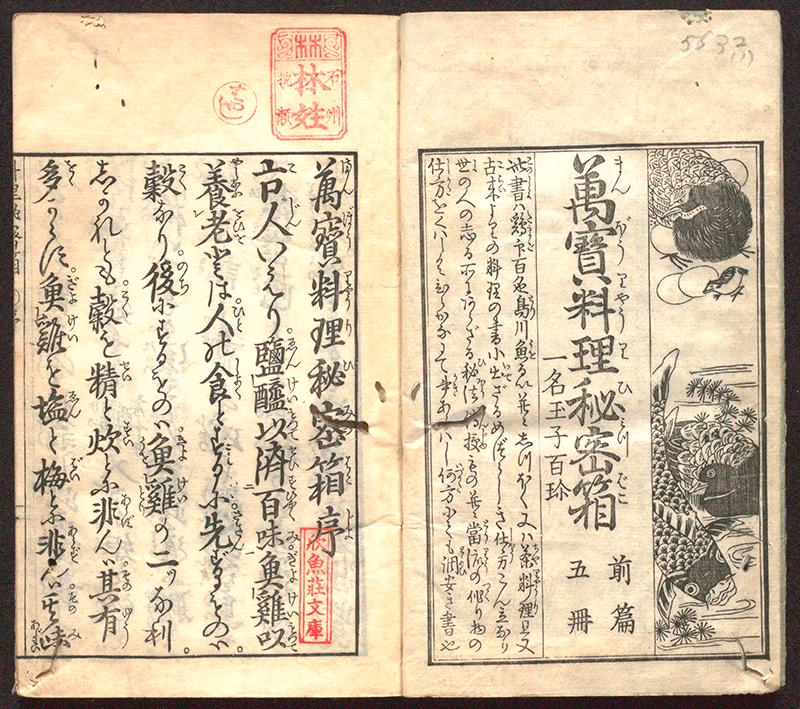

Pages from the old recipe book Manbō ryōri himitsubako, or Secret Treasure Chest of Ten-Thousand Recipes. Image licensed under the Creative Commons License 4.0 (CC-BY-SA 4.0 NIJL/CODH). Source: http://codh.rois.ac.jp/index.html.en

The Hallmarks of Edo Period Japanese Food

When Weekender asked Yamamoto to summarize the characteristics of Edo period cuisine, he said there were two salient features. “First, Edo period recipes use a very limited selection of seasonings, the most common of which are miso, soy sauce, vinegar, salt, sugar, alcohol, and dashi,” he told us. “Second, the main ingredients consist mainly of rice, fish, and various types of vegetables.”

Yamamoto said sometimes chicken was prepared, although only on special occasions or for people who were experiencing an illness, and beef and pork were generally not eaten. “It was not until the Meiji period – that is, the latter half of the 19th century – that Japanese people began including these sorts of meat in their diet.”

Yamamoto said Japanese food cookbooks compiled during the 17th century indicated that the teachings of Buddhism and the philosophy of the tea ceremony had some influence on the nature of Japanese cooking. Cookbooks begin to show a considerable increase in the variety of ingredients from around the second half of the 18th century, he said, driven by a rise in commerce and transportation.

“Most noteworthy, however, is a marked preference for strictly seasonal ingredients. In fact, cookbooks of this time were generally divided into four sections, one for each season,” Yamamoto said. Providing more food for thought, he added: “Incidentally, sushi has become quite popular nowadays. During the Edo period, sushi was referred to as narezushi; that is, naturally fermented fish on rice. What we today call sushi was known to Edo period people as hayazushi, literally fast sushi – what we might call a kind of fast food – and is rarely mentioned in Edo period cookbooks.”

Compared with the current style of sushi, the rice ball in the Edo period was at least 1.5 times larger. Townsfolk of Edo were so busy that they ate sushi at the counter standing in the street stalls. Six pieces of “Hayazushi” will be sold for ¥2,160 at Kuhashi, a retailer within Mitsukoshi Nihombashi. Photo supplied.

The event runs from September 20 to October 3 (10:30 to 19:30) at Nihombashi Mitsukoshi Main Store, 1-4-1 Nihombashimuromachi, Chuo-ku, Tokyo: http://mitsukoshi.mistore.jp/store/nihombashi/index.html

For more information on the National Institute of Japanese Literature-led project to digitize thousands of pre-modern books, see http://www.nijl.ac.jp/pages/cijproject/index_e.html

To flick through the pages of the 1785 cookbook Secret Treasure Chest of Ten-Thousand Recipes, go to http://kotenseki.nijl.ac.jp/biblio/100249426/viewer/1 or browse the web-friendly version of the recipes (in Japanese) at http://codh.rois.ac.jp/edo-cooking/

Main Image: Townfolk in Edo cooked tofu in various ways and they put 100 recipes into the book “Tofu Hyakuchin.” Kakuhiryu-zu is one of the recipes and it will be arranged with “Kikuka-ann,” the thick sauce with shredded chrysanthemum sprinkled. Kusatsutei, a retailer within Mitsukoshi Nihombashi, will serve deep fried tofu mixed with vegetables and minced fish for ¥324. Photo supplied.