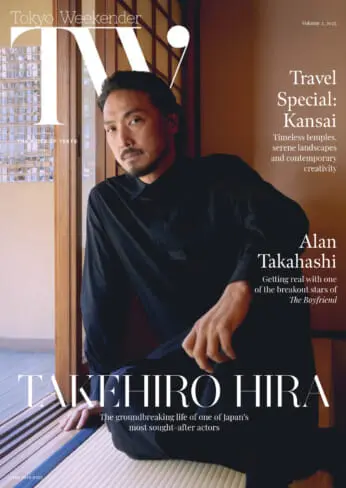

Japan is a giant in the world of cosmetics. In 2023, its cosmetics and personal care products market was ranked third largest after those of the US and China. That same year, Shiseido, the biggest beauty business in Japan, had ¥973 billion in sales. But Japan’s interest in beauty isn’t limited to recent years; the country has a long history of using makeup.

During the Edo period (1603–1867), makeup reflected a woman’s social position, class and age. The unique style constrained makeup to just three colors: red, white and black. Various ukiyo-e woodblock prints of that era, such as Utagawa Kunisada’s “The Dance Teacher” (signed “Kochoro Kunisada”) from the series “Contest of Present-day Beauties,” show us a glimpse of the daily routines and makeup culture of women from Japan’s past.

Dance Teacher (Odori shishô), from the series Contest of Present-day Beauties (Tôsei bijin awase), Utagawa Kunisada I, National Diet Library collection

Geisha also utilized these traditional colors: A white powder base called oshiroi applied to the face and red-lined eyes and lips helped them stand out in the candlelight when servicing their clientele.

Going back even further, makeup customs from the Heian period (794–1185) also expressed social standing, though they did so for both men and women. Aristocrats would paint their faces to display their noble status to the emperor. These practices were, in fact, the origins of geisha makeup.

Beni is a form of traditional Japanese makeup, a rouge made out of the red pigment of safflowers, known in Japanese as benihana. While most people outside of Japan associate the word “benihana” with the popular chain of teppanyaki restaurants, the flowers the word refers to were a valuable commodity during the Edo period, as they were raw material for dyes and cosmetics. The flowers, believed to be native to the Middle East and Egypt, arrived in Japan sometime around the mid-third century, after they were brought to China along the Silk Road.

To turn the flowers into a usable cosmetic, the red pigment was extracted and processed into a glaze-like product. The rouge, which could be used on the lips, cheeks and eyes, became a fixture of women’s daily grooming practices, and remained popular for geisha and kabuki actors. Beni culture prevailed until around the 19th century, at which point Western-style lipstick and blush became the new craze. But even though it’s no longer a feature of most women’s cosmetic kits, beni is still sold and used today.

For a historical behind-the-scenes look at one of Japan’s oldest cosmetic secrets and where you can experience it for yourself, read on.

What Is Beni?

Beni is made entirely out of natural ingredients, and according to Isehan-Honten, the last shop in Japan producing beni using traditional techniques, approximately 1,000 safflowers go into making just one beni container. This is because, out of the whole safflower, less than 1% of the petals contain the precious red pigment, making the extraction of beni an extremely time-consuming, highly skilled task.

Historically, the farming process consisted of plowing the fields and planting seeds in March. Once the flowers bloomed and were processed, farmers made benimochi — compact patties of dried and fermented flower petals — in preparation for shipping. The pigment would finally arrive in Kyoto, one of the biggest production areas for beni, around October.

During the processing stage, the pigment was refined through chemical reactions using a combination of lye, rice vinegar and plum vinegar. Lye was poured onto the benimochi and a beni-pressing machine squeezed the flower petals to extract a dark red liquid. The solution was poured into a basin to be soaked up by hemp bundles. The bundles were then dipped in lye again, wrapped in cloth and sent to be pressed through the machine again. These steps were repeated several times to increase the purity of the pigment. Finally, plum vinegar was added to the concentrated beni solution, which was sent for a final filtering through a cloth.

IsehanHonten. (2013, Jul 09). How To Use Komachi Beni [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PeI9vKFDuf0

The History of Beni

Since ancient times, Japanese people have associated the color red with the sun, fire, blood — and life itself. Beni’s vibrant red pigment was believed to protect people both physically and spiritually by stimulating blood circulation and by acting as a talisman to ward off evil. On a newborn’s first visit to a shrine, the baby would be marked with beni or red ink to protect them from evil spirits. During shichi-go-san celebrations when a child turns 3, 5 and 7 years old, a talisman bag and beni-choko were commonly prepared as gifts.

As discussed above, makeup in the Edo period was used to designate a woman’s status by making her social attributes visible and identifiable. Brides would blacken their teeth in a practice known as ohaguro just before they were married, and new mothers would shave their eyebrows after giving birth. These alterations to a woman’s appearance acted as an indicator of her shift within the social hierarchy. Women in the upper ranks of samurai families would paint on a new, thinner set of eyebrows after shaving off their natural ones.

For geisha, beni was used to line the eyes and lips. First-year maiko (apprentice geisha), were typically only allowed to apply beni to their bottom lip. More senior maiko and full-fledged geisha got to apply the lipstick to both lips, and the lips were painted smaller than they actually were to give a more youthful, cute and proportional appearance.

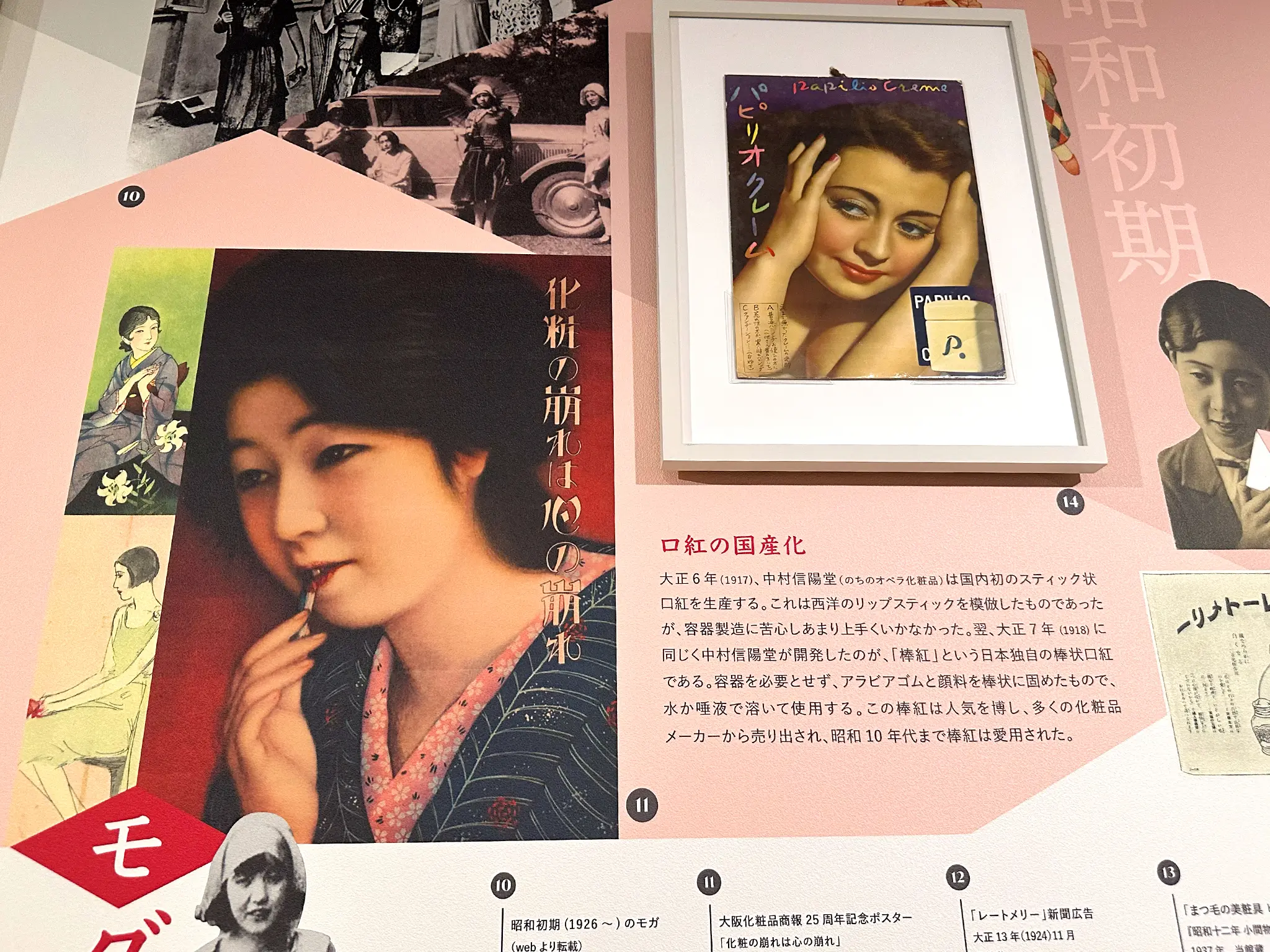

With the opening of Japan’s borders in the Meiji period (1868–1912), a new age of makeup arose as a result of international exchange and extensive Westernization. Japan’s makeup industry started to incorporate Western trends and products. Meanwhile, beauty standards began to stray from the traditional look after visiting foreigners firmly rejected customs like teeth blackening and eyebrow shaving, declaring them “barbaric.” Rutherford Alcock, the first British diplomat to live in Japan, described the practice thusly: “When they have renewed the black varnish to the teeth, plucked out the last hair from their eyebrows, the Japanese matrons may certainly claim unrivalled pre-eminence in artificial ugliness over all their sex.” In 1870, the practice of teeth blackening was banned by the Japanese government, and it gradually disappeared.

After such intense criticism, women began to focus on ways to maximize natural beauty. Oshiroi was replaced with skincare and powder while beni was replaced with blush and lipstick. It was also during this time that women started enjoying makeup not as a societal marker but simply as fashion and self-expression. By the end of the Taisho period (1912–1926) and into the early Showa period (1926–1989), “modern girls” were mimicking European and American trends and actresses they admired on the silver screen. One tenet that remained from ancient tradition, however, was the idea that makeup was part of self-grooming and an important part of maintaining appearances for social interactions.

Experiencing Beni Today

While today, Western-style cosmetics have largely taken over Japan’s cosmetics market, you can still experience traditional products like beni.

The Beni Museum, located in Tokyo’s Aoyama neighborhood and free to enter, offers guests a rare look at the craftsmanship and history of beni and Japanese cosmetics. It even has a hands-on zone where you can try applying beni yourself. And, as the museum has tablets that translate every display, even non-Japanese speakers can easily enjoy themselves. Isehan Honten, as the only remaining beni shop from the Edo period, has truly committed itself to preserving the craft and culture surrounding traditional Japanese beauty.

“Recently, thanks to the influence of TikTok and YouTube, many young people are coming here to try and buy beni,” says a member of the museum staff. “I’m really glad that the younger generation is getting to know the traditional Japanese beni.”

Should you visit, be sure to take the time to admire Isehan Honten’s beautiful ceramic beni-choko, which you’ll find in the museum shop. Beni, a staff member explains, isn’t just used by professionals; it’s also used by regular people. With prices ranging from ¥10,000 all the way to ¥80,000, the museum shop’s beni-choko make luxurious gifts for weddings and birthdays — not to mention souvenirs.

Beyond its exquisite presentation and historical depth, beni has additional merits: Because it’s stain-based rather than oil-based like modern lipstick, it doesn’t easily smear or transfer. “Beni leaves no marks on teacups, bowls, glasses or cups,” a member of staff explains. “So you can enjoy eating and drinking elegantly.”

For those on a tighter budget who still wish to participate in beni culture, Shiseido makes a very affordable version of beni, available for just ¥550. This type of lipstick was developed in the Taisho era and is still used by kabuki actors today. You’ll have to sacrifice the authentic and natural benihana pigment for synthetic color, but the lipstick still offers a fun experience of application with a brush.