Japanese horror has a long and fascinating history that may go back tens of thousands of years to precivilization animistic beliefs that eventually snuck their way into native Shinto myths like that of oni (demons, devils, ogres). Additionally, before it became a genre of art, J-horror was fueled by hair-raising and, sometimes, literally face-peeling real tales from Japanese history. And we’re not even mentioning the Edo period (1603–1867) tradition of the 100 Supernatural Tales parlor game that saw participants sit around 100 lanterns or candles and extinguish them one by one for each scary story told. The point is, Japanese horror is complex. You can’t just point to one thing and say, “This is where a lot of the modern stuff comes from.” You need at least three things, like these:

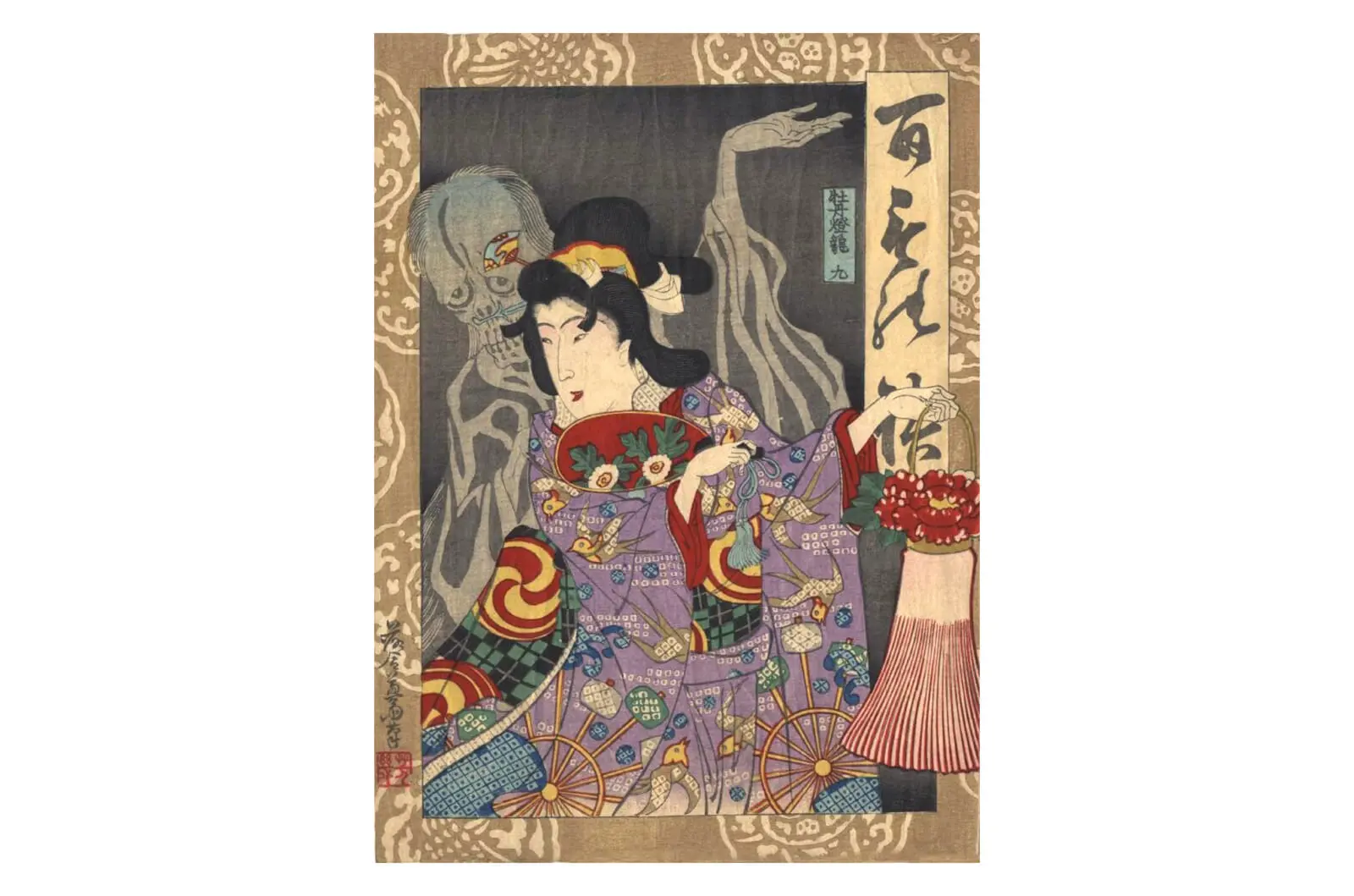

Botan Doro (The Peony Lantern)

The 17th-century Botan Doro starts on the first night of Obon, when the souls of the departed are said to return to Earth. It tells the story of one Ogiwara Shinnojo, who spots a beautiful woman being escorted through the streets by a servant carrying a lantern with a peony motif. He decides to chat her up, because nanpa has been a problem in Japan for far longer than we thought.

The woman introduces herself as Otsuyu and accepts the man’s invitation to his house, where they end up having sex. She leaves before sunrise but promises to return. Ogiwara and Otsuyu’s trysts continue for weeks until he starts neglecting his friends, job and all other obligations.

One day, a concerned neighbor peeks inside his house and sees Ogiwara in the embrace of a moving and talking skeleton. The next morning, he warns Ogiwara that his bone buddy is quite literally a bone buddy, urging him to go talk to a local monk, who shows the man Otsuyu’s grave with a weather-beaten peony lantern on it. The monk gives Ogiwara a talisman to protect him, and after that, Otsuyu’s visits stop completely.

Over time, though, Ogiwara starts missing Otsuyu. Trying to deal with the realization he might be a necrophiliac, he starts drinking and one night ends up near her grave. There he finds Otsuyu, as beautiful as ever, waiting for him. She takes him by the hand, and that’s the last anyone sees of Ogiwara. After a few days, the monk opens up Otsuyu’s grave and finds the dead Ogiwara hugging her skeleton.

An important detail of Botan Doro is the fact that Otsuyu’s grave was untended to, possibly making her apparition a muenbotoke, or the “unattached Buddha.” These were the ghosts of the forgotten, who spent their undeath fulfilling their most primal desires. This isn’t something they can control; it’s like an irresistible drive fueled by something more powerful than we could ever imagine, and it frequently appears in Japanese horror where forces of nature or the supernatural are often unstoppable.

In Western horror, “evil” can be fought and defeated. In Japanese horror, it can be avoided at best. We actually see this a lot in movies like Ring, where the ghostly Sadako cannot be beaten. Her curse can only be passed to another person. In the end, humans aren’t powerful enough to overcome the supernatural. That’s Botan Doro, and also the bulk of Japanese horror.

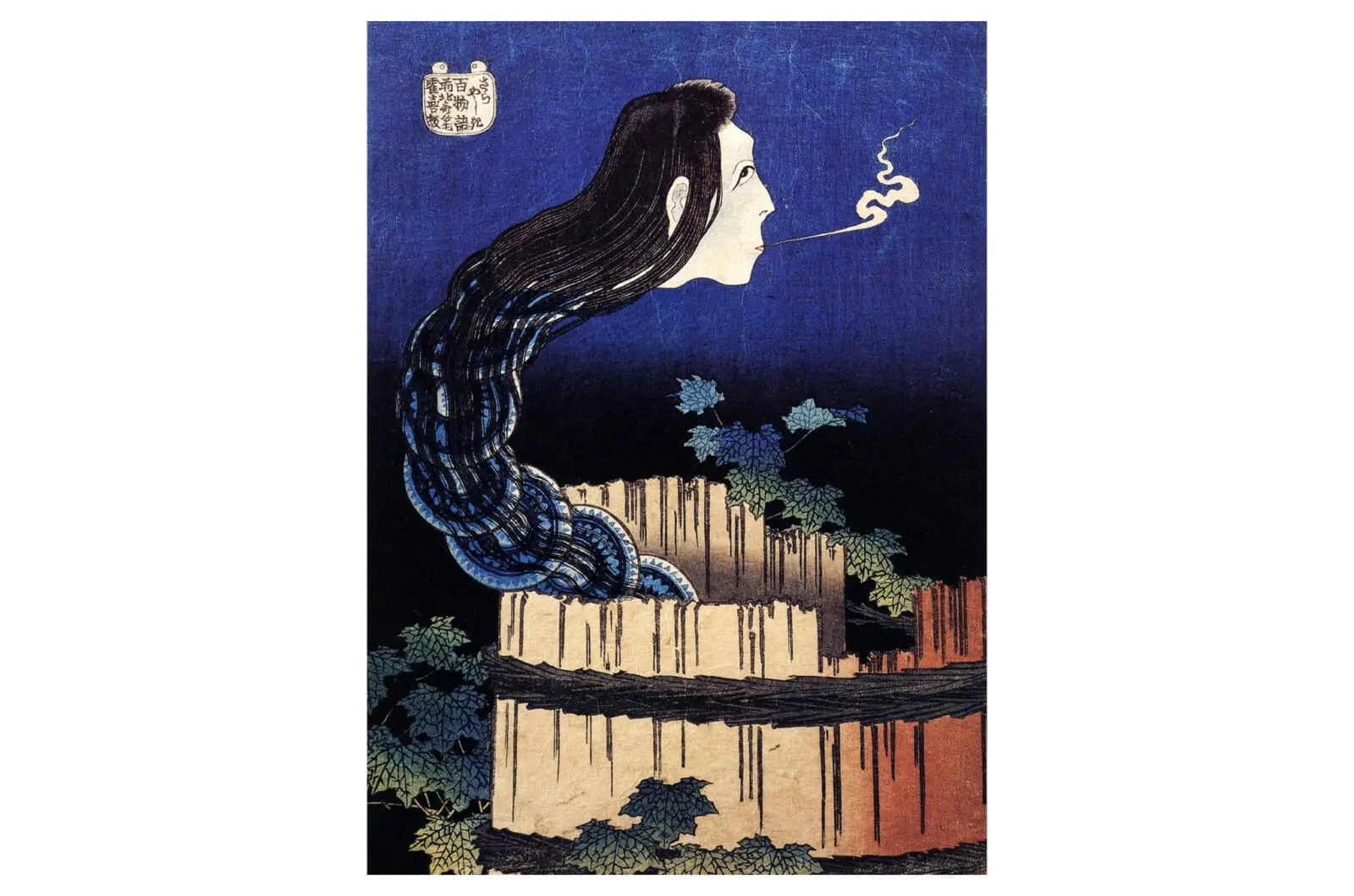

“The Mansion of the Plates” (1831), Hokusai

Bancho Sarayashiki (The Dish Manor)

Speaking of Ring, this is the story that had a big influence on it. According to the tale, there once was a poor girl named Okiku who found employment as a dishwasher at a lord’s mansion in Edo (modern-day Tokyo) or at Himeji Castle (in modern-day Hyogo Prefecture). The important detail is that the place had high-class stuff but low-class staff in the form of a retainer named Aoyama, who wanted to make the beautiful Okiku his mistress. She kept refusing him until Aoyama resorted to blackmail. He hid one of his master’s prized dishes and accused Okiku of stealing it. Panicking, she frantically counted the dishes in the 10-piece set, always coming up one short.

Aoyama then proposed that he would tell the lord that Okiku was innocent if she became his lover. But even facing possible death for her “crime,” Okiku refused Aoyama. He reacted poorly, having the girl beaten, tied up and repeatedly dunked in a well. After another rejected offer of life for sex, Aoyama killed Okiku and dropped her body in the well. But she soon returned, her ghost wandering the estate grounds, counting up from one and shrieking wildly in despair after getting to nine. It was said that those who heard her count all the way up to nine would die soon, essentially making Okiku a kind of Japanese banshee. Technically, though, she was an onryo.

Literally translating to “vengeful ghost,” onryo are one of the oldest malevolent supernatural forces in Japanese myths and legends, dating back to around the eighth century. Initially, most of them were male, but with time, the majority of onryo became female. Many theories have attempted to explain this change, from a perceived connection between women and the world of mysterious and powerful nature to trying to give women in death the power they lacked in life in Japan’s highly patriarchal society. Today, their appearance in the public consciousness has been greatly influenced by kabuki theater, where onryo often wear white clothes and have long, unkempt hair that obscures their face. Between this and Okiku being killed in a well, the connection between Bancho Sarayashiki and Ring could not be any clearer.

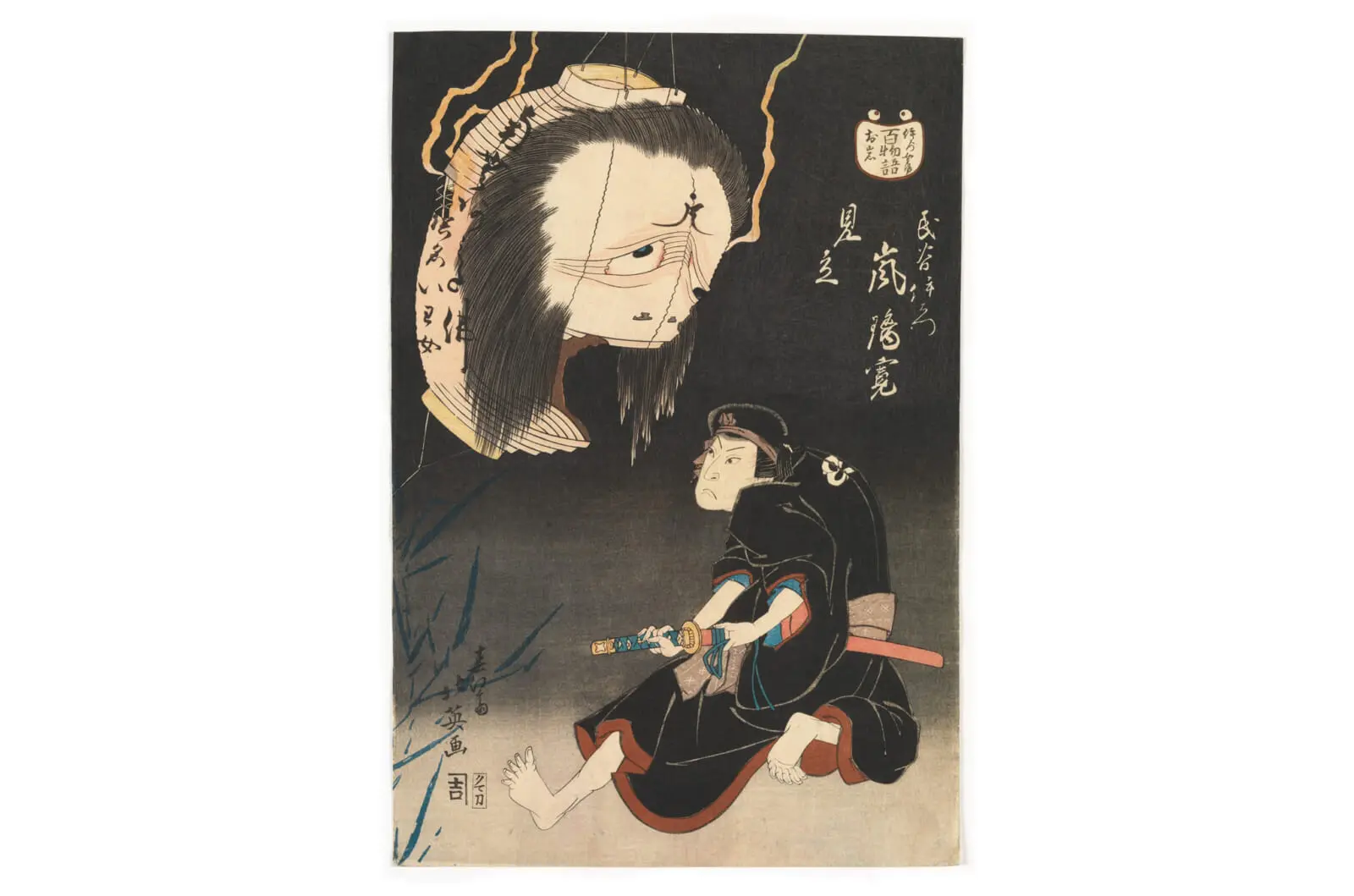

“The Ghost of Oiwa” (1831), Hokusai

Yotsuya Kaidan (The Ghost Story of Yotsuya)

Possibly the most famous Japanese ghost story of all time, Yotsuya Kaidan tells of the beautiful Oiwa, married to a ronin named Iemon — a man who makes Aoyama from Bancho Sarayashiki seem eligible for pope. Not only was Iemon an inconsiderate jerk, idler and gambler, he actually murdered Oiwa’s dad when she was contemplating leaving her husband. Blaming the death on a passing robber, Iemon won her back by swearing to avenge her father’s death. The search didn’t take up a lot of his day.

Iemon eventually befriended a rich doctor with a beautiful granddaughter who instantly fell for him because being a ronin was like the Edo-period equivalent of owning a motorcycle, apparently. The doctor promised Iemon a life of riches and leisure if only he got rid of Oiwa, so he prepared poison disguised as medicine for her because she was feeling ill due to recently having given birth. Over time, the poison hideously disfigured Oiwa, distressing her so much that she accidentally slashed her own throat and died while cursing Iemon. (We’re skipping a few details, but she realized Iemon’s betrayal shortly before her passing.) Her ex then killed the servant who brought him the news of her death because he was the worst.

Then the hauntings started. Iemon started seeing Oiwa’s disfigured face everywhere, and before he figured out it was an illusion, he killed his new wife and father-in-law thinking they were the ghosts of his wife and servant. Appearing to him in everyday objects such as lanterns, Oiwa kept hunting Iemon until he went mad.

A common depiction of the onryo Oiwa includes her droopy eyes, one looking up and the other down. That might be a reference to tenchigan (“the eyes of heaven and earth”) often found on Buddhist statues where they symbolize fury. We see similar disfigured eyes on Sadako in Ring, as Yotsuya Kaidan was also a big inspiration for the supernatural character. Meanwhile, Oiwa appearing in everyday objects could have partially inspired the idea behind House (1977), one of the greatest Japanese horror movies ever.

But even that’s not where the story’s horror legacy ends. Yotsuya Kaidan is a tale about the breakup of a family due to infidelity, which is also found in the Ju-On (The Grudge) series and plenty of other horror films where disturbing the traditional results in disturbing attacks from malicious supernatural forces. Japanese horror is, of course, more varied than “powerful nature,” “vengeful ghosts” or “the protection of tradition,” but those themes definitely make up the foundation of J-horror, and they all descend from the stories of the three O-girls.