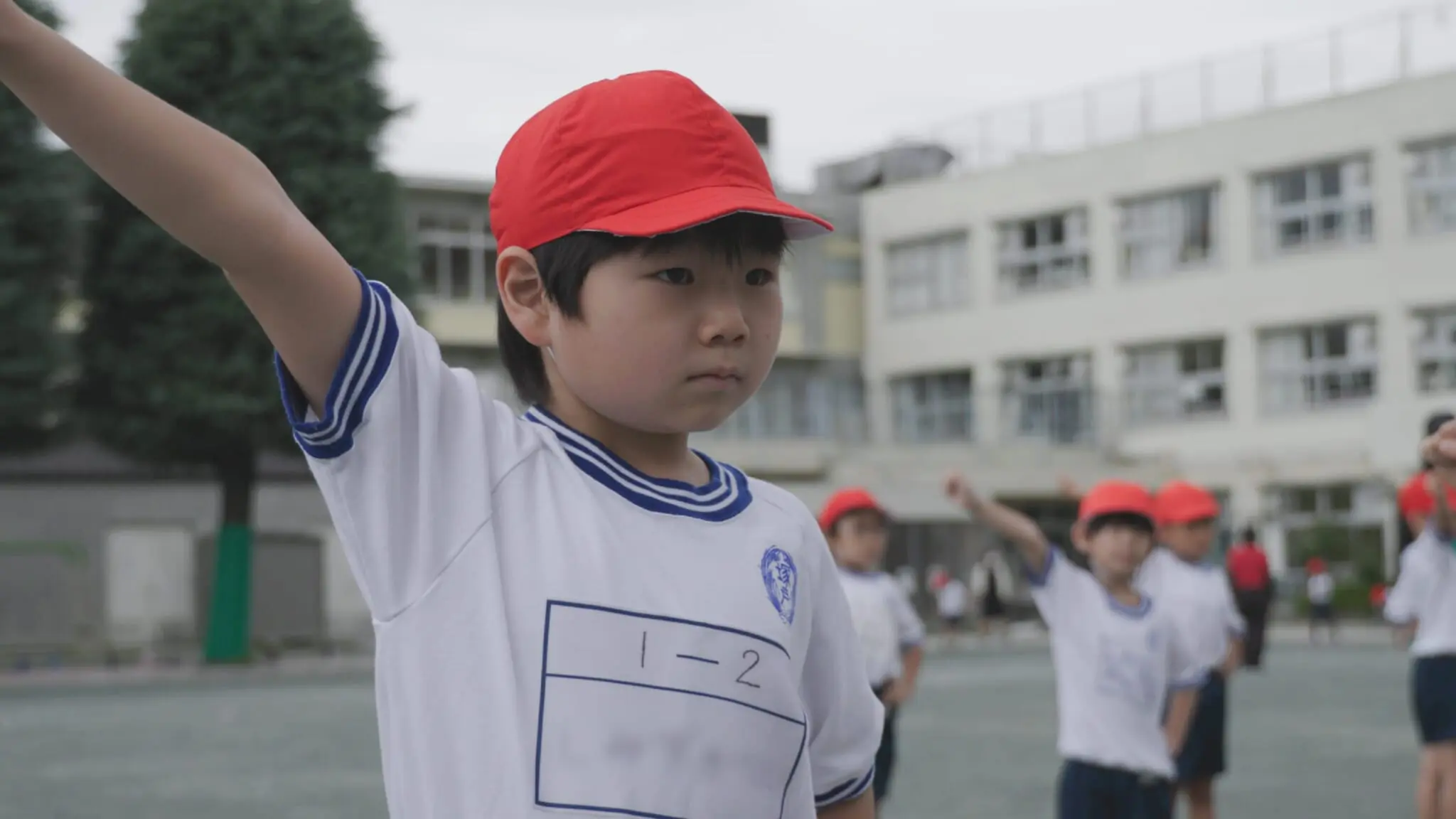

What makes someone Japanese? Ema Ryan Yamazaki’s newest documentary, The Making of a Japanese, hinges on this question. The 99-minute film starts with 6-year-old Yutaro neatly placing his shoes at the entrance of his home and holding his breath while carrying a tray of plates to the table. He’s practicing for his first day of Japanese elementary school, where he will be faced with challenges in and out of the classroom — including perfectly placing his shoes in his cubby. The film takes place over the course of an entire school year, starting with a whir of shiny new randoseru backpacks and tiny legs ushered to walk in a straight line under the anxious gaze of parents and faculty.

The Making of a Japanese carefully follows the intricacies of the Japanese public school system, with unprecedented access to the goings-on of daily life. “Our goal was to become part of the system,” Yamazaki explains. “We were so seamlessly there that the kids and teachers got to the point where they would behave [in their usual way], regardless if we were there.”

The film at once details the quotidian normalcy and strict intensity of Japanese elementary schools: the perfectly organized shoe boxes, an emphasis on responding with a perfectly clear “hai!” when called and keeping one’s mask on at all times (the documentary was filmed during the height of the coronavirus pandemic). Key players color the landscape of school life, including wild child Yutaro; Ayame, a go-getting little girl chosen to play the cymbals for a school-wide assembly; and Endo-sensei, the sixth grade teacher who cracks an egg on his head to make a point about “breaking out of one’s shell.”

One of the most impactful scenes of The Making of a Japanese takes place when Ayame makes a mistake while practicing her cymbals. The teacher admonishes her in front of her classmates, and Ayame is overcome by a flood of tears. For the final rehearsal, she grows scared to perform for fear of being yelled at again, but through the encouragement of her peers and teachers, she manages to perform perfectly.

“The strictest teachers — they were my teachers, and I feel like I was Ayame,” Yamazaki says. “I didn’t understand at the time, but 20 years later, it’s the foundation of my strength. It’s harder to be a teacher who’s stricter these days; it’s much easier to just be everyone’s friend. But what is education? I think a school needs all types of teachers, and I really want people to think about that balance of pushing and respecting students.”

Ema Yamazaki reflected in a classroom mirror in Tokyo, Japan.

Making of a Film Director

For Yamazaki, a half-Japanese, half-English documentary filmmaker who grew up in the suburbs of the Kansai region and attended Japanese public school until the age of 12, the Japanese school system had a major influence on her life: “I kind of feel like if you’ve experienced Japanese elementary school, you’re Japanese. Everything about myself I consider to be Japanese, I feel like I learned in those six years.”

Yamazaki’s biracial identity complicated her experience with the Japanese education system, as there were times she felt like an outsider in her own country. On one hand, she was a “very Japanese girl, with a very Japanese education, in the heart of the Japanese system.” On the other, she was “always the only person around that had a foreign parent. I distinctly remember that I thought being able to speak English was a bad thing about myself,” she recalls.

After graduating from elementary school, Yamazaki transferred to an international school with a less typically Japanese education style. Then, for college, she decided to move to New York in pursuit of her long-time dream of studying filmmaking. In the States, she experienced a bit of unexpected culture shock: She was praised for qualities in herself that she felt were just natural. “I would get constant compliments like, ‘You work so hard, you’re always on time, you’re such a good team player.’ And I would think, ‘I’m just Japanese.’”

As Yamazaki made her way through New York University’s Tisch program, her passions became clear to her. “I quickly realized all I wanted to do was documentary filmmaking, even though most of my school actually [specialized in] fiction films,” she says. “I realized that I don’t have any extraordinary stories in my head that I want to tell. It’s just about using myself as a filtered perspective to share something that I find interesting.”

After graduating, she worked in the film industry as an editor, but she struggled with the lack of creative freedom. “I stayed in New York and edited documentaries that were on things like CNN and HBO. But when you’re an editor, you don’t have control of the stories you’re telling, because it’s someone else’s idea. And as much as I enjoyed learning about these American stories, I was always playing catch-up. I wanted to see what it feels like to have control over [the narrative], and tell the stories that I want to tell.”

Finding a Narrative

When Yamazaki made the leap to become a film director, her first feature film was, surprisingly, not about Japan at all. “I made a documentary about the authors of Curious George,” she says. “Growing up with him, I thought he was a Japanese monkey. I was like, ‘Oh, you guys had him too?’ It was one of the few universal things that I had in common with some of my friends.”

Yamazaki was immediately drawn in when she came across the story. “It turns out that Curious George‘s authors were husband and wife. They were German Jews who fled on bicycles, carrying the first unpublished Curious George book with them. The love story and the way that they told their own story … the whole thing was so amazing. I assumed there was already a movie about it, but when I realized there was no movie, I was like, wow. I tried to keep the project a secret because I was just like, ‘Spielberg’s going to do this.’”

After completing this first passion project, Yamazaki was eager to tell a story through which she could share her own perspective about Japan. “I was so tired of everything being about sushi or samurais or ninjas; it was such a limited view of Japan,” she says.

Living abroad had given her a new appreciation for her home country and drawn her attention to parts of Japanese culture she’d previously taken for granted. “In the nine years I was in New York, I had grown to see Japan in a totally different light. When you get to New York and you don’t know when the next subway is showing up, and there’s rats everywhere and it’s really dirty, you’re just like, ‘What? It’s not a given that our trains show up on time?’”

Yamazaki wanted a way to document the country she grew up in — and not just the surface-level “what” Japan is like, but a deeper “how.” For her second film, Koshien: Japan’s Field of Dreams, she dug into a distinctly Japanese topic: the hyper-competitive world of high school baseball. This was her first time tackling the themes that reemerged in The Making of a Japanese; the documentary deftly investigated questions of uniformity vs. individualism and showed students both thriving and struggling in the rigid system.

A key scene comes toward the end of the film, when one of the coaches tells the students they no longer need to shave their heads to be part of the team. Though this may seem insignificant to an outsider, it actually represents a huge cultural shift. High school baseball in Japan is famous for its intense and vigorous training, and mandatory buzz cuts were the norm for decades, serving as a symbol of each player’s dedication to the team. “I knew I was witnessing a distinct moment of change,” says Yamazaki. Indeed, in the six years since that was filmed, the rate of shaved heads among Japanese high school baseball players dropped from 90% to 30%.

At the end of the day, Yamazaki isn’t trying to advance a specific viewpoint or grand theory of Japanese society. She wants to show her subjects as they are, without judgment or presumption; the result is always complex and often incredibly moving. “I have theories about the system or whatever, but I like to tell human stories about human challenges and human triumphs and human struggles,” she explains. “The Making of a Japanese is ultimately about how hard it is to be a first grader sometimes, or how hard it is to be a teacher, which is an impossible profession. I’m just trying to capture it in a way that more people can empathize with.”

Through this empathy, she wants to get viewers to truly engage with complicated problems — to think about them as they play out in individual human lives, rather than criticizing systems in broad strokes. “The million-dollar question is, ‘What should Japan keep about its traditional ways, and what should change be influenced by?’ and I don’t have the answers,” Yamazaki says. “What I try to do in The Making of a Japanese, and all my films, is to get people to think about it. You can’t have our trains running on time and also have a super individualistic, I-do-what-I-want society, so where do we want to land?”

The Making of a Japanese will be released in Japanese theaters on December 13, 2024. In select theaters including Cine Switch Ginza, English subtitles will be available via UDCast tablets. Visit the film’s official website for more information.