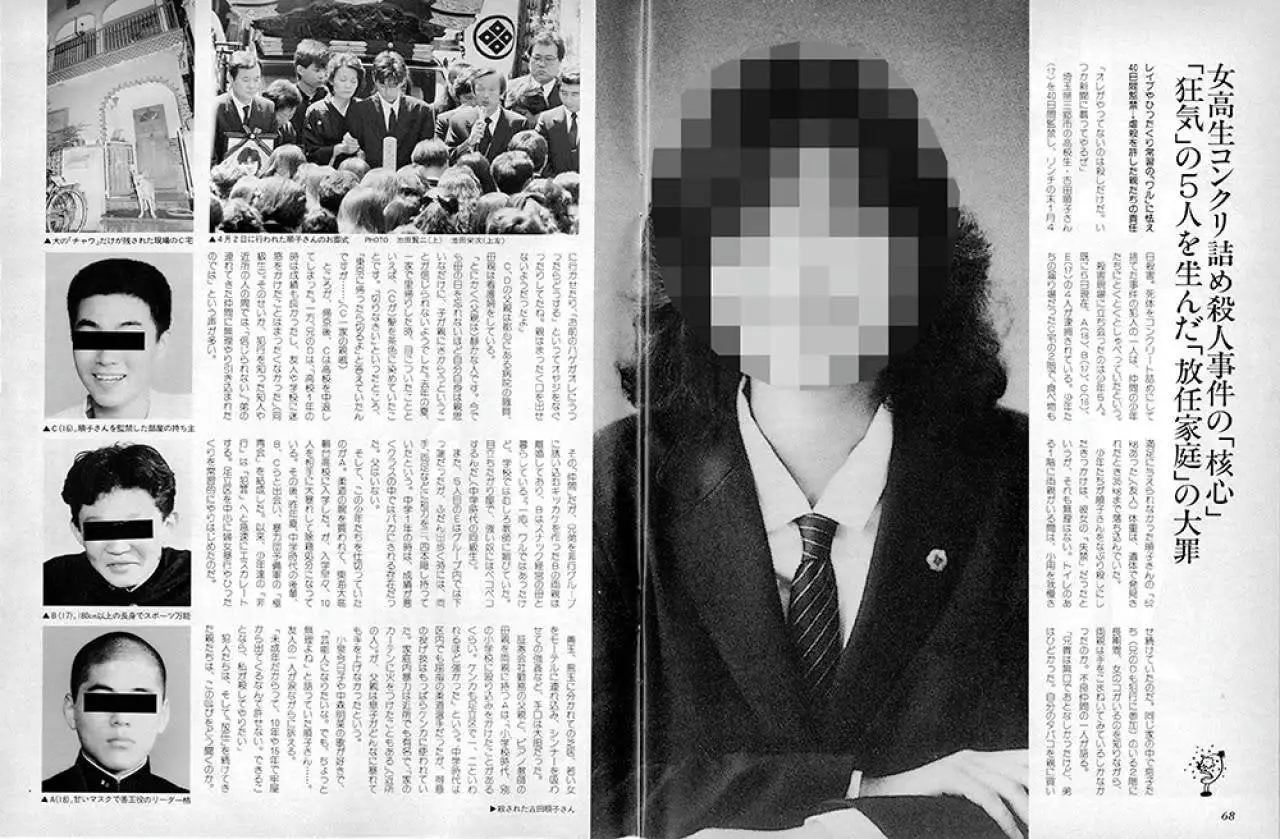

In 1989, a vacant lot in Tokyo’s Koto ward bore witness to the horrific culmination of what is still regarded as one of Japan’s most heinous crimes: the murder of Junko Furuta, known as the Concrete-Encased High School Girl Murder Case in Japan. Over 41 days, 17-year-old high school student Furuta was abducted, subjected to unimaginable abuse, repeatedly raped and ultimately murdered. Her body was encased in concrete and discarded by the perpetrators, who were all teenage boys aged 16 to 18 at the time.

Over three decades later, on January 6 of this year, the case resurfaced on Japanese social media after a Hokkaido Broadcasting Channel report detailed the perpetrators’ lives post-crime. The reactions on X were filled with unrelenting fury:

“The co-conspirator in the murder died a pathetic death, but for someone who did such horrific things, they deserved far worse.”

“A ‘tragic death’? Junko’s death was infinitely worse — don’t dare spin sympathy for these monsters.”

The Crime and Its Perpetrators

The four central perpetrators were:

- Hiroshi Miyano (18) was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

- Jo Ogura (17) received a sentence of five to 10 years.

- Shinji Minato (16) was sentenced to five to nine years in prison.

- Yasushi Watanabe (17) was handed down a sentence of five to seven years.

Hiroshi Miyano: A Continued Descent into Crime

The ringleader, Miyano has remained elusive, avoiding public and media scrutiny. Reports surfaced in 2013 of his arrest for orchestrating a phone scam targeting the elderly.

Jo Ogura: Isolation, Paranoia and a Lonely Death

Ogura was released in 1999 and initially attempted to rebuild his life. He worked in the IT sector and married a Chinese woman in 2000. However, his mental state deteriorated, plagued by paranoia and feelings of persecution.

Psychiatrist Susumu Oda told the Hokkaido Broadcasting Channel in a 2005 interview, “He believed his coworkers were gossiping about his criminal past. This paranoia, formed during his incarceration, directly influenced his behavior post-release. His delusional tendencies reflected symptoms of paranoid personality disorder exacerbated by the prison environment.”

In 2004, Ogura was arrested again for threatening and assaulting an acquaintance over a perceived romantic rivalry. He was sentenced to four more years in prison. After his second release in 2009, he withdrew from society, relying on welfare and isolating himself in a small apartment.

In July 2022, Ogura was found dead in his bathroom, likely the result of an accidental fall. His mother discovered his body, with his head trapped between the toilet tank and bowl. He was 51.

Shinji Minato: Recidivism

Minato, whose home served as the site of Furuta’s captivity, lived a tumultuous life post-release. In 2018, he was arrested for assaulting a man with a baton and attempting to stab him over a parking dispute.

Yasushi Watanabe: Years of Isolation

Watanabe, who acted as a guard during the crime, spent years in isolation after his release in 1996, living with his mother in a locked room. His health deteriorated due to a degenerative brain condition, which his family could not afford to treat. He died in May 2021 at the age of 49.

Starting Over with Families

Two others, both 16 at the time, participated in the sexual assaults of Junko Furuta but not the murder. They were sent to a juvenile detention center. After their releases, both got married and had children. They claim to have disclosed their involvement in the case to their spouses.

Systemic Failures and the Challenges of Rehabilitation

The lives of the perpetrators lay bare the systemic failures of Japan’s justice system. Out of the six offenders, at least three reoffended — one with attempted murder — while another died in isolation, trapped in a life of social and mental collapse. Japan’s criminal justice system in the 1980s and 1990s focused primarily on punishment, providing little to no support for rehabilitation or reintegration.

According to Professor Chie Morihisa of Ritsumeikan University, “Prisons at the time prioritized punishment. Offenders rarely had opportunities to reflect on their lives or address the circumstances that led to their crimes. Without meaningful support, recidivism was almost inevitable.”

Since then, reforms such as the 2016 Act for the Prevention of Recidivism have introduced community-based reintegration programs focusing on housing, employment, and healthcare. Additionally, Japan’s 2025 overhaul of its penal system, replacing traditional prison sentences with custodial sentences, aims to incorporate therapeutic techniques like open dialogue, which encourages offenders to reflect on their lives and relationships.

Lessons from a Tragedy

The murder of Junko Furuta isn’t just a story of cruelty but a haunting reminder of the justice system’s inability to reckon with such extreme crimes. As the public’s rage continues to burn, it raises uncomfortable questions: What is justice in the face of such atrocities? Can rehabilitation coexist with justice? And can a society truly claim to honor its victims if it does nothing to address the conditions that give rise to such crimes?

The offenders of this case should never be forgotten, nor should they be forgiven. The case will forever live on in Japan’s collective consciousness — a reminder of the darkest corners of human cruelty and the need for systemic change to address both the causes and consequences of crime.