The Karate Kid (1984) — starring the sadly late Pat Morita as Mr. Miyagi (by now a pop-culture shorthand for “wise martial arts instructor”) — is said to have popularized karate in the US. Weird, then, that the movie was released in Japan under the nondescript title Best Kid. In any case, the franchise’s latest sequel, the Netflix series Cobra Kai, brought back the original cast of the movie and reignited the world’s interest in Japan’s famous martial art. The final episodes of Cobra Kai premiered on February 13, ending a gripping story that began in 2018. In honor of this seven-year journey, let’s go back in time and talk a little about the origin of karate.

COBRA KAI | Netflix Media Center

Linguistic Nationalism

The translation of the word “karate” as “empty hand” is a fairly recent invention, dating back to the early 20th century. In 1936, a group of karate masters met in Okinawa and decided to change the characters that “karate” was written with. By then, many dojo were already using the “empty” character for “kara” (incidentally, this is the same “kara” as in “karaoke,” which means “empty orchestra”), but the 1936 meeting made it official. Before then, karate’s “kara” was written with the character for the Tang dynasty, which has become synonymous with “China.” The martial art’s original name thus means “Chinese hand,” alluding to its supposed country of origin.

The 1936 replacement of the characters wasn’t an act of pure nationalism (though, let’s be honest, it was probably a factor). The main reason for the switch was to better align the name “karate” with the art’s philosophy and the Japanese character that it had acquired over the years. Incidentally, the master who personally preferred “Chinese hand” and was cautious about rushing into a name change was one Chojun Miyagi.

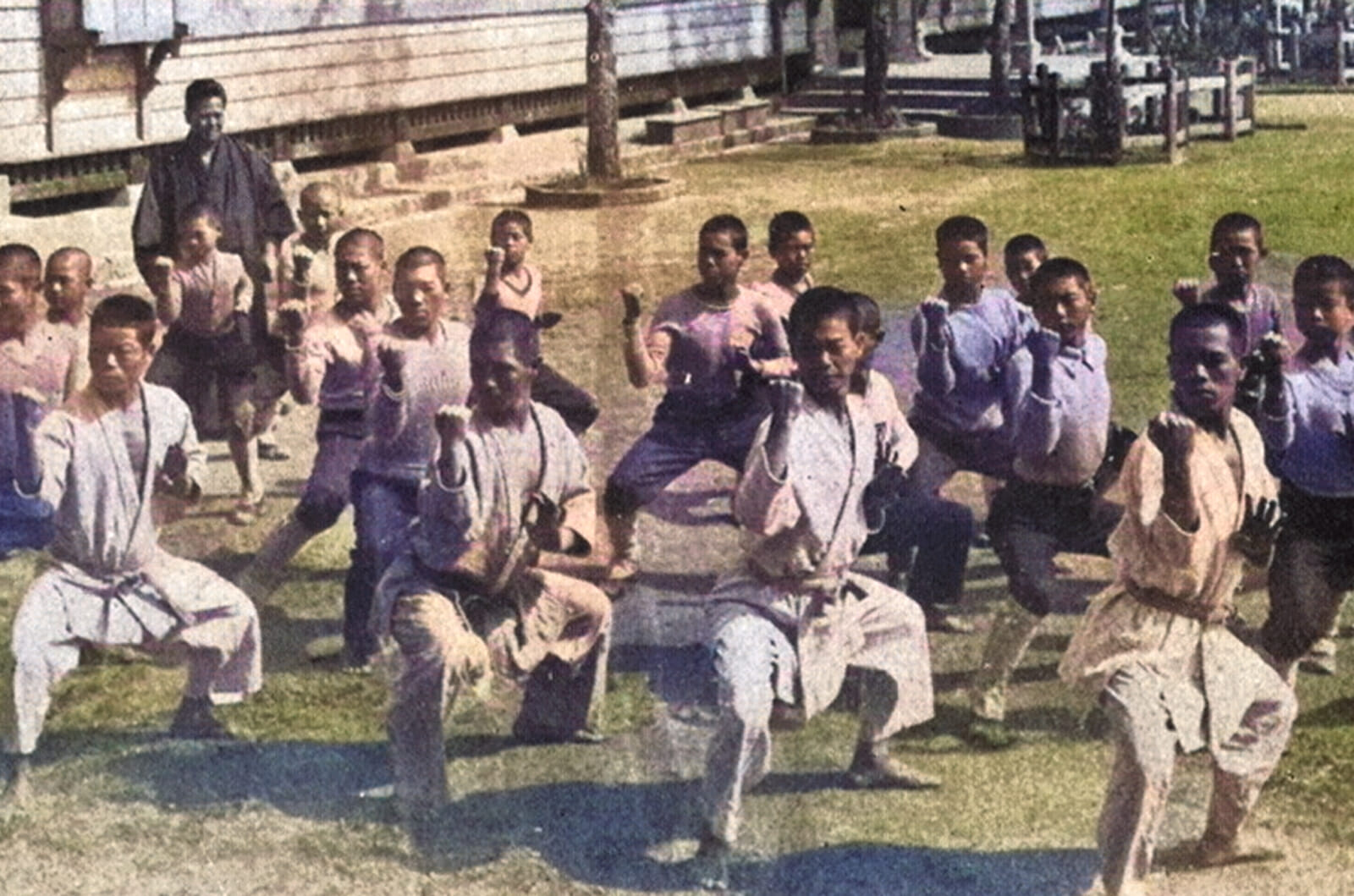

Okinawan Karate Training

Okinawan Dances, Songs and Chinese Kung Fu

While the seeds of karate may have come from China, they were cultivated in the soil of the Ryukyu Kingdom (modern-day Okinawa). Now part of Japan, it was originally an independent realm in the Chinese sphere of influence. Through contact with the Asian mainland, the people of Ryukyu learned of and took up kung fu.

The popular theory goes that Ryukyuans took Chinese kung fu and fused it with their native ti (aka tii, te or tee) martial art, meaning “hand,” thus creating the “Chinese hand” that would later be reinvented by Japanese martial artists like Gichin Funakoshi to eventually become the “empty hand.”

Not everyone agrees with this theory, though. In a 2023 interview, Kunio Uehara, the head of the secretariat of the Okinawa Dento Karatedo Shinkokai, questioned just how much China actually influenced karate. Rather than “fusion,” he prefers the term “inclusion,” suggesting that karate is mostly a Ryukyuan invention with some mainland influences. According to Uehara, if the martial art taught by Mr. Miyagi is a “mix” of something, it’s the original ti and other parts of Ryukyuan culture.

Uehara claims that the Ryukyuan courtship ritual of moashibi could have had an impact on karate. It involved innovative and spirited dances accompanied by music and songs, and Uehara sees similarities between moashibi and karate moves, making the latter spiritually close to the likes of capoeira. His other evidence is the popularity of the phrase “taeshinobinasai” — meaning “endure” or “be patient” — in traditional Ryukyu songs that would’ve been part of moashibi. Uehara asserts a link between it and karate’s “no first strike” principle. (Interestingly, the first rule of Cobra Kai-style karate is “strike first.”)

That’s, of course, just one theory, and the actual ratio of Chinese and Ryukyuan influences on karate will remain a hot topic of debate for the foreseeable future. One thing is certain, though.

Karate Was Not Invented by Peasants

The latest research makes one thing clear: Ryukyuan farmers did not invent karate. The popular, romanticized story says that after the invasion of Ryukyu by the Satsuma clan in 1609 (which is related to the story of the first and only Chinese samurai in history), the people of the southern islands were forbidden to carry weapons, so they practiced hand-to-hand combat to battle samurai and ninjas in guerilla attacks.

It’s a great underdog story, the spirit of which lives on in The Karate Kid and Cobra Kai, but there’s no evidence for it. In reality, ti and other martial arts were the pastimes of fief holders and other privileged people. We know this because the Ryukyu Kingdom had a strict social class system, and only groups like pechin (the gentry) and royalty are noted as practicing martial arts. The peasants were too busy tending fields so they wouldn’t starve to death. Some have suggested that the myth of the warrior peasant arose from low-level Ryukyuan aristocracy becoming destitute after the fall of the Ryukyu Kingdom while still holding on to the old customs like martial arts.

As for Satsuma’s ban on weapons, yes, that did occur — but it wasn’t widely enforced. Researchers of karate history like Tetsuhiro Hokama or Kohaku Iwai point to records showing that even after the invasion, the rich and powerful (aka the practitioners of early karate) held spear, sword and bow practices out in the open. As for peasants, most didn’t have weapons to begin with, especially as their own King Sho Shin (ruled 1477–1526) had issued a similar ban.

It’s true that an invasion of Japanese “foreigners” could have motivated commoners to develop a weaponless fighting system. But if they did, they never used it, as there are no mentions of Ryukyuan peasants organizing and attacking Satsuma samurai AFTER the invasion (though apparently they did defend their homes during the initial attack.) So, either peasants didn’t invent karate, or they did but were too scared to use it in practice. Given the documented cases of martial arts being the hobby of the upper classes, and to avoid calling Ryukyuan peasants “cowards,” let’s go with the former.