Kisho Kurokawa is redesigning Asia’s wealthiest cities

by Laura Fumiko Keeh

The father of the Metabolism movement in architecture, Kisho Kurokawa brings decades worth of experience to reconstructing Asia. For almost 50 years, Kurokawa has led the world in creating architecture and design conducive to interactive, ecological environments. His philosophy may be a reaction to the Congres Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) movement, a philosophy of architecture that dictated functionality over community. “When I was still in graduate school, the CIAM movement ended. It made me wonder what the next step in architecture should be,” says Kurokawa. He then formulated the basis of the Metabolism movement. “A half century later, I think my prediction was right,” he says.

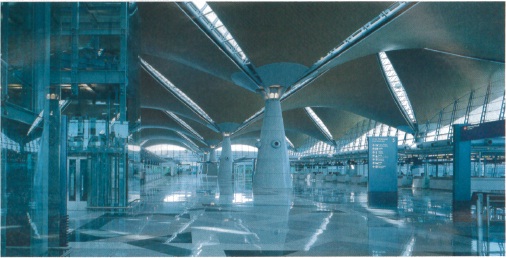

Kurokawa is currently designing Kuala Lumpur International Airport, the construction of which is a continuation of the building boom the Malaysian capital had in the late 90s. The new international airport follows in the footsteps of the twin Petronas Towers, the world’s tallest buildings when they were constructed in 1998 (currently they rank as the world’s second tallest behind the Taipei 101 in Taipei). The Petronas Towers are modern skyscrapers with strong Islamic designs.

Similarly, the airport, which is scheduled for completion in 2030, has very strong Islamic influences. “A high-tech design is natural for a modern airport,” says Kurokawa. But this does not reflect his philosophy of symbiosis. Malaysia’s prime minister Abdulla Ahmad Badawi requested that the airport reflect the Islamic culture of the country. Kurokawa explains that “through the use of hyperbolic geometric shapes,” the architecture effectively reflects Islamic aesthetics. “The prime minister is happy with the design,” says Kurokawa with a smile.

Another example of symbiosis currently in the pipeline for Kurokawa is Fusionopolis, a ‘city within a city’ in Singapore. Fusionopolis hopes to be a government-constructed ‘Bohemia,’ where creative go-getters in the business and technology fields will inspire each other in an artistic, free-spirited setting. The ultimate goal of Fusionopolis is to create independent-minded entrepreneurs and business leaders, who will then contribute to the overall economy.

Construction began in 2003, and should be completed after 2010. Kurokawa responded to the challenge of creating a nexus of creativity by designing Fusionopolis as three inter-connected high-rise buildings. It will be a “city in itself,” explains Kurokawa. “The roof is a park, and a preschool, then below is housing, offices, and shops. It’s a three-dimensional city. Not a horizontal city.”

When planning and constructing Fusionopolis, Kurokawa had to bear in mind that in Singapore, sunlight is considered harmful. Kurokawa was inspired to “make lots of shadows,” leading to the tight spacing of the three buildings.

Detractors are pessimistic as to whether a pre-fabricated city can really inspire organic creativity. However, Kurokawa excels in designing communities. His philosophy of symbiosis is not limited to the buildings he designs, but extends to creating whole environments.

Other large-scale projects with this theme include the re-designing of Zhengzhou, a city by the Yellow River in the central plateau area of China. The new city will have its ‘center’ constructed in the rim of the city, with high-rise buildings surrounding the actual center in two rings. The actual center will be flat, with buildings restricted to the equivalent of four to five stories. Kurokawa also made the existing canals a priority, saying he aims to “construct lakes and canals for symbiosis between car, pedestrian, boat, monorail, and bicycle.”

Kurokawa is also designing a new capital and airport for Kazakhstan, infusing a round design reminiscent of the Slavic onion domes into the design of the airport. Kurokawa’s designs elicit, rather than impose upon the environment, making him the architect of choice for the Asian business centers of the future.

This article is based on a presentation given by Kisho Kurokawa on Oct. 25, 2005, organized by the American Chamber of Commerce in Japan.

The mission of the American Chamber of Commerce in Japan (ACCJ) is to further the development of commerce between the United States of America and Japan, promote the interests of U.S. companies and members, and improve the international business environment in Japan. Established in 1948 by representatives of 40 American firms, the ACCJ has grown into one of the most influential business organizations in Japan, with more than 3,000 individual members representing more than forty countries and 1,300 companies. For information on ACCJ membership and upcoming events, see www.accj.or.jp.