Canadian shutterbug offers geisha guidance

by Tim Hornyak

Long-time Kyoto resident Peter Macintosh is one of the few foreigners to experience the geisha world from the inside. Tim Hornyak ventured into the “flower towns” of Kyoto to take one of his tours and find out how he got involved in one of Japan’s disappearing arts.

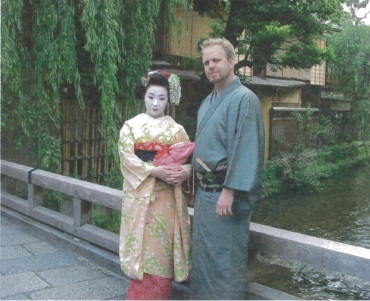

The empty evening lanes of Kyoto’s Miyagawa-cho echo with the jingle of bells in okobo clogs worn by a maiko tripping along to her next appointment. It’s a sight foreigners in Japan are sometimes lucky enough to catch while touring the ancient capital, but chatting up the white-powdered girl like an old friend is Canadian Peter Macintosh, an habitue of the secret “flower and willow world” of geisha.

The 33-year-old native of Halifax, Nova Scotia, has had the rare experience of living among Kyoto geisha circles for more than 10 years as a student of the arts, photographer and cultural guide. He has been featured in National Geographic‘s “Taboo” documentary series as a stalwart patron of the declining art of geisha and offers foreigners introductions to the entertainers known for centuries for their singing, dancing and conversation skills and so synonymous with the Japan of old.

On a recent evening, Macintosh accompanied me to the newly established Shin-kiro restaurant, a former teahouse near Kyoto’s Minami-za kabuki theater, and told me how his initiation into the demimonde of the hanamachi (“flower towns” where geisha work) simply “hinged on fate” after he came to Japan in 1993.

“I had been collecting geisha name cards after attending a geisha show in Kyoto, and then one night I went to a disco where a friend was deejaying,” he recalls. “Then this maiko-san enters in full regalia.”

Macintosh was struck by her dazzling entrance and tried to ask for her card.

“She was with this big mafia-type guy who just turned to me and said, ‘She’s a maiko — let’s go!’ And we went out drinking together.”

The encounter changed Macintosh’s life as it opened doors to other people in geisha society. Soon he was studying geisha and their arts, taking up ko-uta singing as well as photography. His teacher was a former geisha herself and gave him lessons in a Kyoto teahouse.

Macintosh even made his own debut on the geisha scene, performing in a music recital at Gion Corner Theater one September in front of leading members of the community. He still remembers how he got the shakes.

“I’m some whitey there in a kimono and the curtain goes up – and then a fly attacked me!” he laughs, adding he managed to remember the words and rhythm of his ko-uta, a short, highly allusive song form usually performed by geisha and accompanied by samisen.

A one-time pro soccer player, Macintosh immersed himself in traditional dance, calligraphy, sumie and flower arrangement while supporting himself by teaching English at a high school. The artistic training refined his photographer’s eye, and his connections allowed him to slowly become more intimate with local geisha and even to take pictures of them.

“I don’t think there’s anyone who’s put 10 years into it” among non-Japanese, he says while sipping sake at Shin-kilo, a stylish, youthful restaurant in Miyagawa-cho with a bar downstairs and tatami rooms upstairs. He says Arthur Golden only spent a brief time in Kyoto before his international hit novel Memoirs of a Geisha spawned a defamation lawsuit by Mineko Iwasaki, the former geisha on whose life it was based.

Macintosh himself married a woman who studied the entertainment arts of the tayu, the highest rank of Japan’s traditional courtesans who preceded geisha and were skilled in playing the kokyu, a Chinese stringed instrument that looks like a small samisen and is rarely seen today.

In fact, the first geisha were male entertainers, Macintosh explains, and were trained in song and dance. They emerged in the middle of the Edo Period (1600-1868) and were also called “hokan!’ The first women to enter the scene in 1751 were called “onna geisha” (female people of the arts). They gradually took it over, and by 1700 the profession was associated with government-licensed pleasure quarters such as Yoshiwara in Edo (Tokyo).

This was one reason that geisha have long been confused with prostitutes, especially by Western men visiting Japan, Macintosh notes while tucking into some eggplant tempura and sesame tofu. The misconception was compounded during the postwar U.S. Occupation of Japan as troops frequented Japan’s brothels.

“Actually, the geisha system aims at allowing women to achieve independence,” Iwasaki was quoted as saying by Reuters when she launched her lawsuit in 2001, alleging Golden broke a promise to keep her identity secret. “We are artists. We dance and perform music — this is how we earn our living. It is not about sex.”

Despite the controversy surrounding Golden’s novel, long-delayed plans to bring it to the silver screen apparently are finally being implemented. Macintosh recently guided Rob Marshall, the award-winning director of 2002’s “Chicago,” around Kyoto as part of location-hunting for the film. Auditions were also to be held in Tokyo for a Japanese actress to play the part of the story’s main character, the geisha Sayuri.

Macintosh estimates the number of geisha in Japan has plunged from 80,000 in the 1930s to about only 1,000 today, with some 250 in Kyoto, the center of the profession. One reason for the decline of geisha is the popularity in Japan of hostesses in Western-style clubs. Although geisha can continue working into old age due to focus on artistic and conversational skills, these days geisha are in the profession for a shorter time, Macintosh notes, adding there are no maiko, or apprentice geisha, in Tokyo.

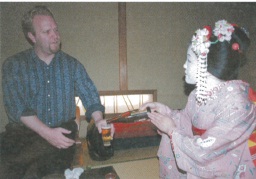

It is at this point that the tatami room grows silent and our guest arrives. The maiko Harukyo floats in like a little bird and bows before us, nearly touching her forehead to the mats. Beneath her ornamented coiffure and white face is a wave of pink kimono adorned with turquoise fans and lined with white and red. She’s all of 16 years old.

“Maiko” means “dancing girl,” and after exchanging polite greetings and a few giggles with us, Harukyo gives us a traditional dance expressing the seasons of Kyoto. The accompanying samisen music is on tape, but the performance is captivating.

Harukyo is originally from Chiba Prefecture, east of Tokyo, but has mastered the Kyoto dialect. Pouring sake, she chats about how she only gets a few days off a month from her entertainment appointments and studies and must complete five years of training in the arts before she becomes a full-fledged geisha.

She’s happy to answer questions about the geisha world, and Macintosh helps out with explanations when obscure nomenclature pops into the conversation. Before long, our time with Harukyo is up, and we are accompanying her back to her nearby okiya, or geisha house, where we bid her goodnight.

For foreigners who have lived in Japan for years without meeting a geisha or geisha, Macintosh offers a memorable experience that goes beyond the geisha floorshows put on for tourists in Kyoto. With the upcoming Hollywood film, he’s likely to only get busier, so catch him while you can.

Peter Macintosh can be contacted through www.kyotosightsandnights.com