“DO WHALES EAT CHIPS?” The question came from the small boy at the back of the boat. And I hadn’t heard right. It was “do whales eat ships?”

“No, they don’t,” replied the whale expert on board, “but if you harass them, or go too close to one with a calf, it could make an awful mess of our boat with its tail.”

“Whales!” interrupted an excited cry, speedily taken up by shouts of “Nine o’ clock!” All heads on our 50-foot catamaran swung in that direction. “There they go!”

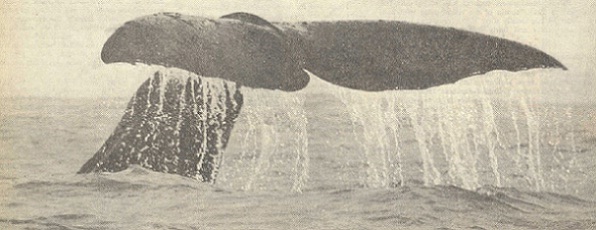

Up they came and rolled away again, surfaced and rolled until, with a final salute from those massive tails, they vanished for some 20 minutes.

The January sun was still high in the sky; the backdrop was Maui, the waters Hawaiian. And the tails belonged to Megaptera novaeangliae — the humpback whales.

When the polar waters start cooling down, the whales migrate, seeking the warmer waters of the south to mate and calve. Some go to Mexico, some to the waters off Maui and others, elsewhere.

Skin loses heat many times faster to water than to air. Blubber, a special dense form of fat that insulates the body, is designed to keep heat loss to a minimum. Humpback calves are born with little protective blubber, so need the warmer waters (and comparatively predator-free shallows) to survive their first few months.

Measuring between 12 and 15 feet at birth and weighing approximately tons, a calf needs to gain seven pounds an hour to build up the necessary blubber layer before braving the long swim back to the summer feeding grounds of Alaska. Whale milk, containing 10 times the fat of cow’s milk and with almost no milk sugar, is one of the richest in the world. It is the consistency of yoghurt.

THE YOUNG ANIMAL’S tongue forms a tube, like a straw, when pressed against the roof of its mouth — a suckling adaptation to eliminate the chances of ingesting sea water along with the milk from mammary glands, which are buried within a fold of blubber.

Born after a gestation period of 11 months, calves feed frequently. They, in turn, mature at five years and generally live to about 40 (80 recorded in one individual). An age is apparent ear.

Marine scientists class all whales, porpoises and dolphins together as whales — Cetacea. There are whales with teeth (odontocetes) and whales without (mysticetes). The humpbacks belong to the mysticetes (“moustached” whales) who have, instead, a fringed curtain hanging down from the roof of the mouth made of keratin — as in human hair and fingernails. This is the flexible whalebone once popularly used for ladies’ foundation garments. Its other name is “baleen.” In a whale’s mouth, it appears like a huge comb whose individual teeth (referred to as “plates”) feather into brushes.

THE SMALL FRY OF THE SEA cannot escape this brush-work when great volumes of gulped water is expelled through the baleen plates.

Humpbacks can exceed 50 feet in length but are generally closer to 40, weighing in at some 40 tons. Females are larger than the males; both sexes have dark, bulky bodies, narrowing only after the dorsal fin. They have throat pleats to allow for expansion when gulping water to filter their food. A humpback will engulf enough water to double its size.

Knobs on their heads and 16-foot flippers number among their distinguishing features. Patches of white mark their flippers and the ventral surfaces of their flukes and bodies. The black-and-white patterns on the fluke (the lobes of the tail) are as unique to a humpback as a fingerprint is to a human being.

After a spell of surface cruising, the whale dives, the fluke is thrown up and with its sounding, leaves a slick of calm water known as the whale’s “footprint.” About 20 minutes later, its “blow” will be the first indication of the animal’s resurfacing, erupting in a mushroom cloud of water which shoots 20 feet above the ocean surface at 300 mph. This is the whale eliminating carbon dioxide from its metabolic process. Don’t get in the way, It’s reportedly foul and full of viruses.

Whales inhale several times before diving. This is termed hyperventilating and the exchange of gases is nearly complete with each breath, compared with only 10 or 15 percent with each breath in humans. As the animal submerges, its blowhole clamps shut and the epiglotis cunningly seals off the nasal passage, allowing the whale to continue feeding while holding its breath.

Approximately half of a cetacean’s required oxygen for a dive is stored in myoglobin, a pigment similar to hemoglobin, which laces the muscle tissues. For deep dives, these oxygen stores are conserved by stopping, or slowing, blood circulation to all but critical organs. Heart rate is also slowed and, all the while, oxygen is eked out to the muscles, enabling them to continue their function.

And what about the “bends” — the condition caused when nitrogen that has been dissolved in the blood under pressure suddenly forms bubbles as the pressure decreases?

According to Dr. Sam Ridgeway, in April 1987’s National Geographic, the bends is avoided in marine mammals by not absorbing nitrogen in the first place. Dr. Ridgeway is a physiologist with the U.S. Naval Oceans Systems Center in San Diego. He explains: “The lungs of marine mammals are designed to collapse under the pressures exerted on deep dives. Air from the collapsed lungs is forced back into the animal’s windpipe, where the nitrogen simply can’t be absorbed by the blood.”

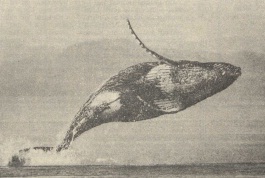

Superb in their environment, high-spirited humpbacks love to show off. Propelled by their horizontal tail, they rocket from the depths, explode through the surface of the ocean and fall back with an almighty and splashy show.

And apart from breaching, they sing!

Heads down, motionless. 50 feet below the surface, the males sing their hearts out. Perhaps their songs hold attractive information for the females? In any event, it’s thought to promote a sense of competition and dominance among the singers. It’s only the males which sing, and their songs are thought to be the longest and most complex in the animal kingdom. Listening to them sends prickles up and down your spine.

Back in 1970, their weirdly haunting and soulful songs were recorded and made into a long-playing record. More than 100,000 copies of “Songs of the Humpback Whale” were sold, keeping the Beatles and the Beach Boys on their toes.

Listening to past recordings, it was researcher Katy Payne who stumbled on the discovery that unlike, say, bird songs, whale songs are not fixed in their repeated sequences of sound. Each year the humpbacks return to Maui singing the last year’s song and, as they sing, new pieces are added, other parts modified, thereby altering, subtly, the song as it’s being sung. Over the years new songs evolve.

Back in the polar latitudes, where the humpbacks’ feeding grounds are seething with krill, the whales gorge themselves night and day in a bid to build up their blubber layer. The blubber not only sustains them during their long migratory routes, but also during their months in Hawaii when even the nursing mothers “fast.”

As an alternative to gulping for krill, humpbacks occasionally employ the trick of surrounding schooling fish with a net of bubbles, then surfacing in their confused midst to scoop up the lot.

Their daily catch? A ton, at least.

Between 400 and 600 humpbacks visit Maui annually, roughly from December to May. Interestingly, there is no reference to whales in Hawaian mythology which, for culture bound so closely to land and sea, would indicate that whales were not part of the Hawaiian scene before the 1800s.

Now, since the cessation of their outright slaughter, sightings of humpback groups, or “pods,” have been greeted with relief and increasing pleasure— but busier whale watch cruises! Protests have been voiced: the whales have chosen Maui, let’s not drive them away. Legal approach limits of 300 yards, and 100 yards if there’s an absence of calves, must be observed.

Trailing 300 yards behind, the pods we saw were quite small, usually two or three whales. There is no life-long attachment between males and females, and which animal fathered whose calf would be anyone’s guess. The only longterm pod is the cow and calf; there is no jealousy or aggression shown to the calves by the adult males.

An “escort” often makes the third member of a pod. Escorts tend to hang around, waiting for the female to become receptive. When challenged by other males, a “surface-active group” is formed, battling over the female. Tail lashing is likely to follow and body smashing, resulting in bloody head knobs, fins and flukes.

In normal circumstances, however, the vast majority of whales are non-aggressive. Only a diver’s bubbles might be interpreted as a sign of aggression since whales, themselves, signal aggression in this way.

“Friendly” whales will make themselves known and once used to you, they may start to play. This could rock the boat.

Cetaceans are known to help one another out (epilemetic behavior) in times of stress. A male, seeing a boat approach a female and calf, is likely to place itself between the “threat” and the pod. Two separate accounts tell of a calf stranding itself on a sand bank and being instantly joined by two cows, which sandwiched the youngster and maneuvered it back into the water.

A mother whale is not above chastising, with a slap of a flipper, a frolicking juvenile intent on disrupting her afternoon nap! In exasperation, right whale mothers have been seen (o roll over and hold their respective calves between their flippers to quiet them.

In their embryonic form, all cetaceans have hair, grow the hind legs of a terrestrial mammal and possess traces of teeth in varying degrees. All of these disappear as the fetus develops. In mysticetes, baleen plates have evolved, but although these may replace teeth in function, they do not replace the teeth which vanish in later fetal development.

Despite the fact that scientists are still disagreeing on the classification of cetaceans, it was largely on account of their dentition that they were classed as either baleen, or toothed whales.

Cetaceans are carnivorous, the baleens straining zoo plankton from the sea, while their toothed whale counterparts (of which there arc far more species) chase and seize bigger prey. Food passes, unchewed, into a multi-chambered stomach — a stomach reflecting ruminant origins, unfortunately so obscured by evolutionary dead-ends, that links between ancient and modern whales cannot be satisfactorily traced.

Nevertheless, composition of the modern whales’ blood serum protein would seem to support this relationship with the ruminating order. Artiodactlyta. And the artiodactyle closest to the whale is probably the hippo.

Due to the buoyancy of the water, the sea is the only medium able to support the great whales. The blue whale, which can take in 70 tons of water in one gulp and whose tongue weighs more than an elephant, is larger than the largest dinosaur. No bones are strong enough to support their weight on land and, once stranded, no muscles arc strong enough to expand their chest for breathing.

In their struggle for survival, the biggest dinosaurs lived a semi-aquatic existence.

Sound is more important to cetaceans than vision in their ocean environment. They “see” with their sonar system. At least, the odontocetes do. Among the great whales, only the sperm is a toothed whale — all the rest are baleens, like the humpback. Although humpbacks emit an intriguing variety of sounds, no evidence yet discovered proves they can echolocate in the manner attributed to the odontocetes.

What are the dangers to the humpbacks? Huge ocean drift nets and some whaling off Greenland and the small Caribbean island of Bequia. As an endangered species, humpbacks have been protected from full-scale whaling since 1966. Killer whales and their false killer whale cousins pose a danger to humpbacks and other whales. Usually the sick, injured or just plain lazy are singled out for attack.

Killers, like wolves, hunt in packs. False killer whales have been seen killing a humpback calf in Hawaiian waters. Cookie cutter sharks also pester the humpbacks; they latch on, twist round and come away with a lump of flesh, leaving a round wound. Nasty.

…So, do whales eat ships? Not literally, but ships still chase whales. Greenpeace boats intercept when they can but the question remains — will the last of the whales survive the last of the whalers?

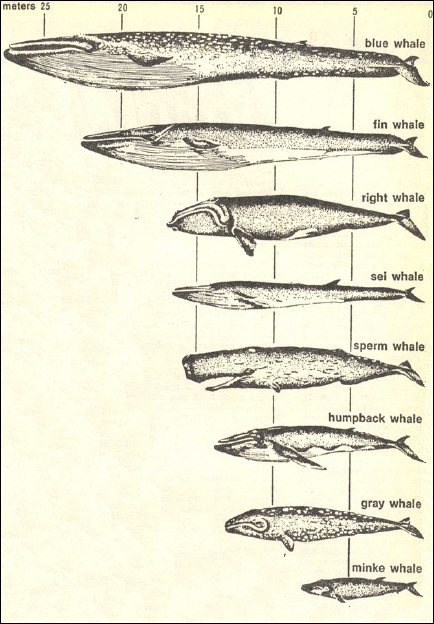

The BLUE whale is the longest and heaviest animal in the world, larger even than the largest of the dinosaurs. Although quick and agile, blue whales have been slaughtered indiscriminately since the start of modern whaling technology. They feed mostly on common krill and аre protected in all oceans.

A rapid swimmer, the FIN whale was not successfully hunted until modern times. Protected in all waters except the North Atlantic, fin whales eat common krill, small fish and squid.

Because of its slow speed and thick skin causing it to stay afloat after death, the RIGHT whale was killed indiscriminately during the era of sailing-vessel whaling. Feeding mainly on animal plankton, it is now protected by a total ban on hunting in all waters.

SEI whales feed mainly on common krill and calanus, a small crustacean. It is thought to inhabit all waters and its catch is banned in all areas except the North Atlantic.

Of all whales, the SPERM whale can dive deepest and longest. It feeds mostly on squid and has been hunted since the advent of American sailing-vessel whaling. Now, partial and total moratoriums exist in all waters except the North Atlantic.

Slow swimmers, HUMPBACKS were decimated during sailing-vessel whaling times. The humpback feeds mainly on common krill and fish and is presently completely protected.

The GRAY whale is found only in the North Pacific, migrating through North American coastal waters, the Bering Sea, and the arctic, feeding on sea slugs and demersal fish. Gray stocks were dangerously depleted in the 19th century. Now protected, its numbers have increased. Hunting is prohibited except by indigenous inhabitants of the Soviet arctic.

The MINKE whale lives throughout the world’s oceans, feeding mostly on krill. Stocks are presently increasing; the IWC allows its catch.