THE JEWS & ART

by Fred Harris

“Thou shall not create a graven image” — For as long as history has been recorded, the western world has assumed that the second Commandent meant that Jews could not represent God’s image of Man. Yet how does that explain the predominance of Jewish artists in our past century? In relationship with the world’s population, the number of well-known artists who happened to be Jewish is a very startling ratio.

Just think of this slate of names: Pissarro, Delaunay, Epstein, Kisling, Lipchitz, Modigliani, Pascin, Soutine, Zadkine, Chagall, Baskin, Bloom, Rothko, Mane-Katz, Hundertwasser, Shahn, Soyer, Levine. To those the least bit knowledgable about art, the above list reads like a “Who’s Who” in 20th century art. Why so many, and what is the motivation, when for centuries it was assumed that it was a forbidden area to tread upon?

From the sun-drenched landscapes of Camille Pissarro who led the impressionists through their years of turmoil to the expressionism of Mane-Katz and Marc Chagall, the stark abstracts of Marc Rothko. Jews have participated in the visual arts in a very positive way. A quick browse through any recent issue of Art News magazine will reveal a predominance of Jewish names amongst the artists exhibiting in today’s galleries.

What causes this unique phenomenon? Jews were not supposed to produce a pictorial image—yet it has happened.

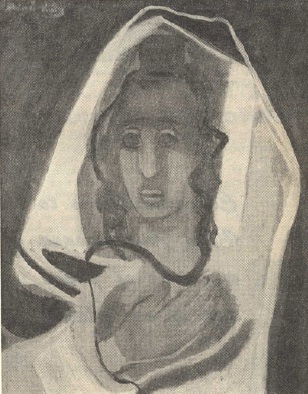

The answer is two-fold. First the ritual of the synagogue is visually exciting. The patterns of the white prayer shawls with their bold black or blue stripes creates almost a cubist composition. Flesh tones and beards peep out from the cloth. The morning light pouring into the interior from the east window of the house of prayer highlight this maze of color and emotional expressions of men at prayer. The glitter of the ornaments which cover and crown the scrolls adds to this picturesque excitement. This combination of ceremonial objects and dress cannot but inspire an artist to record his impression of what is around him.

Even a non-Jewish artist as Rembrandt devoted a good portion for his work is portraying Jewish themes, using as models the elderly from the Jewish quarter in Amsterdam.

His familiarity with this community also brought him many commissions including one from Saul Levy Morteira, Chief Rabbi of the Amsterdam Portuguese Congregation from 1616 to 1660.

The second reason may be attributed to the imagery created by the poetry found in the prayer books which causes the mind to drift into a visualization of what is being read. Such passages as, ‘Were our mouth filled with song as the sea is with water, and our tongue with ringing praise as the roaring waves; were our lips full of adoration as the wide expanse of heaven, and our eyes sparkling like the sun or the moon; were our hands spread out in prayer as the eagles of the sky and our feet as swift as the deer…” or, “Were the skies parchment, were all the reeds quills, were the seas and all waters made of ink…”

The creative act which wrote this poetry centuries ago continues today in many artists who think visually as well as orally.