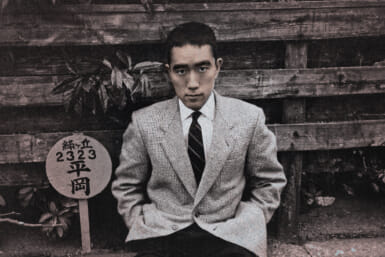

by Yurie Horiguchi

This is the time of the ear when the Japanese enjoy (?) scaring each other with ghost stories.

There seems to be a fixed ritual in this country about what can or cannot be done, used, worn or eaten during specific seasons.

For instance, I was looking for small ashtrays the other day and came across some very pretty glass ones. The salesgirl was quite enthusiastic about my buying them assuring me that they would make “lovely summer ashtrays.”

But to get back to our ghosts or obake, or yurei (not to be confused with Yurie please, Mr. Proofreader) .

Before the days of air-conditioning and electric fans, ghost stories were particularly popular in the hot summer months because they made the audience shiver with fear and forget the heat.

And of course the best time for telling them was in dark gardens on summer evenings. In fact, through the Tokugawa and Meiji Eras, ghost story-telling parties were often held with the host playing tricks to scare his guests.

For instance, a sudden wind would blow out the candles, or something wet and clammy would pass over one’s face or neck, or a weird sound would be heard, such as a woman’s sobbing or wailing. Definitely not the sort of party for the chicken-livered to attend.

The ghost season really starts with the O-Bon season when the spirits of the dead return to their homes “by invitation” as it were. For Japan’s dead are blessed with the opportunity to return from the “other world” once a year to revisit the families of their descendants, between July 13 and 16.

These visiting spirits are the good ones. The baddies which come uninvited are the yurei, or obake and they generally come in a vengeful mood to scare the sanity out of those who wronged them during their time on earth.

Since the days of the Tokugawa Shoguns, obake plays have been performed on Kabuki stages while story-tellers have billed tales of ghosts in summer to chill the spines of those who enjoy such esoteric pleasures.

In very old times, Japan’s ghosts, like Western ghosts, were believed to materialize in the exact form and apparel they wore in life. As time passed, however, ghosts decided to become more scary.

They probably held a convention to decide what the “new line” for the next millenium would be, and voted for an all-white era.

So they started appearing wearing their white death-shrouds or shinishozoku, with a triangular piece of cloth (white) tied over the forehead. They came with pale, haggard faces, masked by long black hair falling over their shoulders, to waist-length.

The most notable feature about them is that they have no legs, the lower body tapering to a narrow, waving end. Their arms are raised like those of a sleepwalker, with the hands and fingers limply drooping downward.

If in doubt, look and see if it has feet or not. If it has, it isn’t the real thing.

Obake are thought to have the ability to fly at will through space, and for the accomplishment of their vengeful purpose will follow a person anywhere.

The time for their appearance is generally limited to around 2 a.m., this limitation being one of their characteristics. But as yurei appear only to the eyes of such people as have reason to be haunted, those who live good, clean lives are fairly immune.

However, there are other ghosts that you or I could meet in the early hours should we be disposed to traipsing around at 2 a.m. These are the spirits of people who have met with some dreadful end. and haunt the site of their death – whether in the open or in a certain room.

In paintings, obake are often depicted under the branches of a weeping willow tree, which supposedly adds to their eerie appearance. Also, balls of greenish-white fire with long flaming tails are seen around them.

These are called hino-tama or hito-dama, which is the form that a person’s spirit is believed to take immediately after death. Quite a few people claim to have seen these balls of fire floating over their roof-top after the demise of a member of the family.

Perhaps the most famous Japanese ghost story, which is not only a Kabuki play but also a theater piece as well as a movie, is Yotsuya Kaidan, or the Ghost Story of Yotsuya.

The heroine (?) is the ghost of O-Iwa. O-Iwa (who, incidentally, is supposed to have really existed) was the lovely and demure wife of a philandering samurai named Tamiya Iemon.

When O-Iwa reproaches him for his illicit affair with another woman, he decides to poison her. However, the poison only partially succeeds, and poor O-Iwa becomes most horribly disfigured.

Not being able to live with her own image and her husband’s infidelities (not to mention his murderous intents), she commits suicide.

Her ghost, with its ghastly disfigured features, returns almost immediately to eventually hound her hushand to his own death, and the death of many others in between.

Strangely enough, it is believed in certain circles that the curse of O-Iwa still exists. and whenever a theater decides to produce the play, actors and theater managers visit O-Iwa’s tomb to offer prayers and ask for her permission to stage the show.

In all events, the O-Iwa Inari Shrine at Samon-cho, Yotsuya, where she once lived and was first buried, as well as the Myogyo-ji (temple) at Nishi Sugamo, where her tomb was later transferred from Samon-cho, are constantly visited by theatrical people as well as by writers and others who wish either to produce the Kabuki play or write about poor O-Iwa-san.

I’m on my way there now.