Keisuke Hirata sits across from me, perched on a low stool. He’s wearing a sheer cardigan today. The artwork inked on his arms is visible through the fabric, which ripples with deep purples and bruised reds, occasionally interrupted by a burst of pale blue.

The air around us is dense with a mix of tobacco smoke and a burning candle, something woody and earthy — maybe cedar. It clings to the room, familiar. A tattoo bench sits to my right, next to trays of ink bottles and sterilized needles gleaming in silver silence.

This is Flat Tattoo Room, Keisuke Hirata’s studio, where doodles find permanence on living skin. Here, he expertly merges playful designs with traditional stick-and-poke techniques, earning him acclaim as a rising tattoo artist in Tokyo.

Keisuke Hirata

Hirata’s voice, when he speaks, is soft, despite the packs of cigarettes that lie scattered around the room. Plants lean toward the weak afternoon light, their leaves brushing the window panes, as if they, too, are waiting to hear what he will say next.

The surprising sense of gentleness that effuses from Hirata is reflected in his tattooing style; as a stick-and-poke artist, he works by dipping a needle in ink and pressing it into skin with a gentle hand. His work is light, whimsical, almost surreal, like something out of a strange dream. The walls of his studio are a patchwork of these quirky sketches: a man morphing into a flower, a lopsided building, a globe sprouting from a tree. Each one looks like it was plucked from a daydream, or maybe a napkin sketch made over coffee.

This stands in stark contrast to the tattooing technique he grew up around. Before moving to Tokyo, he began working in his hometown of Asahikawa, Hokkaido, about four years ago. Asahikawa was wabori territory — bold, thick-lined, traditional Japanese tattoos. Dragons coiled in fierce poses, tigers prowling down arms. Tattoos that speak of power and masculinity.

“You’d see yakuza everywhere covered in these tattoos. Wabori does have its own charm, but after a while, I started to get tired of seeing the same thing,” he says. “I wanted something different, something softer, the antithesis of all that rigidity.”

I ask about his choice to hand-poke rather than use a machine. “It’s intimate,” he says. “Putting in each line, one by one, with care. There’s a closeness to it. It’s not just about getting a tattoo and then ‘bye-bye.’ It feels more human.”

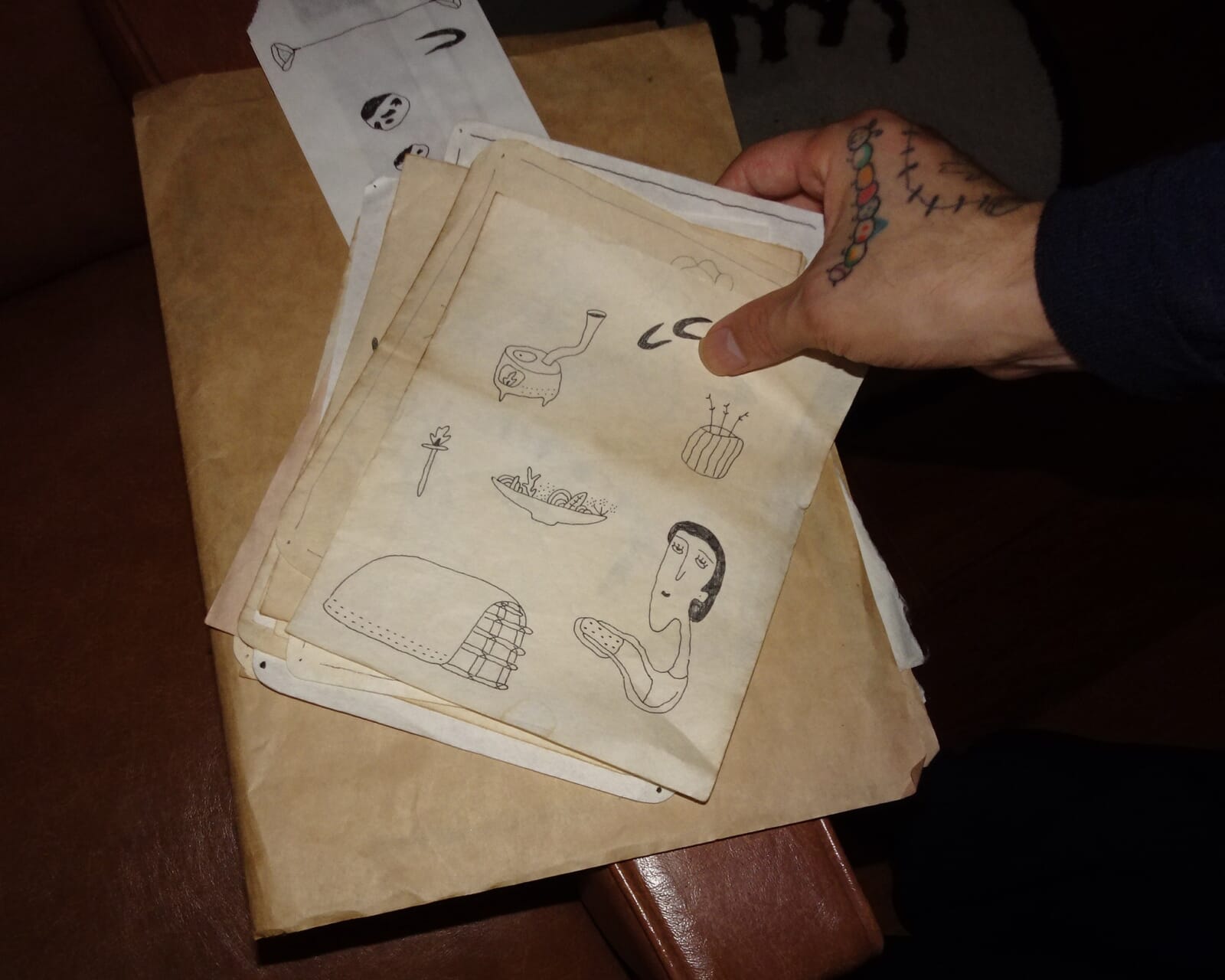

Hirata’s designs

One of my first tattoos, in fact, was designed by Hirata. The piece feels like an extension of myself, with lines slightly marbled to meld seamlessly with my skin rather than being a solid black.

I walked into his studio in the winter of 2022 with a design in mind: I had told him that I wanted a portrait inspired by one of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s self-portraits. When I arrived, he sat me down on a cream-colored cushion and placed six hand-cut sketches on a low table. Each one was a delicate exploration of my idea, capturing the essence of Basquiat while incorporating Hirata’s signature touch — graceful dots and fluid curvatures that softened the edges and made the design unmistakably his. I chose the one adorned with his trademark little flower.

The art he creates feels deeply personal, tailored to each individual. It’s more like an art session with a friend than a transaction. To this day, I still have the paper he used as a stencil for the tattoo — I carry it around in my wallet as a keepsake. When I mention this to him, the little flower tattoo on his left cheekbone crinkles slightly as he smiles.

I press him on the most memorable tattoo he’s given, expecting a profound tale. But he surprises me. “I’ve done tattoos of cakes and cookies because people have had a great dessert the day before.”

There’s a moment of silence as I blink, unsure if he’s joking. But the glint in his eye says otherwise. “I love to see that,” he continues. “Going with whatever feels right in the moment. That kind of freedom is rare in Japan.”

Tattoos are slowly gaining traction in Japan, but the stigma runs deep. The negative connotations are a remnant of the association between tattoos and the yakuza, or the Japanese mafia. Even now, public baths, gyms, even beaches sport the telltale signs: No tattoos allowed.

Hirata understands this cultural tension but approaches his work with a refreshing subtlety. He isn’t out to shock or provoke; instead, he aims to foster quiet acceptance and the recognition that we all carry stories on our skin, whether inked or invisible.

“Things are changing, slowly,” he says. “Tattoos always spark opinions. One person loves it, another hates it. That’s normal. I just want people to relax. We’re all on different paths, and everyone expresses themselves in their own way. Why not let those expressions be?”

His carefree approach underscores a significant cultural shift: as tattoos become more normalized, they begin to transcend their past associations. He’s part of a new wave of artists in Japan who see tattoos as personal expressions rather than rebellious statements. His hope is that, one day, tattoos will just be seen as choices.

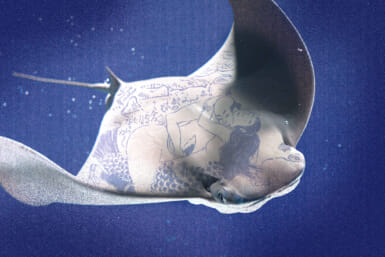

Via @flattattooroom

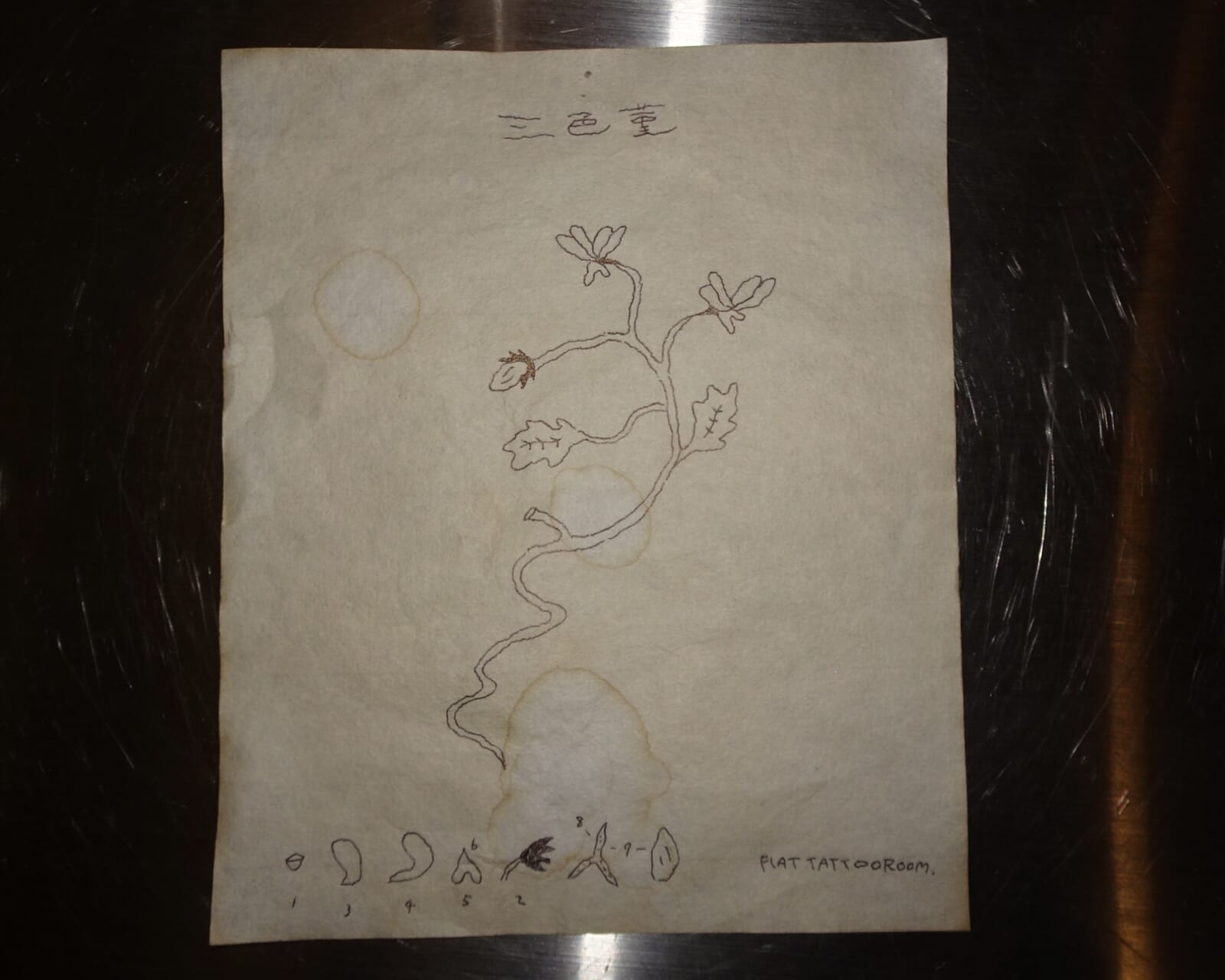

Despite his casual attitude and whimsical style, in many cases, the simpleness of Hirata’s designs belie their emotional depth. He draws inspiration from the artist Shibusawa, whose work evokes the haunting beauty of Victorian flowers found in children’s fairy tales. These blooms at first seem to be just flowers, but the more you look at them, the more they take on unsettling allure, echoing the Victorian era’s flirtation with the forbidden. “Shibusawa draws flowers in a way that’s almost sadistic, sexual, almost,” he says. “I’m drawn to that tension, the way desire dances around the border of pleasure and pain.”

Lately, he’s been drawing sofas. For him, the simple piece of living room furniture becomes a symbol for vicissitudes of domesticity, of seeking romantic comfort and support. He’s drawn many of them over the past few months: bouncy sofas, worn sofas and even a sofa that turns into a door. The door-sofa, with its gentle curvature, seems to defy the laws of physics, floating in midair like a cloud. Dotted lines outline its form, softening the edges.

“I was in this relationship, and then this other woman came along, wanting an open, three-way relationship. We tried it for about a month. But come to find out, I hated it,” he says. “After we broke up, I started drawing sofas. I used it as a way to express the situation — turning half of the sofa into a door, something symbolic. Part comfort, part escape.” His art, much like his relationships, pulls from the everyday, often convoluted moments of life. A sofa, of all things, becomes a vessel for his emotional turmoil.

Hirata’s flowers

Like Hirata’s work, the evolving tattoo scene in Tokyo exists in a space of overlapping tensions. Tattoos, once symbols of rebellion or danger, are now slowly shedding those connotations, finding new expression and acceptance in the hands of artists like him. Yet, they continue to reside within a realm of transgression and taboo, at least for now. It’s this contradiction — the almost paradoxical merging of the forbidden and the everyday — that appeals to Hirata.

“I think it’s that in-between space that fascinates me,” he says. “Opposites — love and hate, beauty and decay, pain and pleasure, the desire to live and the desire to die — they’re closer than we think. It’s where they touch that things get interesting.”

In this quiet studio in Yoyogi, acceptance and desire find expression in the fine lines etched dot by dot into living skin.

Follow Keisuke and his work on Instagram @flattattooroom.

Flat Tattoo Room