Kyosai Kawanabe is perhaps the most fascinating and unique artist of the Meiji Era (1867-1912) in the transition from old to new Japan. A master creator of both the natural and supernatural world, he was drawn to both the humorous and horrible, which followed him from an early age.

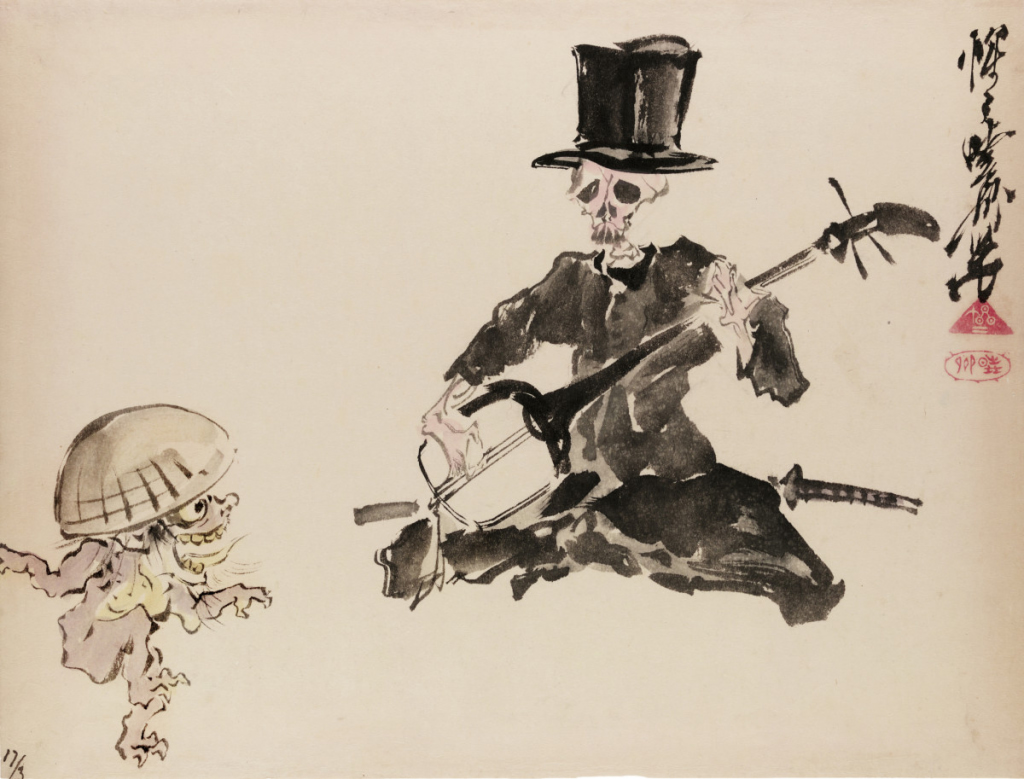

Kyosai was a very skillful and prolific artist, producing thousands of paintings, prints and drawings during his lifetime. His subjects included crows, tigers and elephants, demons, frog acrobats, tengu, the seven gods of fortune, ghosts and dancing skeletons, along with the more serious types such as Shoki the demon queller, the King of Hell and the Zen patriarch Daruma.

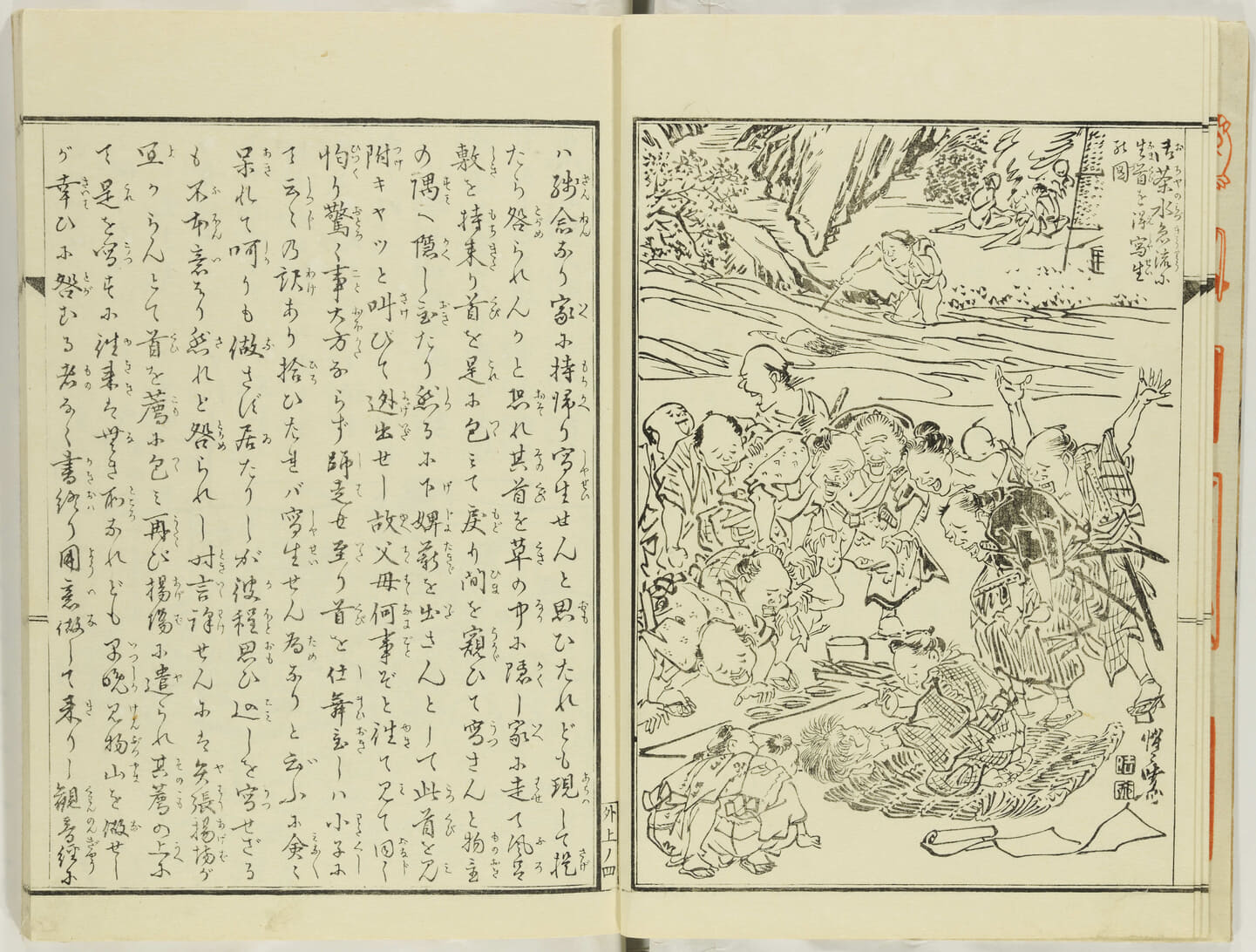

‘Finding a Severed Head in a Rushing Stream at Ochanomizu and Sketching It’, in Kyosai’s Account of Painting (Kyosai gadan), vol. 1 of part 2, 1887

Colour woodblock-printed book, 25.2 x 17.6 cm (cover)

Israel Goldman Collection, London. Photo: Art Research Center, Ritsumeikan University

The Beginnings of Kyosai’s Inspiration and Work

When Kyosai was just nine years old, he came across the severed head of a man in Kanda River. Although initially shocked, he pulled it out of the water and brought it home to sketch. This was an event that understandably left a strong impression on the young boy and one he would return to as a subject later in life.

He initially apprenticed as a seven-year-old to ukiyo-e artist Kuniyoshi Utagawa (1797-1861), who represented the common person and anti-academic. At the age of 10, Kyosai began to study academic painting as part of the traditional Kano school.

Having received training from two opposing schools, Kyosai’s works clearly reflected influences from both traditional Japanese art as well as popular culture. As an artist, he manifested versatility, not only in technique but in the choice of subjects that balanced between the old and new during a time that saw Japan transform from a feudal society under military rule to a modernized nation adopting western political, financial and military systems.

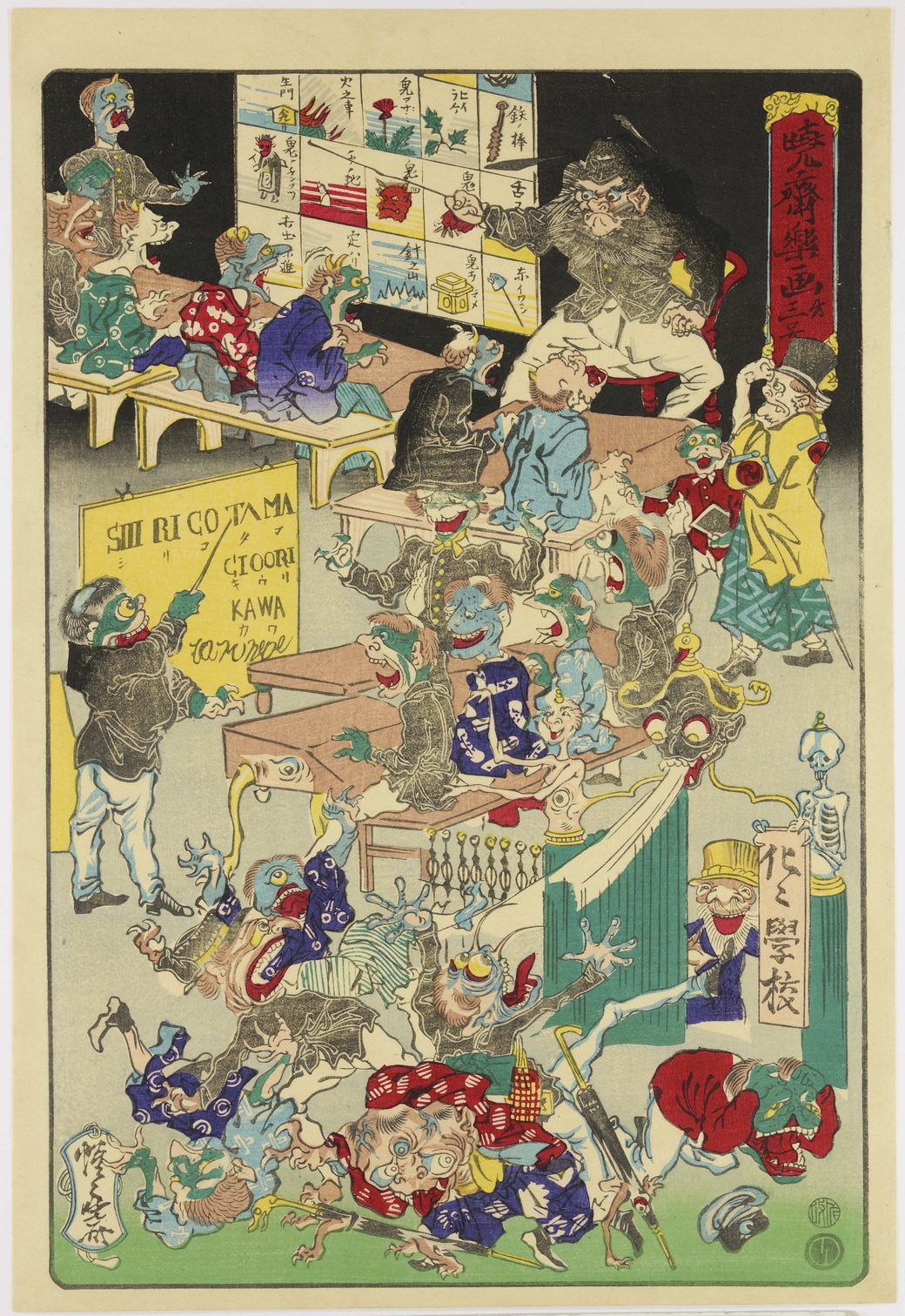

‘School for Spooks’ (Bakebake gakko), no. 3 from the series ‘Drawings for Pleasure by Kyosai’ (Kyosai rakuga), 1874

Colour woodblock print, 36 x 24.5 cm

Israel Goldman Collection, London. Photo: Art Research Center, Ritsumeikan University

Kyosai and the West

Although initially critical of the rapid changes to Japanese society, which Kyosai often depicted with a strong sense of humor, he also embraced his encounters with Western culture. He contributed works to several of the world exhibitions during the second half of the 19th century: Vienna (1873), Philadelphia (1876) and Paris (1878), as well as taking on a westerner as a student.

Josiah Conder was a so-called oyatoi – a foreigner hired by the Japanese government during the Meiji Era when everything Western came into fashion. He arrived in Japan in 1877 to teach architecture at the Imperial College of Engineering.

Conder was the architect behind Japan’s first National Museum, which was sadly destroyed during the 1923 Kanto earthquake. It was as part of the Second National Industrial Exhibition in 1881 – in which Kyosai participated and won the highest prize.

After many requests, in a reversal of roles, Kyosai finally accepted Conder as his student. As their relationship grew, Conder would also become a close friend and patron with many of Kyosai’s works ending up in Conder’s collection. In 1911, Conder published Paintings and Studies by Kyosai, one of the most important sources on Kyosai’s life and work.

While Katsushika Hokusai was – and probably still is – the most recognized Japanese artist in the West, he was long gone by the time Japan opened up to visitors from outside. Kyosai on the other hand, was very much alive and accessible and he met with many foreigners living in or visiting Japan.

That included the painter Mortimer Menpes and British surgeon William Anderson, who commissioned works directly from Kyosai (which he sold to the British Museum in 1881 as part of a bigger Japanese art collection). There was also the French industrialist and founder of Musée Guimet in Paris, Émile Guimet, who visited Kyosai at his home in Tokyo during his travels in 1876. He was joined by the artist Félix Régamy, who ended up having a draw-off with Kyosai.

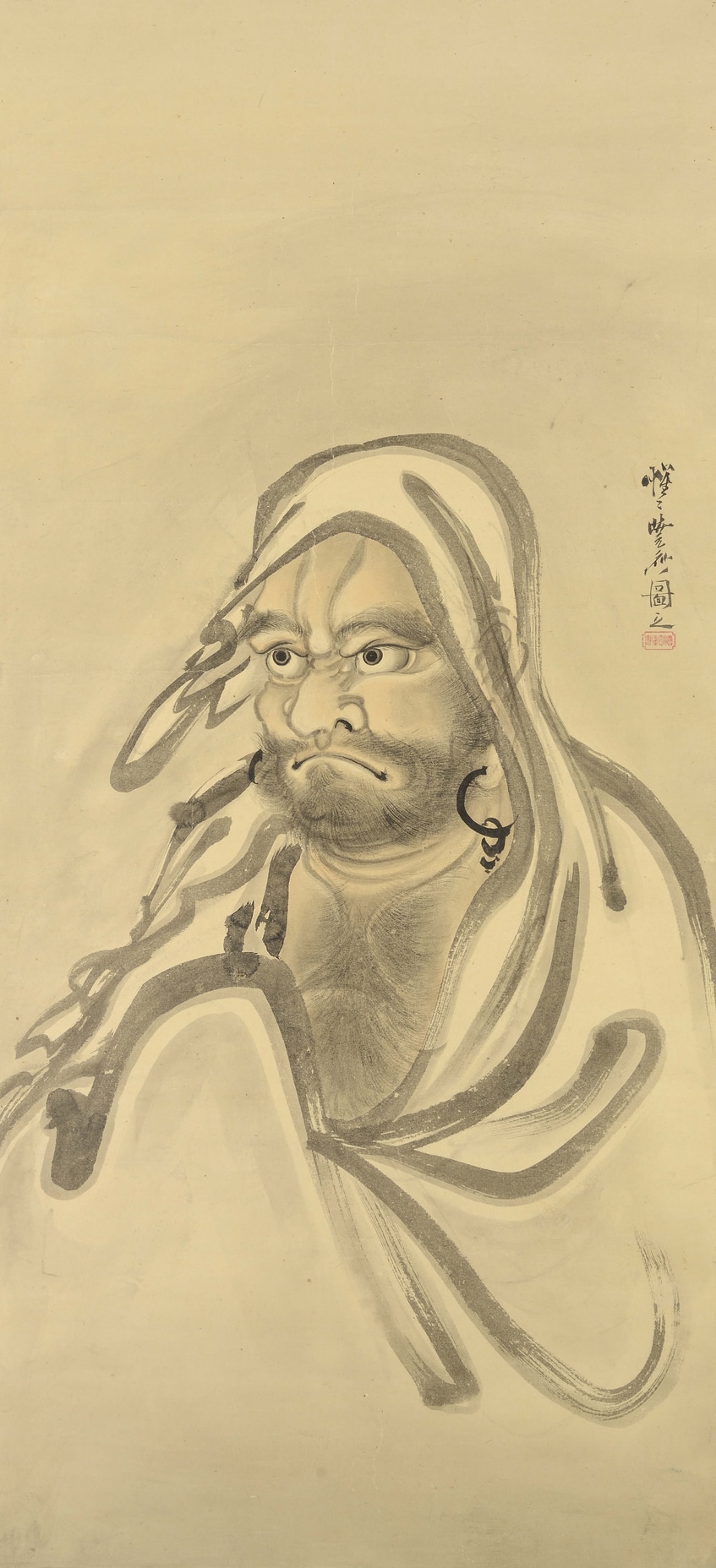

Daruma, 1885

Hanging scroll: ink and light color on paper, 127.5 x 58.4 cm

Israel Goldman Collection, London. Photo: Art Research Center, Ritsumeikan University

Considering Kyosai’s many connections to foreigners and their appreciation of him and vice versa, it’s not surprising that a westerner is one of the most significant Kyosai admirers and collectors of our day.

In the early 1980s, just a little less than 100 years after Kyosai’s death, the young American ukiyo-e dealer Israel Goldman came across his first painting by Kyosai at an auction. Goldman had previously purchased Kyosai prints (also purchased by the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), but this was a major work by Kyosai — and Goldman’s first major discovery — estimated at just £30-50. A hanging scroll picturing the Zen patriot Daruma painted in 1885, for which Goldman, in the end, paid £55, was to be the beginning of a long and inspiring collectorship of Kyosai and one of the world’s finest and representative collections of his works.

Kyosai: The Israel Goldman Collection Exhibition 2022

On 19 March this year, “Kyosai: The Israel Goldman Collection” opened at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. The first exhibition on Kyosai outside of Japan in almost 25 years, it emphasizes all aspects of Kyosai’s oeuvre in different media as well as subjects. The show is curated by Kyosai scholar Dr. Sadamura Koto who has also written the two accompanying catalogs presenting works of which at least a quarter has not previously been published. The exhibition will run until June 19, 2022.

In Japan, you can always view Kyosai’s work at the Kawanabe Kyosai Memorial Museum in Saitama. The museum is owned by a grandchild of Kyosai and exhibits artworks of the ukiyo-e master and his daughter, Kyosui Kawanabe, a nihonga painter.