The first Japanese winner of the Pritzker Prize, Kenzo Tange was unquestionably one of the most influential architects of the 20th century. Inspired by the creations of Le Corbusier (born Charles-Édouard Jeanneret), Tange’s work struck a balance between modernism and traditional Japanese aesthetics.

On the 20th anniversary of his death, we are looking back at the life and times of the man responsible for iconic works such as the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, the Yoyogi National Gymnasium and St. Mary’s Cathedral.

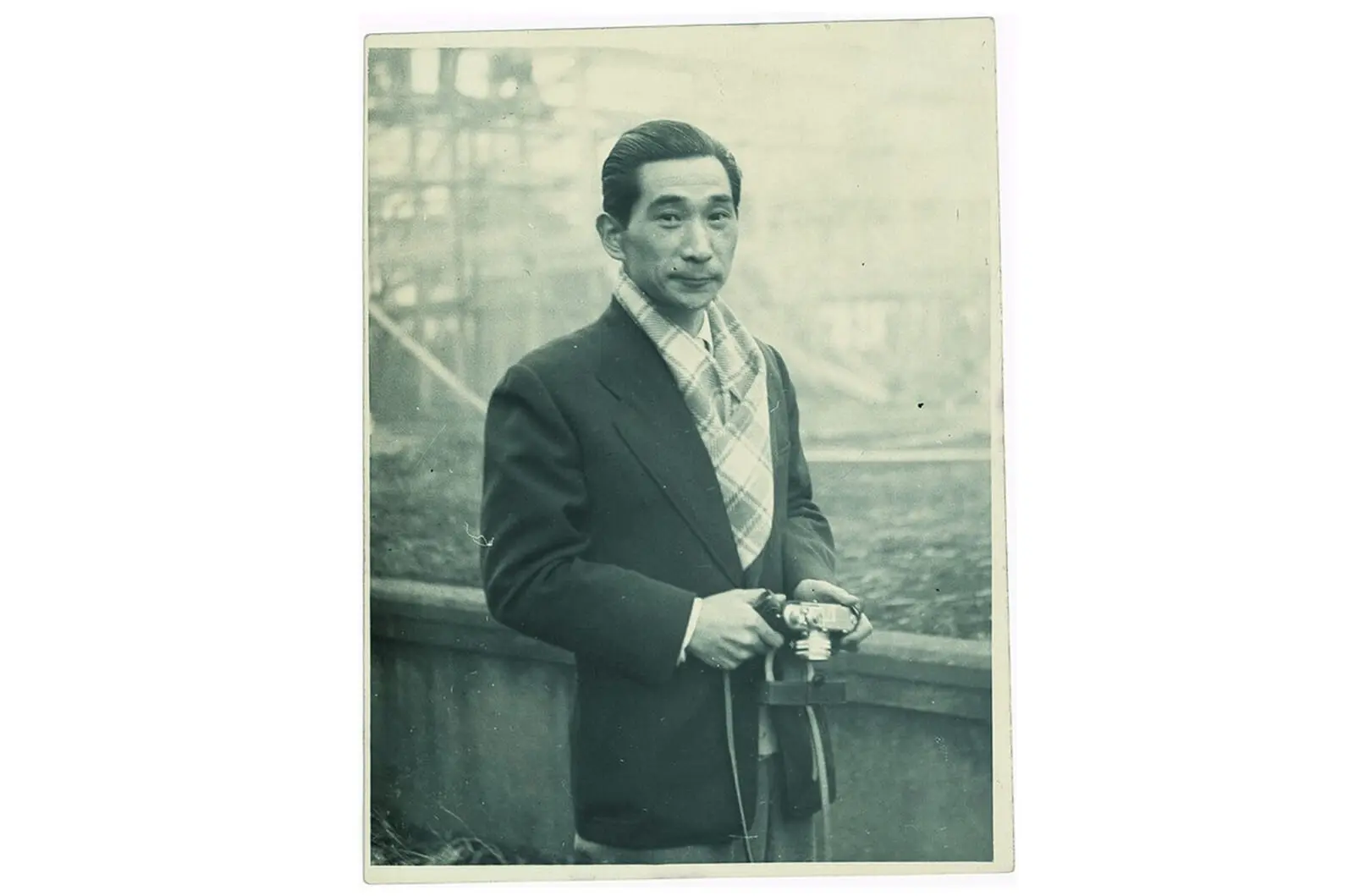

Kenzo Tange c. 1953 | Wikimedia Commons

Kenzo Tange’s Background

Tange was born in Sakai, Osaka Prefecture, on September 4, 1913, but spent his early years in China due to his father’s work. The family moved back to Japan in 1920, settling in the port town of Imabari on Shikoku Island.

A decade later, Tange headed to Hiroshima to study at high school. That was where he first saw Le Corbusier’s proposal for the Palace of the Soviets, which was rejected in 1932. He discovered it in a foreign art journal and was immediately astounded. The teenager subsequently enrolled in the department of Architecture at Tokyo Imperial University.

After graduating, Tange worked in the architectural design office of Kunio Maekawa. A former pupil of Le Corbusier, Maekawa was a pivotal figure in the development of modern architecture in Japan after World War II. It would be his protégé, though, who would go on to become the country’s leading architect.

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park

One of Tange’s earliest and most famous projects was the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, which opened on April 1, 1954. The idea to construct a peace memorial site and preserve buildings situated near Ground Zero of the atomic bomb explosion came from American park planner Tam Deling seven years earlier. In 1949, an international design competition was held with 132 entries. Tange’s proposal was selected as the winner.

The north-south axis of peace, which includes a cenotaph for victims of the attack, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and the A-Bomb Dome — the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, originally designed by Czech architect Jan Letzel in 1915 that remained standing despite the bombing — serves as a visceral reminder of the destructive force of nuclear weapons and the suffering caused by war. The site is visited by more than 1 million people annually.

“After an arduous effort, he decided to use the idea he drew on the back of a cigarette pack,” Sachio Otani, who assisted Tange on the project, told The Chugoku Shimbun. “By chance, the cigarette brand was called ‘Peace.’ This design became the prototype for the park and featured the Atomic Bomb Dome on an axis in line with the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims and Peace Memorial Museum. It was an extraordinary idea, embracing the A-bomb Dome as the symbol of the atomic bombing experience as well as the ‘banner’ of the reconstruction of Hiroshima.”

The Yoyogi National Gymnasium

By the early 1960s, Tange was considered the “West’s favorite Japanese architect.” He and his students led the Metabolist movement, which envisioned buildings and cities as adaptable, organic entities that were capable of regeneration and growth. Influenced by the city’s population boom and evolving needs, Tange proposed “A Plan for Tokyo 1960.”

Exemplifying the ideals of the Metabolist movement, it called for a new spatial order in the form of a linear megastructure with interlocking loops across Tokyo Bay. Despite impressing both Japanese and international audiences, it was a utopian plan that was more symbolic than practical. It did, however, act as a precursor to Tange’s later works, including the Yoyogi National Gymnasium, built for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

That was the venue for swimming events at the 1964 Games, as American teenager Don Schollander emerged as one of the biggest stars of the Olympics with four gold medals. It also hosted diving, while the annex held the basketball competition. When Tange received the Pritzker Prize in 1987, the citation described it as being “among the most beautiful buildings of the 20th century.” At the time, the high-tension suspended roof structure was seen as groundbreaking. More than 60 years on, and it remains a timeless architectural marvel.

“It’s kind of a miracle,” Professor Souhei Imamura, who teaches architecture at the Chiba Institute of Technology, told The Mainichi. “It combines structure, form and also function. Each is unique and they are blended. Dynamism was required at the time because Japanese society wanted to change, to evolve. The dynamism was also needed for those Olympics.”

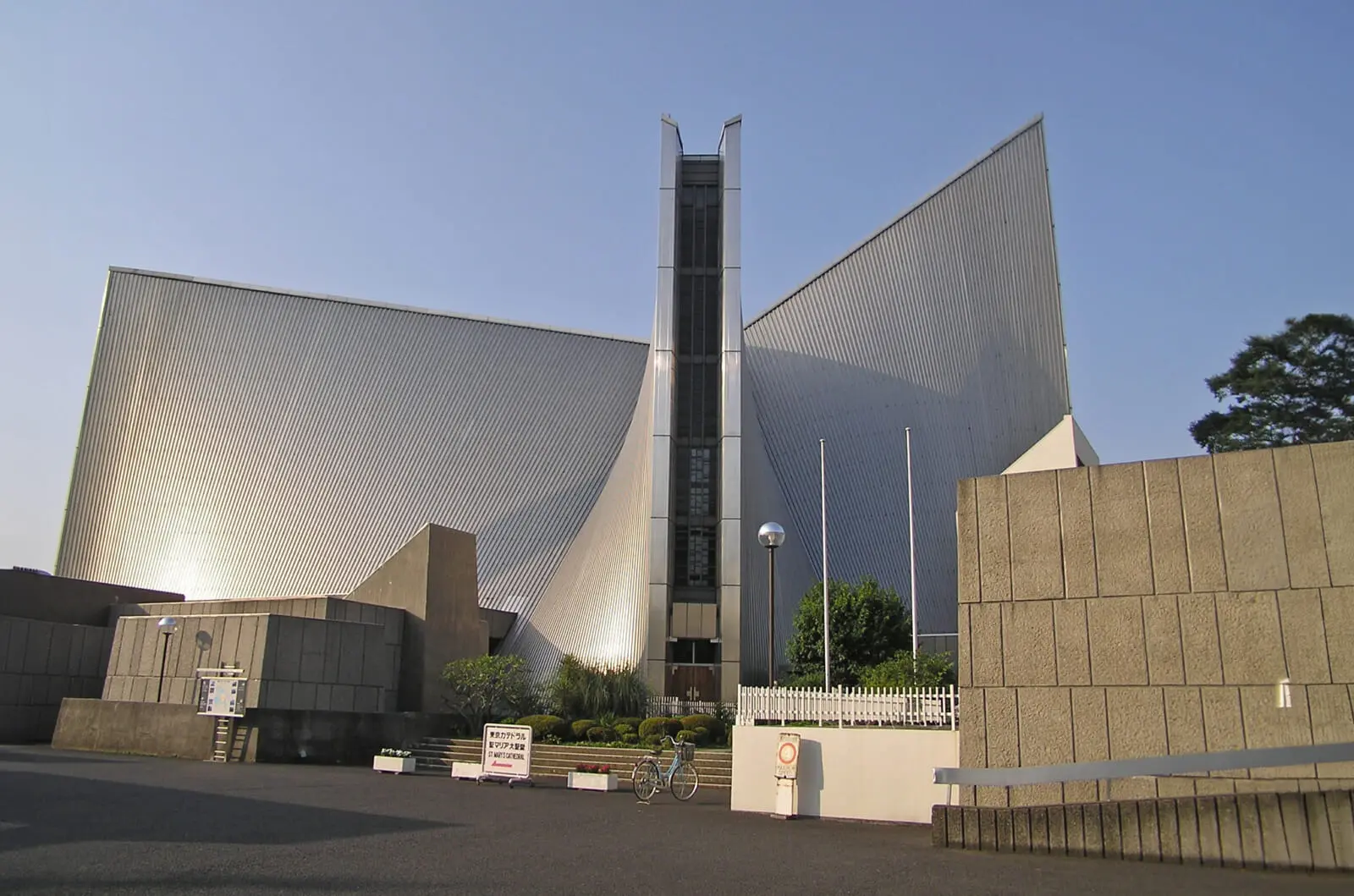

St Mary’s Cathedral, Tokyo

Other Notable Projects

Less than two months after the Olympics had finished, another of Tange’s famous buildings was completed. St. Mary’s Cathedral, Tokyo, is made up of concrete covered by stainless steel and eight curved walls, which form a large cross. It was a replacement for the Tokyo Cathedral — built in 1899 in a Gothic style — which survived the Great Kanto earthquake of 1923, but was destroyed during the Tokyo air raids of World War II.

A competition was held between Tange, his mentor, Maekawa, and another star architect of the time, Yoshiro Taniguchi. Tange’s winning entry, which was the only cruciform one, was reportedly highly evaluated by the pope. It wasn’t popular with everyone, though, with architectural historian David Stewart stating, “the less said about Tokyo Cathedral, the better.” In 1970, Tange was awarded the Order of St. Gregory the Great for his design of the cathedral.

That same year, the Japan World Exposition, commonly referred to as Expo ’70, was held in Osaka. Tange and Uzo Nishiyama were appointed as the chief planners for the event, which proved a huge success. Other notable domestic structures created by Tange include the Shizuoka Press and Broadcasting Center in Ginza, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building, Shinjuku Park Tower and the Fuji Broadcasting Center, which is seen as a symbol of Odaiba.

Outside of Japan, Tange was probably most well known for his involvement in the reconstruction of Skopje — now the capital of North Macedonia, then part of Yugoslavia — after a major earthquake in 1963 destroyed 80% of the city. In Asia, he also designed the Supreme Court Building of Pakistan, the 68-story mixed-use Discovery Primea tower in the Philippines, the Singapore Indoor Stadium and some skyscrapers in Singapore that defined the skyline of the city’s central business district.

Kenzo Tange’s Death and Legacy

Kenzo Tange passed away aged 91 due to heart failure on March 22, 2005. He was widely considered the most influential figure in post-war Japanese architecture, inspiring several big names in the industry, including Kengo Kuma, the designer of the Japan National Stadium. “Kenzo Tange and the buildings he designed are one of the reasons why I became an architect,” said Kuma. “Above all, I think I was influenced by his method.”

As well as the Pritzker Prize, Tange received several other awards, such as the Royal Gold Medal in 1965 and the AIA Gold Medal the following year. An architect, teacher and urban planner, he was a visionary who led the Metabolism movement. The legendary designer once said, “There is a powerful need for symbolism, and that means the architecture must have something that appeals to the human heart.” And that’s exactly what his creations did and continue to do.