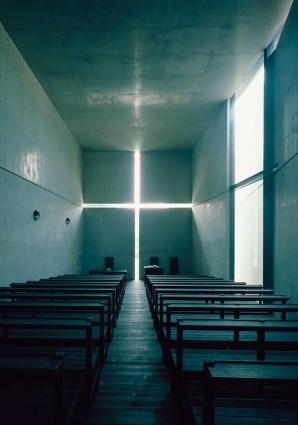

Minimalist, monochrome concrete buildings with a feeling of austerity: Tadao Ando’s designs may not sound too spectacular, yet in an understated, elegant way that is exactly what they are. Heavily influenced by Zen philosophy, the renowned autodidact architect puts his heart and soul into every project he’s involved in. From his Church of Light in Osaka to the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth in Texas, his work can be truly awe-inspiring.

A Pritzker Prize winner known throughout the world, Tadao Ando is a master of his profession. The fact that he is self-taught makes his rise all the more impressive. So how did this former boxer with no formal training in his field go on to become one of the leading figures in architecture? Weekender recently spoke with him to find out.

Can you start by telling us where your interest in architecture came from?

It started when I first witnessed my middle school math instructor teaching with a real passion. I began wondering about this subject, thinking there must be something special about it in order for him to teach so vigorously.

A few years later I watched as carpenters built a second floor to my house. Again it was their passion that intrigued me: they worked so hard every day that sometimes they would forget to eat their lunch. It was a similar feeling to the one I had before; I began thinking that there must be something special and interesting in carpentry.

I then connected the two dots and that is when I started showing an interest in architecture.

Yet you didn’t get into architecture right away…

No, I was a professional boxer in my late teens. I decided to do boxing because you get to fight and make money at the same time; I thought it was a great deal. My record was pretty good; however, I soon realized that I would never be the best in the world so I quit right then.

I may not have pursued boxing but I learned a lot and was able to train myself. Fighting in the ring, you are all on your own—nobody will help you and we can relate that to everything in life.

You then embarked on a world tour. How much of an impact did that have on your work?

I was in my early 20s when I traveled for eight months to see global architecture across Russia and through Europe, Africa and southern Asia before making my way back to Osaka. I didn’t have much money, so people often told me it was a life and death commitment to take such a trip, especially in those days. This intensive traveling period gave me a different perspective and allowed me to think in ways that I never had before.

I was particularly amazed by the scale of the Parthenon in Greece and the Pantheon in Rome. Le Corbusier’s church in Ronchamp was also very inspiring, presenting a space where architecture played a key role in gathering people together. Unfortunately, I was unable to meet him since I arrived in Europe a few months after he passed away.

My interest in Le Corbusier began in my late teens. I remember constantly tracing over his drawings. I discovered his book at a secondhand store and was instantly drawn to his pictures and architecture. Not having enough money to purchase it, I decided to hide it at the bottom of the pile so nobody would buy it, yet every time I went back to the shop the book was on top of the pile ready to be sold.

What were your thoughts on Japanese architecture at that time?

I have always been very impressed by traditional Japanese architecture. I very much appreciate the delicacy of Sukiya and Japanese tea houses. I am also amazed by the scale and power of traditional structures such as Itsukushima Shrine, Todaiji Temple and many others.

I think you can see good architecture scattered all over the country; this is a result of Japan’s rapid development after the war that ended in 1945. The problem is that there is a lack of unity throughout cities such as Tokyo. I believe it is crucial to somehow connect the different points to bring together not only the urban fabric, but also Japanese society as a whole.

You sound like someone who has spent years studying architecture, yet you never received any formal education in the subject. Did this make it more difficult to get started in the industry?

Yes, it was a big disadvantage for me as it was difficult to gain trust from people in those early years. I also did not have any classmates or professors to talk with about architecture. The amount of information I was able to collect was very limited. Having said all that, I wasn’t affected by trends or by what people thought; consequently it made it easier for me to develop my own language and methods of thinking.

What are your thoughts on modern trends in architecture?

I wouldn’t say it’s a trend, but the current generation has been heavily influenced by technology. This has enabled people, especially those in the design world, to achieve things that weren’t possible before. Therefore, I see technology as a great tool that can help develop new ideas and take us to a new sphere—that said, I hope we won’t let it take over.

I truly believe that people have to [create architecture] on their own, with their own physical body, because at the end of the day architecture is something that exists in the real world and not in the virtual one. Buildings need that human touch.

Would you say the way you incorporate nature into your work demonstrates that human touch?

Yes, for me the surrounding environment is very important. When I’m not satisfied with it I start planting small trees and try to make the area greener before the project begins so it will be ready when the structure is completed. For example, when I started Omotesando Hills my first concept was not to exceed the height of the nearby trees out of respect for the natural surroundings.

Also for me, just because the building is built doesn’t mean it’s completed. We as architects must take care of our buildings and nurture them. For many of my completed projects, I go on to do maintenance work ensuring that the structures are compatible with nature. I’ve been working on projects, such as the Rokko Housing complex and the museums in Naoshima [and other locations], for 25 to 30 years.

Do you feel any extra pressure when working on huge projects such as Tokyo Skytree or the Punta Della Dogana?

Every project is challenging in its own way and that is very exciting. I put an equal amount of effort into each one I’m involved in, even if some take longer than others. In order to produce something special I need to see some passion from the client: that is how I choose my projects. It has nothing to do with the site, program or budget.

Speaking of passion, how did you get to know Bono?

I have known him for quite some time. One day he walked in to our studio in Osaka and I was like, “who is this guy?” We went to Church of the Light together and he started singing “Amazing Grace” which was, pardon the pun, quite amazing. Ever since, we’ve kept in touch and whenever we are near each other anywhere around the world, especially in Europe, we catch up.

Finally, what advice would you give to any budding architects out there?

Face the world, keep looking for new challenges and no matter how things turn out, try to always move forward. Also—once again—going back to that word: passion. It’s so important to have passion if you want to create something special.

Main Image: Chichu Art Museum, room housing Walter De Maria’s Time/Timeless/No Time © Mitsuo Matsuoka

Tadao Ando, architecture, Pritzer Prize, Church of the Light