“It’s not something that came with the title,” says Stephanie Crohin, Japan’s first sento ambassador. “I was already doing all these things out of my own volition.” Crohin is referring to her passion for Japan’s bathing culture and all the promoting, writing and photographing she’s been doing on the subject for the past few years.

After arriving in Japan in 2008 on an exchange program with Rikkyo University in Ikebukuro, she had her first sento experience and her passion for the culture quickly grew. A decade later and she’s been named an official bathhouse ambassador by the National Sento Association, which means that now her daily life is even more packed with sento-related activities, from guest appearances on radio shows to giving private tours to first-time sento goers.

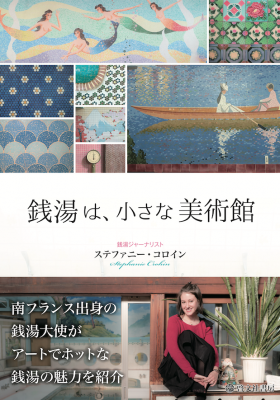

She often collaborates with different municipalities where she has the unique job of immortalizing and preserving the age-old culture of communal bathing in Japan. Her work has led to her publishing two books (in Japanese) in which she introduces beautiful bathhouses, interviewing the owners and photographing the facilities and artwork herself. Cumulatively, the books document over 100 bathhouses in Japan. Crohin, however, has visited over 800. It’s safe to say she’s an expert in the field.

“People always ask me the difference between sento and onsen. For me, the two words aren’t different or opposite from one another”

“People always ask me the difference between sento and onsen. For me, the two words aren’t different or opposite from one another,” she says. Both onsen and sento draw their water from underground sources, but the key difference is that onsen water contains a specific mineral or chemical composition. It’s undeniable that the word onsen carries significantly more weight than sento – the former certainly conveys an image of being more luxurious. Onsen, says Crohin, is a title that needs to be earned. The water must be tested and often the process isn’t cheap.

Interestingly, Crohin points out that many of Tokyo’s sento do draw their water from geothermic sources and have properties comparable to those of onsen, however, “some sento owners simply aren’t interested in that. There’s the price, of course, but more so they don’t want to attract people just for that.” Because there’s more to sento than just bathing.

Chuo-onsen, Takada, Nara Prefecture

Besides offering a place to wash one’s body, the sento is also a place to cleanse one’s mind. There are many benefits to frequent sento bathing, and as somebody who takes a dip up to five times a week, Crohin has had plenty of time to confirm this. Being at the sento means you are solely focusing on your own body with no outside distractions – no social media or text messages to snap you out of your bubble. And as you might expect, soaking in steaming, mineral-rich water has positive effects on your skin, too.

Mind and body benefits aside, Crohin reveals that what she came to appreciate the most was the community aspect of it. “This warmth that not only came from the baths but also from the people.” Crohin insists that a simple konnichiwa will attract friendly smiles, explaining that Japanese bathhouses are of course a place to wash your body, but they most importantly take on the role of neighborhood hub. “If you ever need to know what’s going on [in the neighborhood], you call the sento, because they will know,” she says, laughing.

Sento are also home to awe-inspiring murals. Called penki-e in Japanese, these works of art incorporate painting, ceramics and sometimes tiling. To paint these beautiful murals requires special training, as is the case for many traditional Japanese arts. There are currently only three professionals qualified to do this in Japan, with the youngest (and only woman) being 35-year-old Mizuki Tanaka.

Matsu no yu, Nishi-Waseda

Hotta-yu Nisharai

In Tokyo sento, you’ll often encounter depictions of Mount Fuji, but occasionally you’ll find fantastical mermaids or lush forests. “I went to a sento once and they had a mosaic mural of a Renoir painting,” says Crohin. “When I asked the owner why, he simply responded with, ‘My mother loved the painting, so she asked a painter if he could reproduce it.’”

Most countries follow certain practices when it comes to bathing, but Japanese sento are very particular when it comes to what you can and cannot do, and this might be daunting for first-timers. “It’s normal to make some mistakes,” says Crohin. “But it’s important to observe others and look at what they’re doing.” And to those who think it’s too embarrassing to be naked in front of strangers or even friends, she offers this encouragement: “Of course it’s weird for like the first five minutes. But you get used to it fairly quickly and you realize that nobody’s actually looking at you.”

I notice a small tattoo on Crohin’s wrist and ask if it has ever caused her any trouble, since most people are under the impression that sento do not allow people with tattoos to enter the baths. “It’s one of the biggest misconceptions out there,” she says, laughing. “In all the sento I’ve visited, only three were uncomfortable with my tattoos.” After all, the sento has always been a place where economical class and age doesn’t matter – and where social class matters less.”

Contrary to popular belief, sento aren’t public establishments. While it’s correct to say they’re spaces that are shared by a community, sento are privately owned facilities. Traditionally, they were a way for rich families or community members to give back to their neighbors. When more and more people started to go to these baths, rules were established and respected from sento to sento, but the buildings themselves remained private property. In other words, the only thing that’s public about sento are the rules that need to be adopted in order to join the National Sento Association.

Akebono-yu, Adachi

Kur Palace, Funabashi

Unfortunately, the number of sento in Tokyo has been steadily declining since the 1970s. Today, we count only about 530, a small number in a city with an estimated population of 13.4 million residents. The reason is partly because modern Japanese homes now have private bathrooms, but it’s also a result of demand for real estate. Sento are being demolished to make space for apartment complexes. These two factors are also causing the image of sento to change, moving from being viewed as a necessary establishment to a place that “stinks of old” in the eyes of younger generations – which is why Crohin’s work, which is shining a light on the modernity of sento, is important.

“I push people to try them as much as I can,” says Crohin. After their first experience, and after becoming comfortable being naked around others, most people begin to love sento. In metropolitan Tokyo, the sento is one of those rare places where you can experience Japanese tradition in its purest form, along with a true sense of community that transcends cultural barriers.

For more information about Stephanie Crohin’s work and her two books, “Sentos: Small Museums” and “A French Girl’s Guide to Sento,” visit dokodemosento.com and instagram.com/_stephaniemelanie_

Photographs by Stephanie Crohin