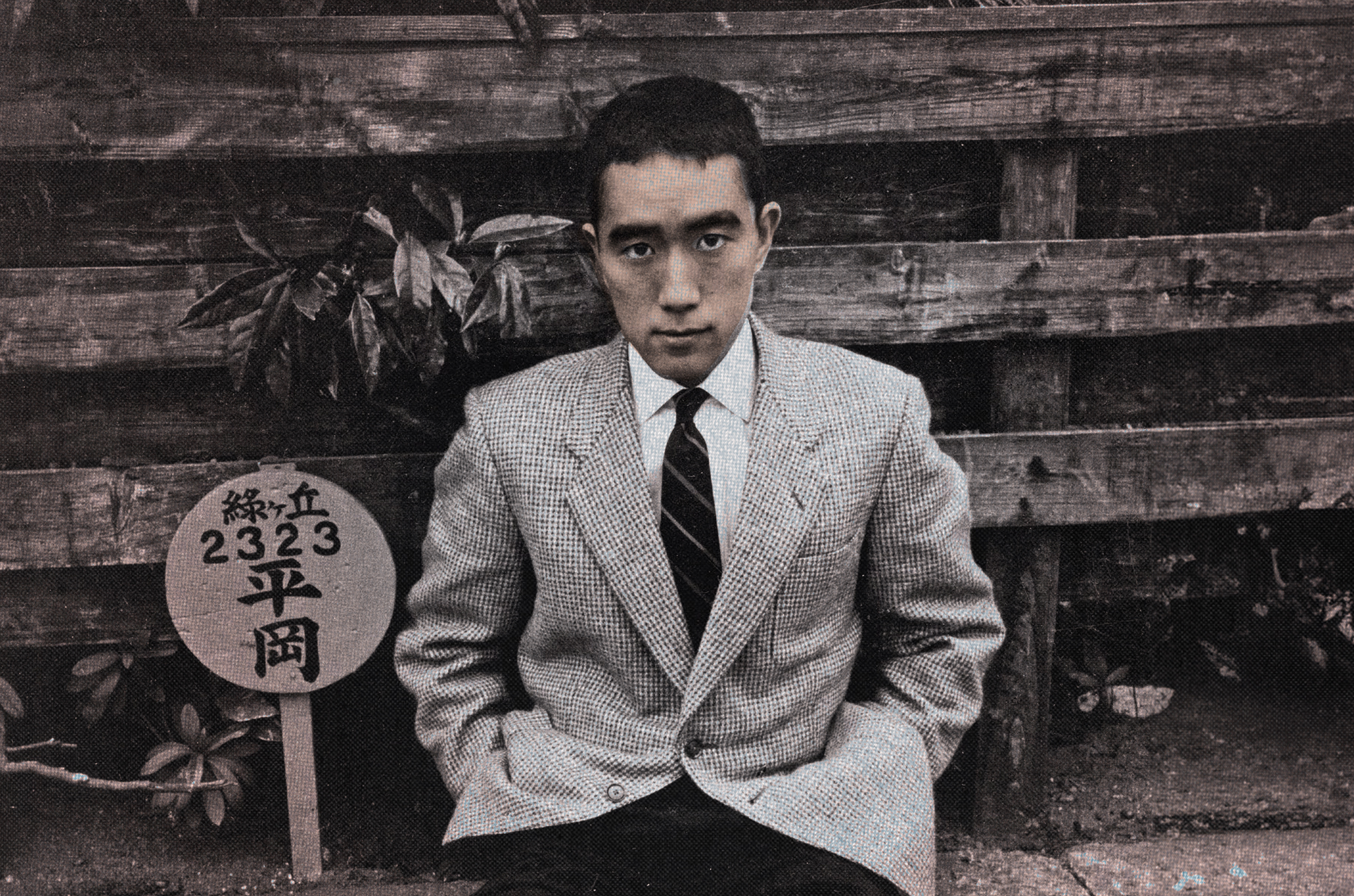

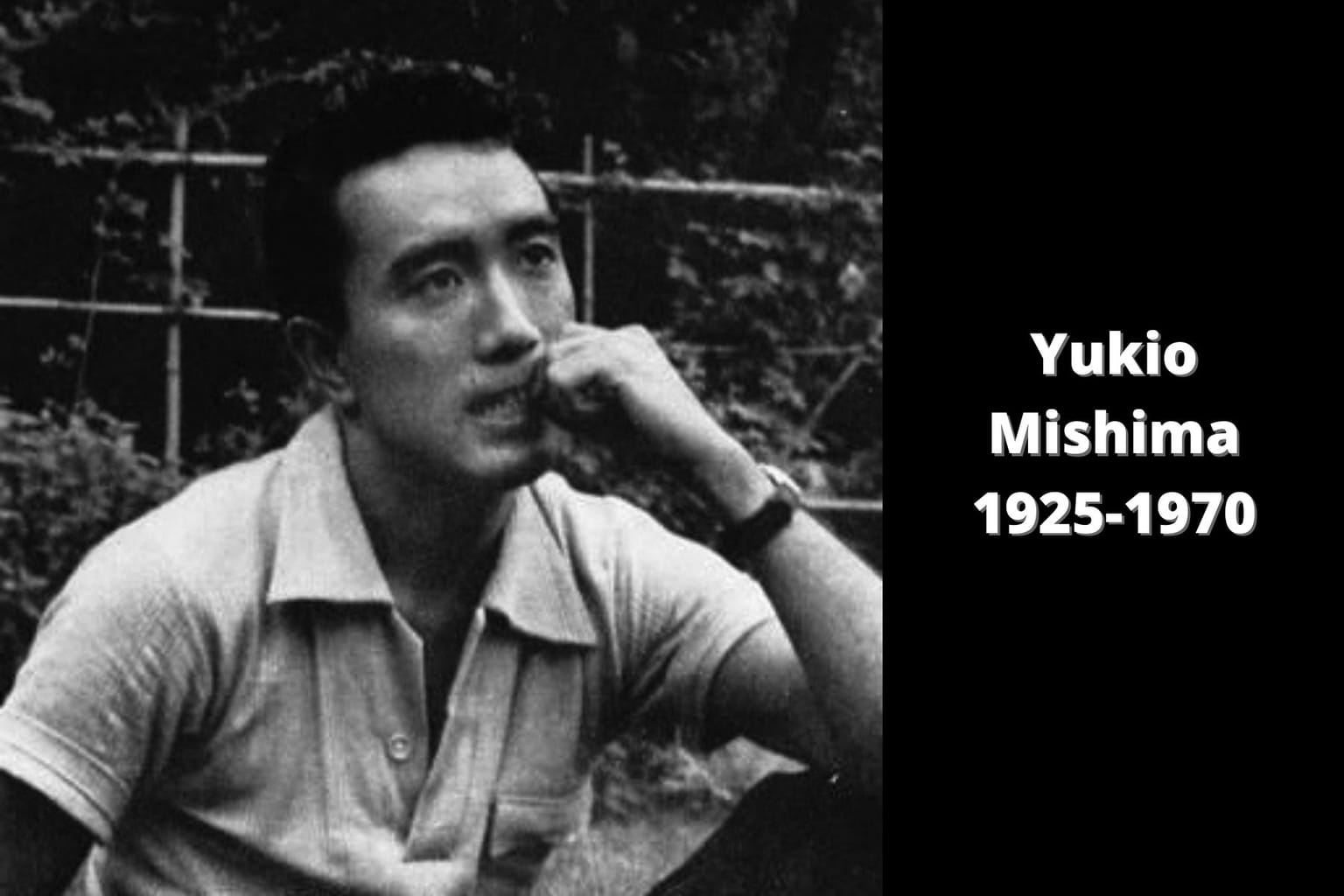

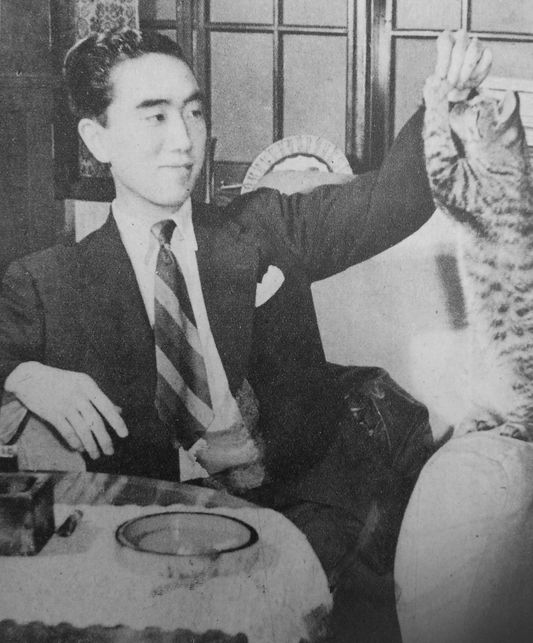

On this day a century ago, Kimitake Hiraoka was born in Tokyo. Better known by his nom de plume of Yukio Mishima, he became one of Japan’s most revered and prolific authors thanks to novels such as Confessions of a Mask, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion and The Sea of Fertility tetralogy. He was also one of the country’s most controversial figures due to his far-right ideology, which prompted his failed coup d’état and subsequent suicide by seppuku in 1970.

On what would have been his 100th birthday, we’re looking back at the life and times of the renowned author, poet, playwright, actor, model and ultranationalist for our latest Spotlight article.

Kimitake Hiraoka’s Background

Born into a traditional samurai family, Kimitake spent his early years in the care of his paternal grandmother, Natsuko. An enigmatic yet overbearing figure who was prone to violent outbursts, she separated Kimitake from his parents within weeks of his birth and forced him to live a very sheltered life. He wasn’t allowed to play sports with other boys or go outside in the sun. He spent much of his time either alone or playing with his female cousins.

The delicate and sensitive Kimitake was returned to his parents at the age of 12. His father, Azusa, who felt his grandmother had been too soft on him, favored military-style discipline, discouraging anything he deemed effeminate. In an attempt to scare some masculinity into his son, Azusa even held the young Kimitake up to the side of a speeding train. He also ripped up his manuscripts. The youngster was forbidden from writing any other stories but continued to do so in secret, with encouragement from his mother.

At the age of 16, Kimitake penned the short story Forest in Full Bloom about a deep connection he felt with his ancestors. His teacher, Fumio Shimizu, was so impressed, he pushed for the story to be featured in the national magazine Bungei Bunka. The editorial board agreed to include it. The only problem was the potential backlash from the teenager’s father. Shimizu subsequently gave him the pen name Yukio Mishima (“Yukio” from the Japanese word for “snow” and Mishima from the name of a train station Bungei Bunka board members passed through on the way to their meeting with him).

Yasunari Kawabata

World War II and Confessions of a Mask

In 1944, three years after Forest in Full Bloom was published, Kimitake — henceforth referred to as Mishima — graduated from Gakushuin High School, which was initially established to educate the children of Japan’s nobility. Emperor Hirohito attended his graduation ceremony. That same year, Mishima received a draft notice for the Imperial Japanese Army. However, misdiagnosed as having tuberculosis, he was declared unfit for service. He always regretted not dying for his emperor.

After the war, Yasunari Kawabata — who would go on to become Japan’s first author to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature — became Mishima’s mentor. He later described his protege as the kind of genius who comes along every 300 years. Mishima himself was reportedly considered for the Nobel Prize on several occasions but never won the award. Despite this, he was regarded by many critics as the most important Japanese novelist of the 20th century.

His first full-length novel, Thieves, about two young members of the aristocracy drawn to suicide, was published in 1948. It was his second book, though, that launched him into national fame. Widely seen as semi-autobiographical, Confessions of a Mask tells the story of a tormented adolescent named Konchan who finds it difficult to fit into Japanese society after being kept away from boys his own age. He wears a metaphorical mask to present his false personality to the world and hide his homosexuality.

Michiko Shoda while playing piano in October 1958. Mainichi Shimbun photo. Public Domain

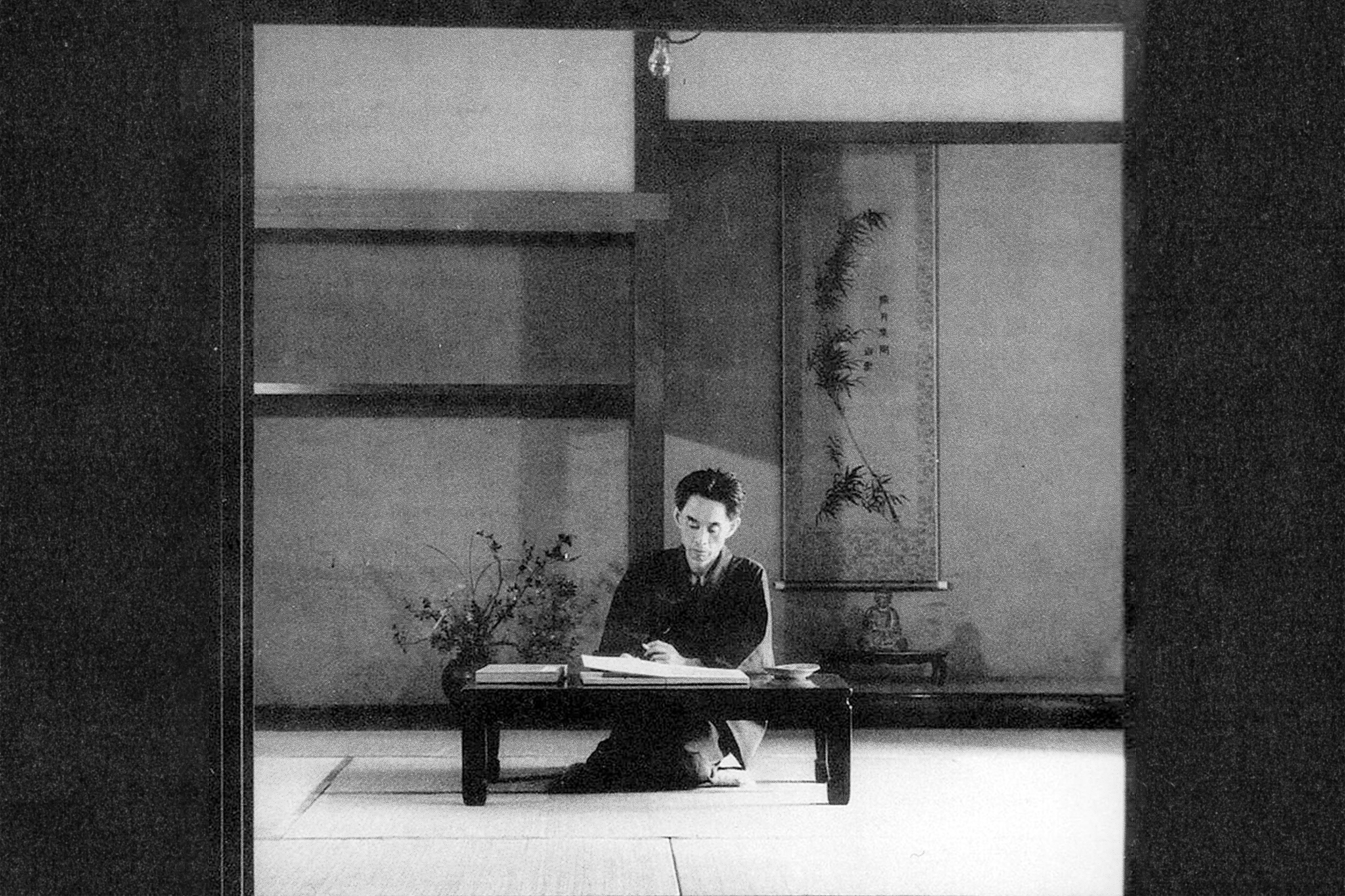

More Than Just a Writer

After the success of Confessions of a Mask, Mishima continued to enhance his reputation in the 1950s with novels such as The Sound of Waves, a coming-of-age story about a young fisherman who falls in love with the daughter of the wealthiest man in the village, and The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, which was loosely based on the destruction of Kyoto’s Kinkaku-ji Temple by a young Buddhist acolyte in 1950. He also wrote several noh and kabuki plays.

By the 1960s, Mishima was seen as a superstar in Japan. Away from writing, he worked as a model and actor, most famously appearing as the lead character, Takeo, in Yasuzo Masumura’s 1960 yakuza film, Afraid to Die. Known for his muscular upper body, he often portrayed strong characters in movies, reflecting the image he wanted to paint of himself. This desire to be seen as robust had roots in his youth, when Mishima had struggled with insecurity related to his short stature and limited physicality. To combat these feelings, he took up bodybuilding in his early 30s.

This pursuit of his ideal physique was a top priority, and the obligation to avoid disrupting his weight training was, along with a prohibition on interfering with his writing, part of Mishima’s prenuptial demands for any potential wife. These orders may have been what put Michiko Shoda, the future Empress Michiko (and current empress emerita) off from marrying him. According to several of his biographers, Mishima pursued the future empress, who, in 1959, became the first commoner to marry into the Japanese Imperial Family. A year before those historic nuptials, Mishima tied the knot with Yoko Sugiyama, daughter of famed painter Yasushi Sugiyama. Though they had two children together, rumors about his sexuality persisted long after he died.

Approaching the Final Act

In 1963, Mishima released one of his most popular novels and a personal favorite of David Bowie, The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea, about a group of savage 13-year-old boys in a story that’s reminiscent of William Golding’s The Lord of the Flies. Two years later, he published the critically acclaimed historical fiction play Madame de Sade, based on the life of the Marquis de Sade’s wife, Renée de Sade. That same year, the literary magazine Shincho began to serialize Spring Snow, the first book in Mishima’s tetralogy, The Sea of Fertility.

Spring Snow was followed by Runaway Horses and The Temple of Dawn. The manuscript for The Decay of the Angel, the fourth and final part of what is considered Mishima’s magnum opus, was then left for his publisher, Shinchosha, in a fat envelope on a desk at his Western-style home on November 25, 1970. Alongside it was a note that read, “Human life is limited, but I would like to live forever.” A few hours later, he was dead. His attempted coup failed, and as a result, he disemboweled himself with his sword.

In the decade leading up to his shocking ritual suicide, Mishima’s far-right ideology became increasingly evident. Biographers and scholars agree that the Anpo Protests against the United States-Japan Security Treaty 10 years earlier marked a major turning point in his career. According to Nick Kapur, author of Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo, the protests “awakened in Mishima an understanding of the power of the spectacle, and this understanding would be a guiding force in his future writing and public behavior in the ensuing decade leading up to his spectacular death.”

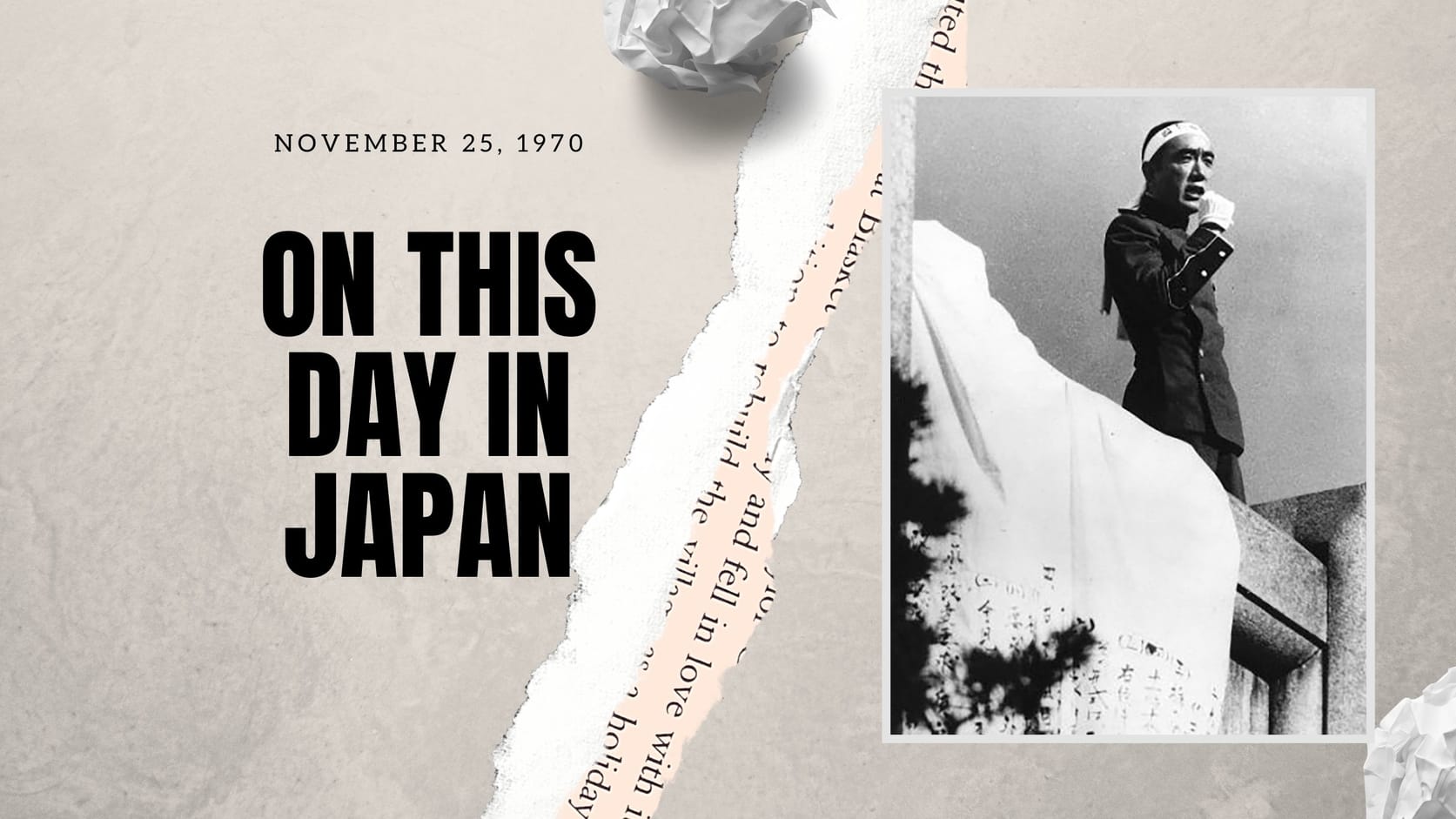

The Death of Yukio Mishima

In 1968, Mishima established the Tatenokai (Shield Society), a small private army consisting mostly of university students who vowed to protect their “living god” emperor. Two years later, four members of the group who had displayed unswerving loyalty to their leader were handpicked to assist the playwright with his final act. Ostensibly, the goal was to get inside the Eastern Headquarters of the Ground Self-Defense Forces so Mishima could persuade them to join his militia in a coup against the government to overturn the 1947 constitution. However, many — including one of his biographers, John Nathan — believe his intention all along had been ritual suicide.

After tying General Kanetoshi Mashita to a chair, Mishima stepped out to the balcony to address the soldiers. Decrying their passive acceptance of the constitution, he asked: “Where has the spirit of the samurai gone?” This just irritated the crowd as they heckled and booed him. The speech, which was supposed to be 30 minutes, finished within seven with the words “Long live the emperor.” Going inside, he apologized to the commandant before disemboweling himself with his sword. It was the first act of seppuku since World War II.

Masakatsu Morita, rumored to be Mishima’s lover, was unable to complete his role as kaishakunin (the person appointed to behead an individual who has performed seppuku), so fellow Tatenokai member Hiroyasu Koga took over. Morita then stabbed himself in the abdomen before being decapitated by Koga. It was a bloody mess that stunned the nation. Some saw Mishima’s attempted coup and subsequent suicide as a patriotic statement against the growing Westernization of Japan. Others felt it was a pointless act by a narcissistic madman, who, in the words of Prime Minister Eisaku Sato, “went out of his mind.”

More From This Series

- Miki Matsubara: A City Pop Icon

- Sonny Chiba — A Martial Arts Legend

- The Faces of Japan’s New Banknotes

Updated On January 15, 2025