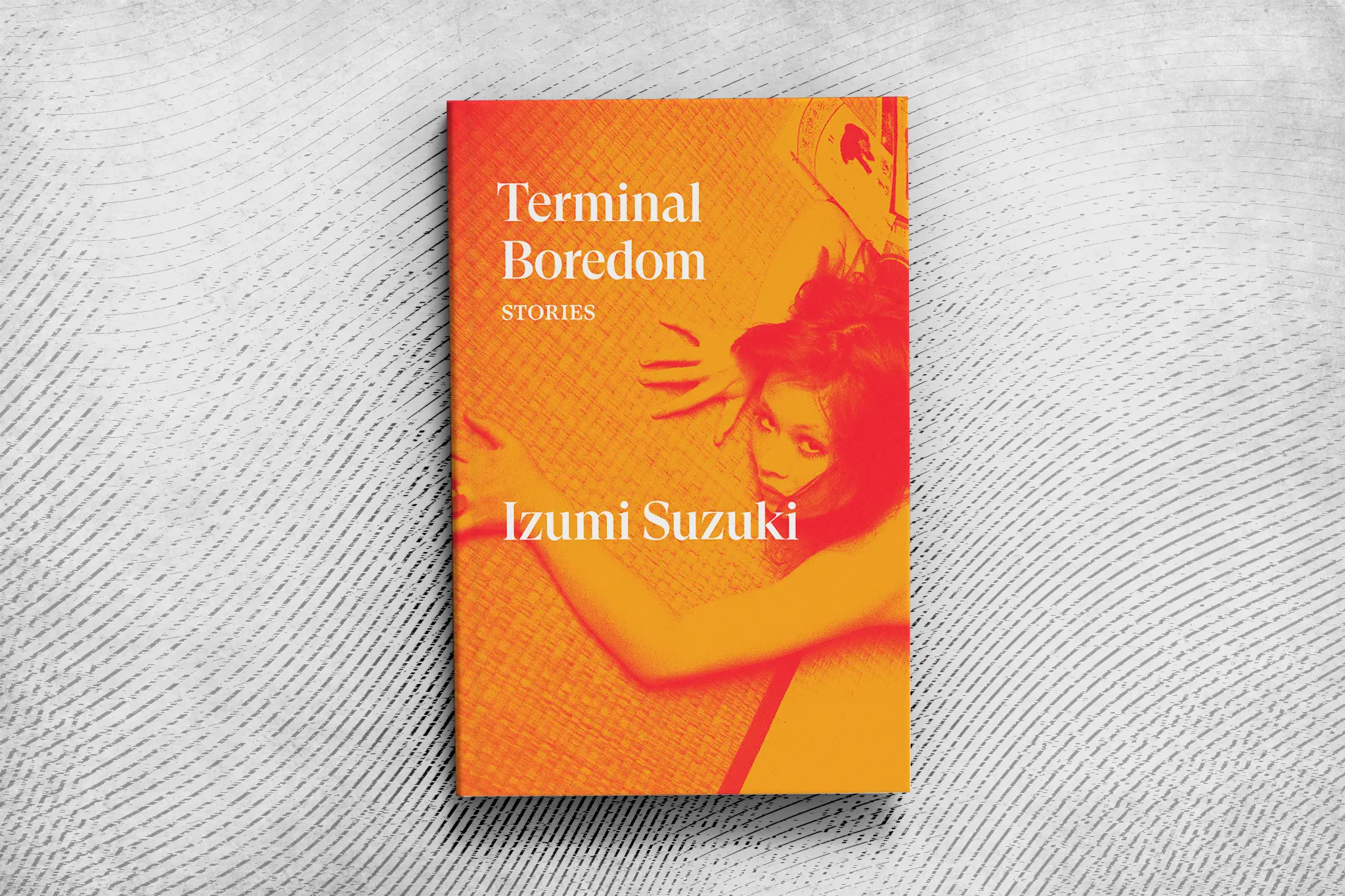

A legend of science fiction, Izumi Suzuki holds cult status in Japan. However, her introduction to the Anglophone literary landscape was incidental: an editor at Verso Books saw her name mentioned in a footnote to an academic thesis and wanted to know more, but the lack of information about Suzuki in English complicated an easy conveyance from east to west. After months of painstaking research and translation, Terminal Boredom was published by Verso Books in 2021. This collection of short stories offered English-speaking, 21st-century readers access to Suzuki’s other-worldly Japan for the very first time. Her work was praised for her “punky” style and “pitch-black” approach to issues that remain relevant in contemporary society.

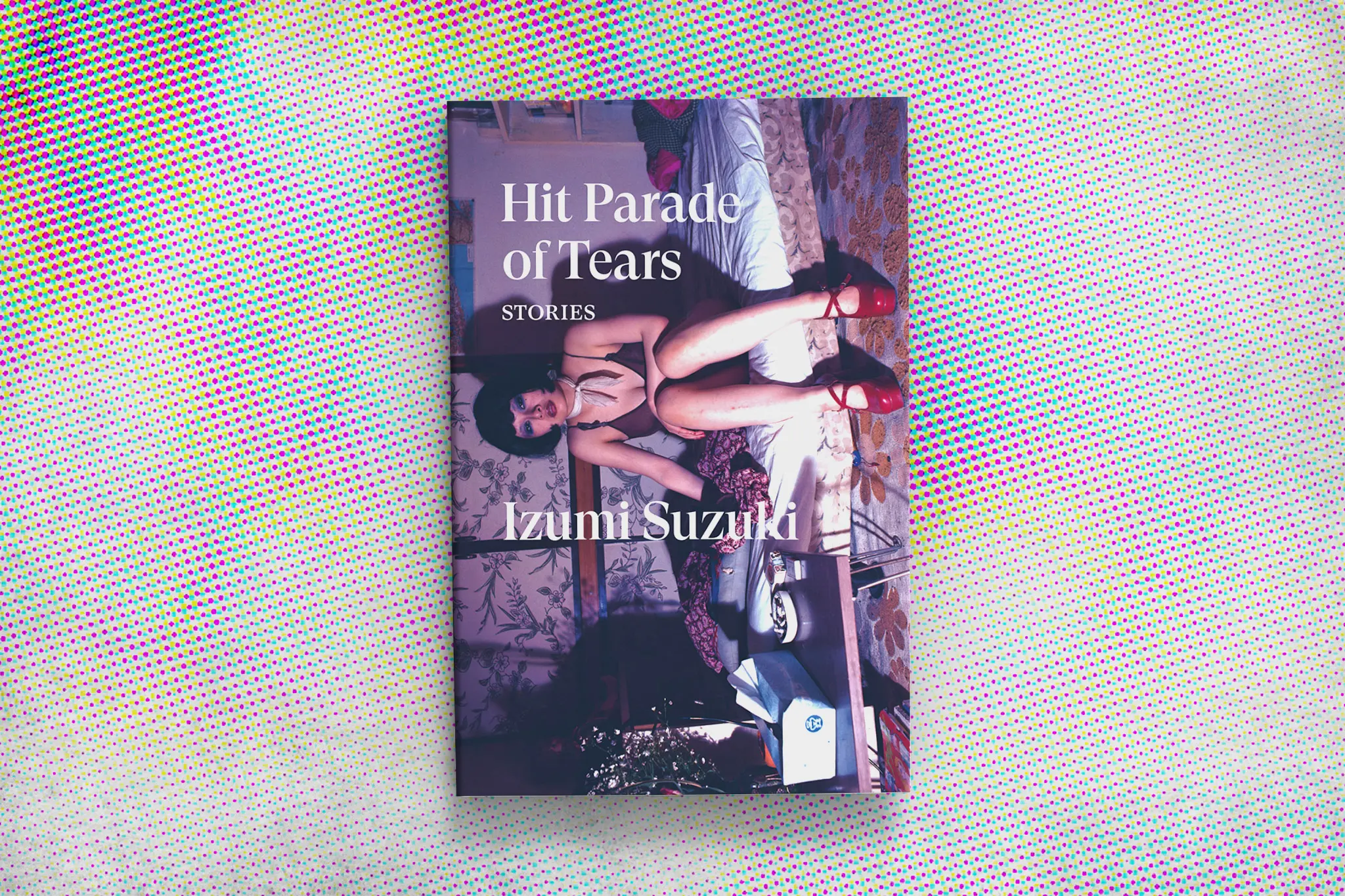

Suzuki readers are eagerly anticipating the publication of a second collection, Hit Parade of Tears, to be released by Verso Books in April of this year. Despite her long overdue introduction to the English-speaking world, Suzuki’s writing still packs a punch, and you would be forgiven for thinking these stories were written today. It is this sustained pertinence that makes her such an intriguing figure.

A Brief Look Into Izumi Suzuki’s Life

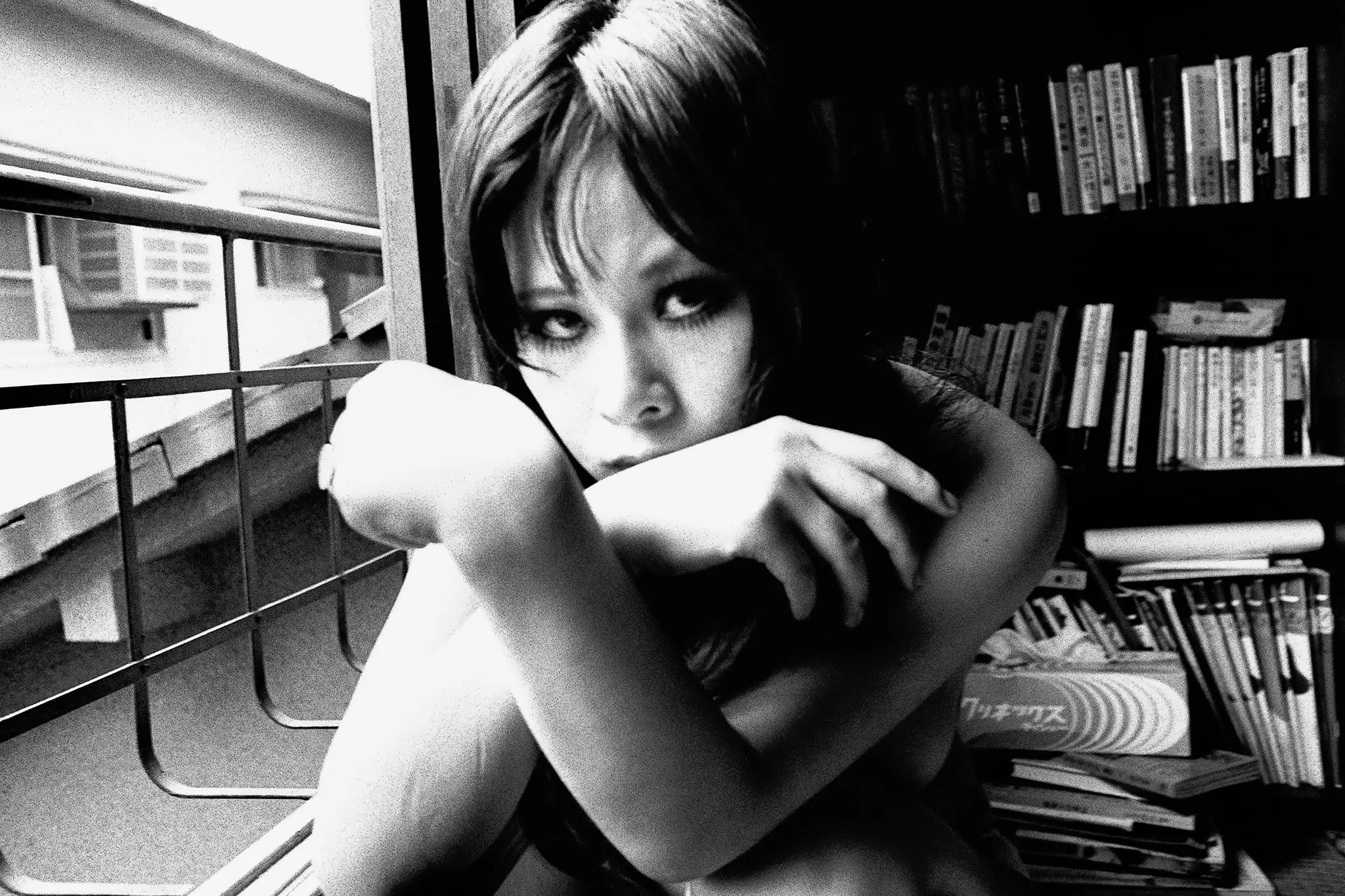

Suzuki was born in 1949 in Ito, Shizuoka prefecture, at the brink of a decidedly important time in Japan’s cultural history. The post-war landscape saw a rise in counter-cultural art and expression accompanied by considerable anti-establishment sentiment. Suzuki’s own life was fittingly unorthodox. She initially found acting work in pink films. She was also a member of an avant-garde acting troupe and, throughout her career, modeled for photographer Nobuyoshi Araki, a prolific Japanese artist known for his erotic, sometimes even pornographic photography.

Deeply intrigued by the American culture that infiltrated Japan by way of military occupation, she spent much of her 20s in areas such as Honmoku and Yokosuka, unearthing the latest bands and films by way of the American-imported jukeboxes that offered portals to far-away worlds. She had a brief, tumultuous marriage with avant-garde saxophonist Kaoru Abe, with whom she had one daughter. Abe died from an overdose in 1978, aged 29. Suzuki took her own life eight years later, aged 36.

Izumi Suzuki’s Place in Japanese Sci-Fi

Japanese science fiction had its heyday in the 1980s. In a generic boom mirroring the rise in interest in the Western world, by 1980 there were more than 40 sci-fi publications in circulation in Japan. Suzuki, however, was never permitted to join the SF Writers Club made up of her male peers. She, along with other female writers of the era, were treated as “tourists” to the community. However, despite the gendered grounds on which Suzuki was excluded from the canon, it seems fitting to consider her writing in its own category. While both of her collections may be populated by aliens, Suzuki’s science fiction is distinct from that of her male contemporaries.

Translator Helen O’Horan describes her writing as “psychedelic science fiction.” She believes the expansion of consciousness prompted by the genre allows Suzuki to “voice the associations that seem to connect in your head.” As O’Horan sees it, the guise of science fiction allows Suzuki to describe what she’s thinking and feeling, and “get away with it.” She deals in inconsistency, doing away with pre-defined templates and ideas ordinarily imposed upon earthlings.

While it is yet to be translated into English, Suzuki also wrote a great deal of realist literature over the course of her short, yet prolific career. Identifying the strong parallels between the two fictional modes, O’Horan instead sits Suzuki’s work along a generic spectrum, suggesting that “when [Suzuki] herself is writing, there isn’t really the same distinction created.”

The same turns of phrase are used to describe aliens and humans, some passages are even lifted verbatim. In “Memory of Water,” one of the stories from the latest collection, also translated by O’Horan, Suzuki’s protagonist — who we assume to be human — reflects that “there wasn’t anywhere in this world where she did feel comfortable.”

In the various worlds that Suzuki creates, it is not only extra-terrestrial creatures who feel they are masquerading as humans. As fellow translator Daniel Joseph concludes: “for Suzuki, the everyday is science fiction.”

Alienating Gender

This speculative approach to the human condition similarly informs Suzuki’s formulation of gender. While much of the writing invites consideration of what readers today might refer to as “feminist issues,” O’Horan suggests that Suzuki “doesn’t really identify with the idea of essentially being a woman.” She is untethered from Western conceptions of gender politics both temporally and geographically. Gender roles are tried on and discarded like costumes, made alien in the jagged and uncanny landscapes of the tales.

“Women and Women,” the opening story to Terminal Boredom, is set in a men-less matriarchy. It’s a seemingly utopic society where men — “utterly unmanageable creatures” — are imprisoned to protect social order. However, when Suzuki’s protagonist befriends a fugitive young boy, who camouflages himself in women’s clothing to avoid the Gender Exclusion Terminal Occupancy Zone, she begins to wonder whether there isn’t “something off about this society.” The overly defined binary of socialized gender roles is thrown into farcical relief. There is a drag-like quality to Suzuki’s writing and the relevance of her work in today’s society speaks for itself, even while resisting easy assimilation into contemporary discourse.

Despite the shifting cultural landscape that was unfolding around her, Suzuki creates worlds subtly unstuck from specific times and locations. It is because of this dislocation that her writing still speaks to readers today. In a constant tussle with the familiar and unfamiliar, Suzuki’s stories are underwritten with uneasy introspection: encounters with alien creatures and lands hold the mirror back up to the reader, and we are forced to reconsider what we have collectively agreed to be ‘normal.’ The anxiety at the heart of her writing resonates far beyond its temporal walls. Suzuki’s science fiction of the 1980s has an eerie accordance with the world as we know it today.