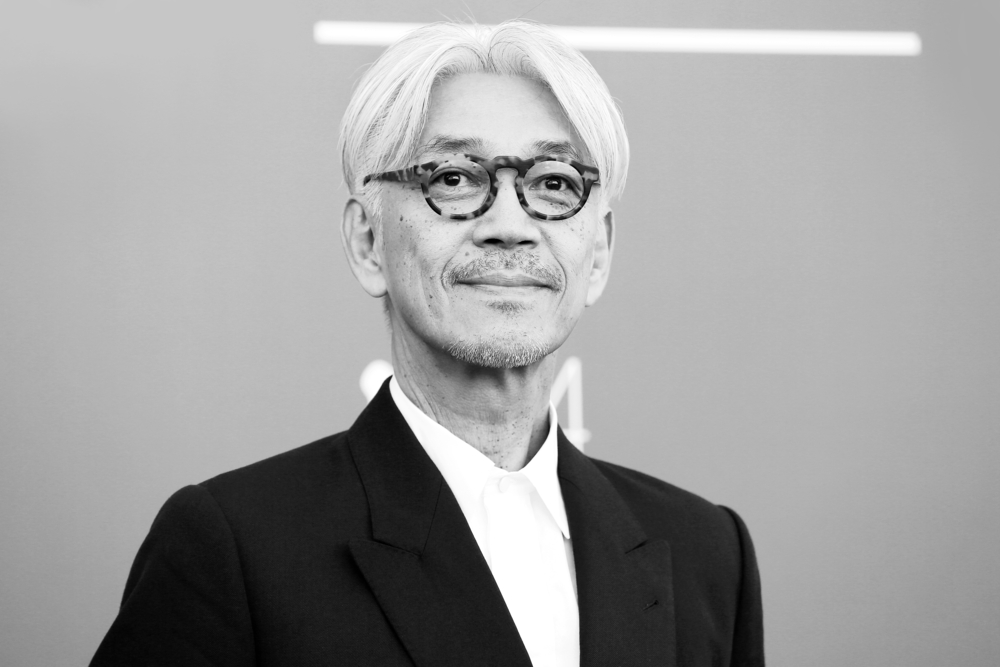

Ryuichi Sakamoto, the irreplaceable Japanese composer, musician and sound curator, who died on March 28 at the age of 71 and whose status as both genius and innovator seems more than assured, was an artist who well understood the ongoing cumulative and ultimately collaborative nature of human creativity. He also seemed at perfect ease with his place in that great conversation.

From his earliest days as a student at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music, through stints as a solo artist and session musician that led him to massive domestic and sizeable international fame alongside Haruomi Hosono and Yukihiro Takahashi as YMO (Yellow Magic Orchestra); through mid-life success as an in-demand and much celebrated soundtrack composer and into the final contemplative chapters of his life, Sakamoto not only made in-depth studies of what had come before him, but simultaneously learned from and influenced the present. Despite long periods working in relative seclusion, he wanted to do more than just leave lessons for those who would come after him. Until the end, he compared notes with and worked alongside both his contemporaries and younger artists.

YMO: Techno-Pop Pioneers

He was brought to YMO by Hosono, the oldest and now only surviving member of the band. His first contribution to the group, then known as Harry Hosono and The Yellow Magic Band, was on the cheerfully faux-tropical 1978 album, Paraiso. YMO enjoyed extraordinary success at home and abroad, becoming not only the introduction for many to the brave new world of techno-pop, but for fans overseas, a window to a stylish and modern Japan that may not have tallied with older preconceived notions of that venerable nation.

Although synthesizer music was by no means unknown in 1978, to mainstream audiences it may have conjured images of either novelty throwaway hits (such as Hot Butter’s “Popcorn”) or more serious listening music. Its links to classical music were well established by the works of Wendy Carlos and Japan’s own Isao Tomita. Comparable only to Düsseldorf’s po-faced pioneers Kraftwerk, who were having lots of fun but pretending not to, the sight of three snappily turned-out Tokyoites performing joyously addictive pop music from behind banks of impressive equipment did a huge amount of work in changing perceptions of synthesizer music and ushering in the innovations of 1980s pop and the electronic music that followed.

Photo by Andrea Raffin via Shutterstock

The Biggest Thing in Japan

From the very beginning, the music of YMO was inspired and informed by the kind of easy-listening exotica of artists such as Les Baxter and Martin Denny in a playfully arch attempt at bringing east-meets-west vicarious holiday music back towards the east it had at least notionally sprung from.

The band’s barnstorming circuit-fizzing cover of Denny’s “Firecracker” proved hugely influential. Especially in the US. It was sampled by Afrika Bambaataa and De La Soul as well as Mariah Carey and Jennifer Lopez, who allegedly fell out over who was the first to do so.

Sakamoto was already exploring similar ideas on his first solo LP, Thousand Knives, released one month before YMO’s self-titled debut. In an introduction to some of the themes that would be explored throughout his career, the album took variations on Chinese and Japanese melodies, western and jazz harmonies, synthesizers and pianos. It combined them into a sometimes knowingly kitsch but heady and immersive blend of avant-garde fun.

By 1980, following the success of their domestic chart topping classic Solid State Survivor, YMO were the biggest thing in Japan. Sakamoto, who did not particularly enjoy celebrity status, then released his second solo LP, the altogether more experimental B-2 Unit. It was recorded partly in London, and perhaps inspired by YMO’s 1979 visit to that city. While there, Sakamoto had been excited by what he saw as the transition period between punk and new wave and was thrilled by the “radical, fashionable young people on the streets and in the venues.”

B-2 Unit is made up of textural and tonal explorations of sound that seem to modern ears achingly prescient. Putting rhythm and atmosphere center stage and reveling in repetition and claustrophobic discordancy, the occasionally malevolent machine music of B-2 Unit was a crystal ball vision of the electronica and techno music that would make itself known to the world at the opposite end of the decade and in the early parts of the next. It’s often cited as a forerunner to early electro and hip-hop music. Mantronix, for instance, cite the Fela Kuti-inspired track “Riot in Lagos,” with its rumbling bass, skittering rhythms and chirruping misdialed micro melodies, as a strong influence on their music. The album also became something of an underground club success. While its sound is still not mainstream today, it may prove to be one of Sakamoto’s most enduringly influential contributions to electronic music.

A Musical Soulmate

In the same year as recording B-2 Unit, Sakamoto lent his keyboard skills to androgynous English art-poppers Japan, playing on the song “Taking Islands in Africa” from their fourth album Gentlemen Take Polaroids. In frontman David Sylvian, Sakamoto seemed to find something of a musical soulmate. The two became frequent collaborators over the next three decades. The most famous track they did together was “Forbidden Colours,” in which Sylvian added plaintive vocals to Sakamoto’s pristine and elegiac theme tune to Nagisa Oshima’s powerful 1983 prisoner-of-war film, Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence. Sakamoto also took an affecting star turn in the movie before deciding that acting wasn’t for him.

In 1985, with YMO having discreetly called it a day, Sakamoto began work on his diverse and playful solo album Illustrated Musical Encyclopedia. He was also the subject of Elizabeth Lennard’s quirky and evocative portrait film Tokyo Melody: un Film sur Ryuichi Sakamoto. The seemingly self-conscious but charmingly amenable 32-year-old Sakamoto allowed himself to be seen as both a serious and hard-working studio musician, and in a series of lighthearted and semi-surreal skits, as a sort of stylish class clown figure.

Subjected to a not entirely comfortable interview and speaking directly to camera, he made the surprising and perhaps mischievous claim that he would never have studied classical music if he had heard The Beatles earlier. He then, however, went on to offer in response to an unheard question — which the viewer must presume was about his influences and inspirations — a list of indisputable 20th century avant-garde greats. This included composers such as John Cage, Maurice Ravel, Igor Stravinsky, Henri Dutilleux and Olivier Messiaen, as well as visual artists Andy Warhol and Marcel Duchamp. Study of this tasteful list not only offered precise brewing notes for Sakamoto’s perfect cup of cultural tea, but also turned the cup over to give viewers a reading of the leaves. It was a glimpse into what would come to pass in the four prolific decades that we now know Sakamoto had ahead of him.

Ryuichi Sakamoto

Musical Influences

Cage’s “4’33,’’” which was composed in 1952, the year of Sakamoto’s birth, held a lifelong fascination for him. The themes of silence (or more accurately, the impossibility of silence), space and the places where music and sound meet that are contained in the often unfairly derided piece were all essential elements of Sakamoto’s work. Their importance to him seemingly grew with age. From Ravel and Stravinsky there is, of course, beauty and a scene-setting ability to conjure images, but also a visionary willingness to go against the grain and shake things up where necessary. These were lessons learned and utilized by Sakamoto, not only in his body of stirring and evocative soundtrack work, but in his refusal to rest on his laurels and his dedication to forward momentum.

From Dutilleux and Messiaen we see the ability to combine complex and non-traditional — perhaps even non-musical — ideas into works with a challenging but undoubted modern sensuality. Messiaen’s fascination for and use of birdsong, in particular, again foreshadows Sakamoto’s later life interest in breaking down or blurring the barriers between sound and music. This playful yet serious openness to profound questions about the differences between consciously created art and everyday life — along with themes of repetition, replication and variation that are important to all musicians — are where Warhol and Duchamp came into Sakamoto’s fortune-telling mix.

These long-foreseen elements came together in the work of what we now know were Sakamoto’s final years. This included his abstract and thoughtful ambient collaborations with kindred spirits Alva Noto and Christian Fennesz, and are utilized perhaps most beautifully on his final two solo albums, 2017’s Async and 2023’s 12, released just two months before his death. It was Sakamoto’s chance to say a typically elegant goodbye.

Conspicuously absent from Sakamoto’s Tokyo Melody list, perhaps in a momentary attempt at keeping something back for himself, was Claude Debussy. He was Sakamoto’s self-declared hero and the man he called “the door to all 20th century music.” That Debussy’s intricately beautiful and often deceptively simple works were informed by non-European sound modes was not lost on Sakamoto, who speaking in 2010 stated, “Asian music heavily influenced Debussy, and Debussy heavily influenced me. So, the music goes around the world and comes full circle.”

This idea of a cross-cultural pollination and blooming of musical inspiration, as well as the important truth contained in the (possibly apocryphal, but entirely apt) Debussy quote, “Music is the space between the notes,” seeming as they do to offer a two-for-one introduction to Sakamoto’s own lifelong creative themes and obsessions, make it readily clear why he felt such affinity for this particular forebear and why the two men will almost certainly be talked about in the same breath across the unknown centuries to come.